Copyright cleveland.com

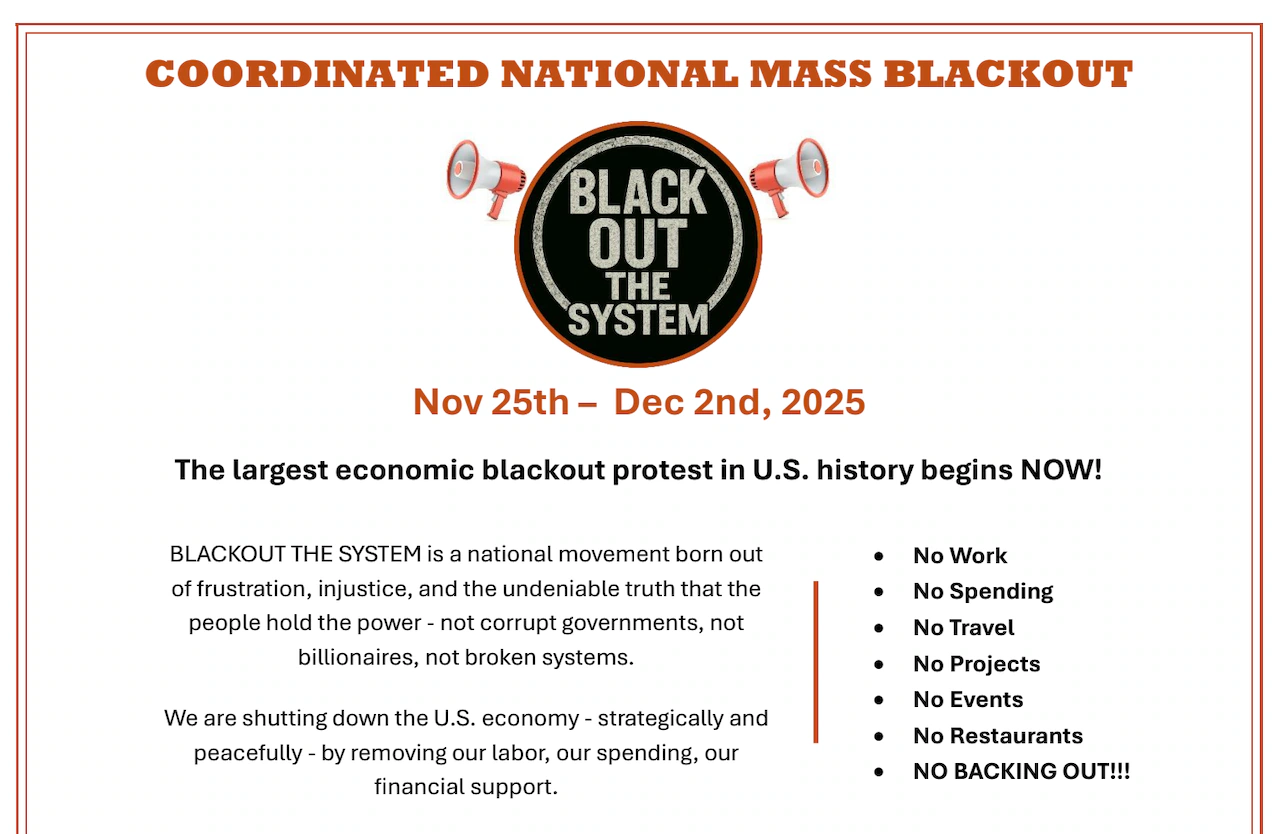

WASHINGTON - A grassroots movement calling for Americans to stop spending money from Nov. 25 through Dec. 2 is gaining traction on social media, with organizers hoping to pressure businesses and policymakers by targeting one of the busiest shopping periods of the year. The “Blackout the System” campaign, promoted by activist groups and celebrity supporters including actress and comedian Rosie O’Donnell, urges participants to avoid all purchases except from small, local businesses during the week-long “blackout” that would span Black Friday and Cyber Monday. Organizers frame the effort as a test of economic power rather than a traditional protest march, citing historical precedents like the Montgomery Bus Boycott as evidence that economic pressure can drive social change. The question is: Will it work? “From November 25 to December 2, the goal is simple, OK, buy nothing that doesn’t circulate back into us,” social media influencer Ashley B said in a video promoting the boycott that has been viewed more than 200,000 times on YouTube. “Support small, support local, support Black. Because when we withhold our dollars, we remind this country that we’re not just consumers, we are the economy.” The blackout campaign extends beyond just halting spending. According to the Blackout the System website, organizers are also calling on participants to refrain from working during the week-long period. The website lists “No Work” alongside “No Spending” and “No Travel” as key components of the action. “We are shutting down the U.S. economy - strategically and peacefully - by removing our labor, our spending, our financial support, forcing the system to listen,” the website states. The movement describes itself as using both consumer spending power and withdrawal of labor as leverage, “to bring the system down to its knees.” An affiliated website says the movement’s goal is to “build a new kind of economy. One that respects labor, distributes wealth fairly, and restores dignity.” O’Donnell promoted the blackout to her Instagram followers, while platforms including Black Enterprise and Shine My Crown have featured articles explaining the campaign’s goals. Isaiah Rucker, Jr., who founded Blackout the System, said in an email that the movement began with a social media post calling for people to “stand together and push back against corrupt government activity, corporate greed, and the lies we’ve been fed to divide us.” He described the initiative as promoting “unity across all races, cultures, and economic backgrounds to see justice, equality, and equity in our nation and the world.” He said it has partnered with other groups including The People’s Sick Day, The Big Beautiful Boycott, and The Progressive Network and received support from chapters of national organizations like 5050/1 and Indivisible. He said that after the No Kings 2.0 demonstrations in October, his organization has seen an increase in curiosity, engagement, and support. “We don’t have a left vs. right problem; we have a top vs. all the rest of us problem,” Rucker wrote, explaining that the movement aims to address wealth inequality and what he describes as corporate influence over elected officials. Rucker said organizers have “supporters in all 50 states” and “a strong base” in Ohio “who engages, interacts, and shares the movement across their networks,” though the movement does not have a specific organizer based in the state. The group conducted a previous action from September 16-20, which Rucker said reached “over 40 million viewers” across the movement’s social media pages and attracted participants from all 50 states and nearly 50 countries. He predicted “millions” will participate in the upcoming Mass Blackout. “Our goal is to help people understand that greed is the disease in this country,” said Rucker. “Organizations exploiting the people, forming PACS, purchasing politicians that we’ve elected, and those corrupt politicians are making policies that are detrimental to the people. It is important to us to help