Copyright sandiegouniontribune

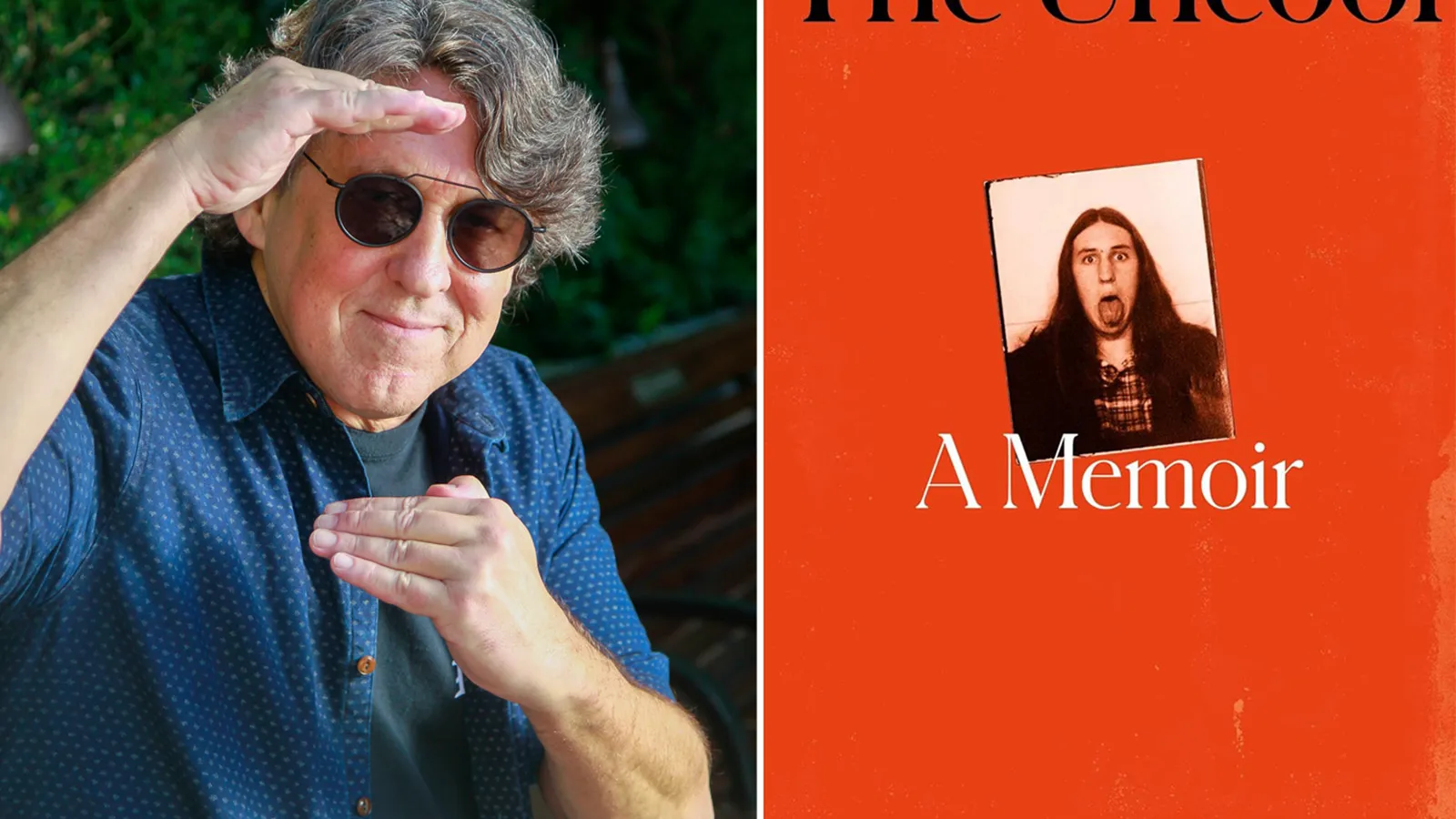

Cameron Crowe was understandably wide-eyed and elated in the 1970s as a San Diego teenager who traveled here, there and everywhere conducting in-depth interviews with The Allman Brothers Band, Led Zeppelin, Linda Ronstadt and other music luminaries for Rolling Stone magazine. He is no less so when recounting those experiences in his warmly engaging new memoir, “The Uncool.” Published Oct. 28 by Avid Reader Press, the book vividly chronicles Crowe’s experiences in an era when Rolling Stone was a must-read for many young people and an arbiter of nearly all things cool. It was also an era when some of the world’s most celebrated rock stars granted almost unlimited access to Crowe, the endlessly enthusiastic and completely guileless wiz-kid writer. Still a student at University High School in Linda Vista when his career as a music journalist ignited, he graduated three years early. “I looked younger than everybody. That would be my calling. My diploma came in the mail,” writes Crowe, whose book poignantly begins and ends in San Diego with his dying mother in the first chapter and his father in the last. Crowe’s fresh-faced passion and sincerity endeared him to even his most press-wary interview subjects. They welcomed the opportunity to open up to an interviewer whose questions were well-researched, who listened intently, wrote insightfully and whose only agenda was to let them speak freely to their fans. He had at least one other advantage: Crowe was an unabashed admirer of bands that most Rolling Stone writers viewed with disdain, including Yes, Deep Purple and the Eagles. He would go on to interview all three for the magazine. A drug-free teenager The fact that Crowe declined any and all offers of drugs from his interview subjects also endeared him to them, with one notable exception. A paranoid and glazy-eyed Gregg Allman was unnerved by Crowe’s abstention, including turning down a speedball (which mixed cocaine and heroin). So unnerved that — after pouring his heart out to the young writer — Allman demanded to see his ID card. That Crowe had yet to obtain his driver’s license incensed Allman, who accused the hapless 16-year-old of being an undercover police informant. Allman confiscated the tapes of Crowe’s in-depth interview with him and the band’s other members, and insisted he sign ownership over to Allman. Scared and under duress, Crowe reluctantly agreed. The tapes were returned, intact, a few days later. Crowe’s sensitively crafted article on the Allman Brothers earned him his first Rolling Stone cover story. What transpired also provided pivotal source material for Crowe’s Oscar-winning 2000 feature film, “Almost Famous,” which he wrote and directed. He also masterminded its rebirth as a musical in 2019, when it opened at San Diego’s The Old Globe before heading to Broadway. The longest chapter in “The Uncool” gives a blow-by-blow account of what transpired with the Allmans. As an epilogue to that sometimes-harrowing saga, the book later recounts the 2015 backstage meeting at the Del Mar Fairgrounds Grandstand Stage between Crowe and Allman. “Thank you for ‘Almost Famous,’” Crowe said. “You’re welcome,” replied Allman, who died in 2017. He was 69, just one year older than the still-youthful Crowe is now. Crowe’s teen exploits are the primary focus of “The Uncool,” which is also the title of his website. The name was inspired by former La Mesa rock critic Lester Bangs, who