Copyright The New Yorker

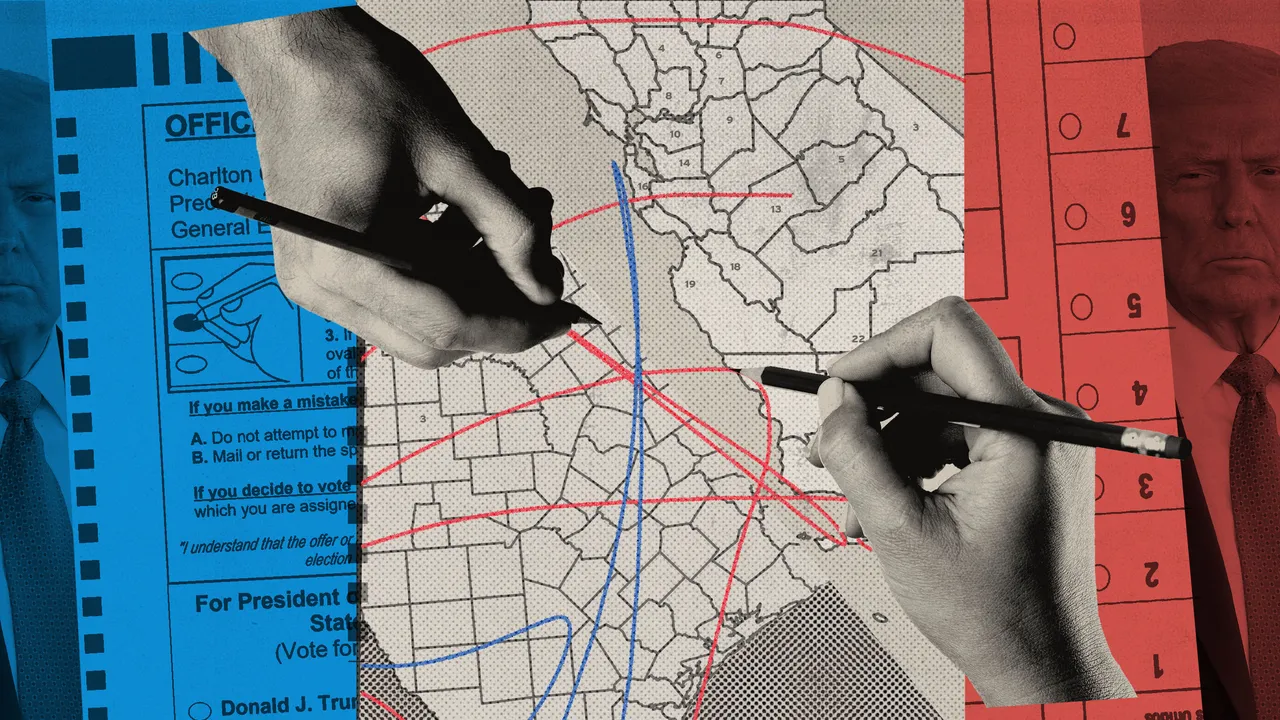

In July, as Republicans in Texas were pushing, at President Donald Trump’s behest, to change the state’s maps to net themselves as many as five more U.S. House seats in next year’s midterms, Gavin Newsom, the Democratic governor of California, warned that his state might feel compelled to respond in kind. “This is not a bluff,” he said. In fact, it was—or, at least, it had been at first. A month before Newsom’s pronouncement, as Politico has since reported, a senior House Democrat asked Paul Mitchell, the top redistricting consultant in California, whether a tit-for-tat would be feasible. Mitchell was skeptical, not least because the state had transferred responsibility for its congressional maps to an independent commission that was popular with voters. Nonetheless, Mitchell was dispatched to tour Texas media and “blabber about how easy it’s going to be for California to redraw our districts,” he told me. “We were trying to bluff the state that thinks they invented bluffing.” Over time, things got more serious. Texas rammed through its maps, even as Democrats in the state legislature absconded in an attention-grabbing, yet ultimately unsuccessful, attempt to deny quorum. Meanwhile, in California, Mitchell dug into the data and discovered not only that it would be possible to retaliate by drawing five friendlier districts for Democrats but that voters just might approve of the plan. And so Newsom and his allies teed up a ballot measure—known as Proposition 50, or the Election Rigging Response Act—that would ask Californians to sanction a temporary revision of the state’s congressional lines, with the proviso that the independent commission would kick back in after 2030. Opponents of the proposition got a boost when the former governor Arnold Schwarzenegger—the godfather, to mix movie metaphors, of the independent commission—warned that “two bad behaviors don’t make a right behavior.” But the “No” campaign ended up outgunned. Good-government groups that typically oppose partisan redistricting stayed on the sideline; former President Barack Obama got off of it to support Prop 50, despite his own past advocacy for nonpartisan mapmaking. On Tuesday, the polls closed, and the measure’s victory was called almost immediately. “We stood firm in response to Donald Trump’s recklessness,” Newsom said. “After poking the bear, this bear roared.” As Texas and California made their moves, the redistricting war spread across the nation. Initially, it looked as though Republicans, who currently enjoy a razor-thin 219–213 majority in the House—not counting an Arizona Democrat who has yet to be seated, after winning a special election in September—would have more opportunities to create favorable seats. Democrats, in the states they control, appeared hamstrung by a combination of institutional constraints, a lack of political will to circumvent them, and maps that were already disproportionately blue, making it hard to squeeze out further advantage. Last week, for instance, the leader of the Maryland Senate rejected a push to redraw the state’s sole Republican seat, citing both legal difficulties and philosophical opposition. (This week, Maryland’s governor, Wes Moore, pressed ahead, but it’s not yet clear how he’ll overcome the Senate-shaped obstacle.) Republicans, meanwhile, voted to nix the seats of two Democratic congressmen—one in North Carolina, and one in Missouri. But the Missouri seat may yet survive, at least into 2026, if opponents succeed in forcing a referendum on the new map. And a maneuver to remove a Democratic seat in Kansas has stalled, at least for now, as have similar pushes in Nebraska and New Hampshire, despite sharp pressure from Trump. The pressure has perhaps been most obvious in Indiana, where Vice-President J. D. Vance has twice dropped by to cajole state Republicans