others identify the wealth inequality, exploitation, erosion of rights, engineered division, and the overarching truth that the system no longer prioritizes service to the people, but to corporations.” But Case Western Reserve University economist Jonathan Ernest says the strategy faces significant hurdles. Ernest, who teaches at the Weatherhead School of Management, said broad, short-term boycotts typically have limited economic impact. “If the boycotting group is seeking a clear, identifiable outcome or goal, and conducts a boycott targeted at a particular store or company, then that company may feel a large impact if the boycott can be maintained for a long period of time, or during times of heavy consumer traffic for the retailer,” Ernest said in an email. “On the other hand, general boycotts are typically less effective for a variety of reasons.” Ernest explained that single-day or week-long boycotts often result in “temporal spending shifts” rather than actual lost sales. “If you were going to purchase an item on the day of the boycott, you might just shop early or delay your purchase until after the boycott rather than forego the purchase altogether,” he said. The group urges participants to “buy local and build community” when buying necessary items. Passionate groups can successfully target specific companies but often represent too small a fraction of consumers to significantly impact large businesses, Ernest noted. Conversely, large-scale general boycotts struggle to maintain focus and commitment. “If you’re boycotting all grocery stores and restaurants, the threat to the industries’ bottom line is less credible, as you’ll likely only spend slightly less, shifting many of your purchases to a non-boycott day,” Ernest said. Research from Northwestern University’s Institute for Policy Research echoes Ernest’s analysis, suggesting that many boycotts fail to achieve their stated goals, though they may generate media attention and raise awareness of issues. The blackout campaign has found support particularly within Black communities, with organizers emphasizing the economic power of Black consumers. They point to historical boycotts that achieved concrete results. The Montgomery Bus Boycott, which lasted from December 5, 1955, to December 20, 1956, successfully challenged racial segregation on Alabama’s public buses after Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a white passenger. The 381-day boycott proved highly effective—approximately 90% of Montgomery’s African American residents, who made up 75% of bus ridership, stayed off the buses, causing significant financial losses. The boycott ended when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that segregation on public buses was unconstitutional, and it helped launch Martin Luther King Jr. as a national civil rights leader. The Delano grape strike and boycott, which began in 1965, also demonstrated the power of sustained economic pressure. Filipino and Mexican American farm workers, organized by leaders including Cesar Chavez and Larry Itliong, struck California vineyards and launched a nationwide boycott of table grapes that lasted five years. In July 1970, major table grape growers signed contracts with the United Farm Workers that raised wages, improved working conditions, and established health benefits, affecting more than 10,000 farm workers. However, both successful boycotts shared characteristics that the current blackout campaign lacks: They were sustained over months or years rather than days, they targeted specific industries or companies, and they had clearly defined, achievable goals. The Montgomery boycott lasted more than a year, while the grape boycott continued for five years before achieving its objectives. The blackout movement’s organizers acknowledge they are attempting something different — a brief, broad demonstration of economic power rather than a sustained campaign against specific targets. Whether this approach can generate meaningful pressure on businesses or policymakers remains to be seen as the Thanksgiving shopping weekend approaches.