memorably cautioned Crowe about the status of music critics: “We’re from (expletive) San Diego. We’re uncool!” Crowe’s admiration for Bangs has never diminished, as he acknowledged in a 2023 Union-Tribune interview: “(Lester’s) writing presence could be powerfully sharp and almost scary-brilliant. He was reckless, and alive, and his banter had sound and fury in it. It read like music. And he was from San Diego!” Some of the most enjoyable parts of “The Uncool” are when Crowe provides fresh new facts and added context to events that inspired some of the most memorable scenes in “Almost Famous.” By disclosing previously unknown details, including the fact that he initially wrote the film as a starring vehicle for David Bowie, Crowe has produced a book that is part memoir, part novelization and all heart. San Diego valentine “The Uncool” also serves as a moving valentine to San Diego and Crowe’s family: his mother, Alice, a former San Diego City College professor and guidance counselor; his father, James; and Cameron’s two older sisters, Cathy and Cindy. Cathy suffered from mental illness and depression. Her suicide, at the age of 19, devastated her 10-year-old brother. He found solace in the records she had shared with him, including The Tremeloes’ “Silence Is Golden” and the Beach Boys’ “Don’t Worry Baby.” “Music was already more than music,” Cameron writes. “It was a door that opened for three minutes. Sometimes way longer. In the forbidden world (of music) there was no judgment. Only your own thoughts and secret desires … Sometimes I would listen to one song twenty or thirty times in a row. There had to be other people like me. I just hadn’t met them yet.” Cameron’s mother was his biggest champion. She was also his most trusted editor, sounding board and moral and aesthetic compass. Her aphorisms — including “Doubt is the devil” and “Only paranoids survive!” — account for more than a dozen of the chapter titles in her son’s 333-page memoir. Or, as Cameron put it in a 2011 San Diego Union-Tribune interview: “My mom is a real hero to me … (She) never gives up in making sure something she’s involved in is as great as it can be. She’s a person who’s always happy when something is serving humanity.” It was Alice who took 7-year-old Cameron to his first concert, a 1964 performance in a college gym, by Bob Dylan. While he was still too young to appreciate Dylan’s generation-defining impact, Cameron immediately grasped the significance of the moment. “The chilly gymnasium had become a gathering of a tribe,” he writes. “It was that rare feeling that we were all exactly where we belonged.” When the concert was over, Alice asked Cameron and his then-12-year-old sister, Cindy, how they liked it. Both responded effusively. Alice, Cameron writes, was quick to retort: “Well, someday the Republicans are going to ruin all of this, for everybody.” In addition to her liberal bent, Alice instilled in Cameron the importance of making every word he wrote, and every scene he directed, ring with truth and honesty. Despite her strong aversion to rock, Alice gamely accompanied her son to two San Diego concerts in 1970. The first was by a kitsch-fueled Elvis Presley (“in a glittering white jumpsuit … striking karate poses”). The second, just one week later, was by the galvanizing, Eric Clapton-led band Derek & The Dominos. (“I can still feel that night,” Cameron writes, “the private thrill of a committed audience, linking up with a committed performer …”). Capturing and conveying those private and public thrills would soon become the raison d’etre for Cameron as a young writer exploring the magic behind the music and the artists who made it. The uniquely personal and broadly universal ways a song can speak to — and for — its listeners enchanted the teenaged Cameron. It still does now, as “The Uncool” constantly attests. Eager to be as prolific as possible, Cameron also wrote for Creem magazine, the Los Angeles Times, Playboy, and other outlets. But his reputation was built as the youngest writer ever published in Rolling Stone (and, soon, one of its star contributors) — starting when he was 14 and interviewed Kris Kristofferson backstage at the San Diego Civic Theatre and in the lobby of the Mission Valley El Torito restaurant. His tenure at Rolling Stone laid the foundation for a career that has seen him pen three acclaimed books and write and direct such hit films as “Jerry McGuire” and “Say Anything.” He fared less well with “We Bought A Zoo,” which was set (but not filmed) in Jamul. Crowe’s current film project is a biopic on Joni Mitchell. He befriended her during a 1979 interview that was his final cover story for Rolling Stone. Mitchell had long held the publication in extremely low regard after being misogynistically slighted in one of its 1971 issues. Crowe acknowledges in “The Uncool” that he broke a major journalistic taboo by allowing the iconic singer-songwriter to read his cover story about her before turning it into Rolling Stone. By way of thanks, she gifted him with one of her paintings and signed it: “Thanks for the cooperation, Joni Mitchell.” Reflecting now on the painting she dedicated to him, Crowe writes: “I knew instantly I could never put it where a fellow journalist might see it.” By way of justification, he adds: “What might have been considered criminal to some journalists was a key to her comfort.” The comfort level musicians felt with Crowe is perhaps best demonstrated by his accepting an invitation to live with Eagles co-founders Glenn Frey and Don Henley while they were writing songs for their band’s next album. Frey and Henley had become pals with the young scribe when he interviewed them backstage at the San Diego Sports Arena in 1972. Frey went on to give Crowe advice on how to attract women and how to reject their rejection. A woman might leave you, or vice versa, but a powerful song will endure. ‘The Chipmunk Song’ A Palm Springs native, Crowe spent his childhood there and in Indio. He was 13 when his family moved to San Diego, where his world opened up dramatically. His love of music was already deeply rooted, as his mother recalled in a 2011 Union-Tribune interview.. “Cameron always loved music, since he was two weeks old, and I played him ‘The Chipmunk Song’,” she said. “He wouldn’t sleep unless I played him music.” Cameron does not mention “The Chipmunk Song” in his book. But he stresses how much his mother was opposed to rock and pop music, going so far as to write a letter to CBS executives complaining about a televised performance by — of all people! — Simon & Garfunkel. His mother and father, a former U.S. Army officer, wanted Cameron to become a lawyer. He had other plans, fueled equally by his love of writing and music. Cameron was inspired by Dick Cavett’s TV interview show and by the razor-sharp writings of rock critic Bangs, who would soon become his mentor and confidante. Cameron was 14 when he began writing for The Door, a San Diego underground newspaper. His first two interviews for The Door were with, respectively, United Farmworkers co-founder Cesar Chavez and comedian and Civil Rights activist Dick Gregory. “I was almost 15,” Cameron writes, “and had just taken a step into the world I wanted to live in.” During a subsequent single evening in 1972, he interviewed the bands Black Sabbath, Yes and Wild Turkey backstage at the San Diego Sports Arena. His life would never be the same again, even if doing big interviews in Los Angeles required him to travel there and back by bus. Cameron didn’t have a high school girlfriend or go to prom. But he was on a first-name basis with rock stars his classmates could only dream of meeting, let alone going on the road with those stars and sharing their innermost thoughts. His star-making tenure at Rolling Stone in the 1970s ended before that decade did, as punk-rock’s rise made Cameron’s specialization in classic-rock less desirable for the magazine. “I’m 21. I’m washed up.” he tells his parents. Happily, the decline of his music interview assignments prompted his shift to authoring his first book, “Fast Times at Ridgemont High,” which he researched here by covertly enrolling at Clairemont High School. Cameron subsequently wrote the screenplay for the movie version of “Fast Times,” which in turn led to his new career as an Oscar-winning filmmaker. The fact that he write so little about this part of his life suggests a second, cinematic-focused memoir may be in the works. “The Uncool” provides a welcome, in-depth look at Cameron’s formative years. Recalling a stay with his mother in San Miguel Allende when he was 7 and briefly attended a Catholic school there, he writes: “Though I would never have known it at the time, Jesus looks like Eddie Vedder, complete with a bleeding heart.” The book also has some curious omissions, at least for those San Diegans who have long embraced Cameron as a hometown-boy-made-very-good. While he references his time as a student at University High School, Cameron does not note that the first album review he wrote — of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Cosmo’s Factory” — was for the same school’s newspaper when he was 13. He also doesn’t mention co-founding the school’s underground newspaper, Common Sense, or his one-day tenure as a salesman at the Swap-A-Tape store adjacent to the San Diego Sports Arena. Later in “The Uncool,” the only mention of his “then-girlfriend” Nancy Wilson of the band Heart gives no indication they later married and had two children together before divorcing. Cameron wrote the extremely well-crafted liner notes for radio station KGB’s “Homegrown” albums in 1973 and 1974, but not a word about them appears in his book. Nor is there any reference to him also writing liner notes for a number of major albums, including “Frampton Comes Alive” by Peter Frampton, who had a cameo as a roadie in the “Almost Famous” film. The absence of both a table of contents and glossary may be a deliberate move by Cameron to encourage readers to take a deep dive into his memoir, much as they might when listening to a classic album in its entirety. Deliberate or not, “The Uncool” is a dive well worth taking. “The Uncool” by Cameron Crowe (Avid Reader Press, 2024; 333 pages) An intimate conversation with author and filmmaker Cameron Crowe: “The Uncool” Book Tour, with special guest Kate Hudson When: 7 p.m. Thursday, Nov. 13 Where: The Magnolia, 210 East Main Street, El Cajon Tickets: $66.50-$208.25 Online: livenation.com