into carving out a likely extra seat or two. The campaign made some headway: one reluctant state lawmaker flipped from “hard no” to “hell yes,” citing (and you really couldn’t make this up) an epiphany during treatment at Indiana Spine Hospital; last week, the state’s governor, Mike Braun, called a special session to move the ball forward. But it’s still far from clear whether he has the votes. What is clear is that both parties are eying more targets: recently, Democrats in Virginia, who already controlled the state legislature and ran the table in off-year elections this week, unexpectedly commenced a plan to net up to three U.S. House seats next year, though the process is complex and the timing tight; Florida Republicans could flip even more, though that, too, is shrouded in uncertainty. Despite Trump’s efforts, it’s hard to say what impact the redistricting war will have on the balance of seats in the midterms, which, as of this week, are less than a year away. It’s even hard to say whether redistricting will wind up being the most egregious element of Trump’s wider efforts to keep the House under his control. David Daley, the author of “Antidemocratic: Inside the Far Right’s 50-Year Plot to Control American Elections” and “Ratf**ked: Why Your Vote Doesn’t Count,” told me that politicians have been trying to draw maps to their own advantage “for as long as we’ve had politicians.” The practice certainly predates the Massachusetts governor Elbridge Gerry, who, in 1812, signed off on a salamander-shaped district and wrote himself into history as the origin of the term “gerrymander.” Many parties—Democrats, Republicans, Democratic Republicans—have done it since, but what Daley calls “the modern era of redistricting” began in 2010, when Republicans gained control of key state legislatures and, armed with newly sophisticated software and voter data, began to exercise a more enduring “power to select winners and losers.” The timing was crucial: the 2010 G.O.P. wave coincided with the decennial census, which furnishes updated population data that sets in motion the drawing of new district lines. Trump has smashed precedent by triggering a mid-decade redistricting war that is divorced from the census. Sort of, anyway—this kind of partisan, mid-decade redistricting happened all the time in the late nineteenth century. (Ohio, for instance, redrew its congressional lines seven times in fifteen years.) The practice declined after that, but this had more to do with specific patterns of partisan control and polarization than an outbreak of good conscience, and in 2003 Texas (where else?) brought it back when state Republicans, then at a disadvantage in terms of congressional representation, forced a gerrymander through the state legislature. The new maps had “a revolutionary effect,” Lawrence Wright wrote in this magazine, in 2017. By then, Texas had twenty-five Republicans and eleven Democrats in its U.S. House delegation, “a far more conservative profile than the political demography of the state.” The skew in Texas mirrored national trends: in the wake of Republicans’ 2010 gains, Democrats could conceivably have won the national popular vote by five percentage points or more and not won a majority of House seats. But that advantage eroded, such that, by last year, “the party that won the most votes for the House was quite likely to win the most seats,” as Nate Cohn, the data maven at the Times, recently explained to my colleague Isaac Chotiner. There are a variety of reasons for this reversal. Several states created California-style independent processes that took map-drawing out of politicians’ hands, and some state courts overturned partisan maps. In others, Democrats aggressively countered Republican gerrymanders with their own. Changing voting patterns also played a role, as did (at least at the margins) what political scientists call “dummymandering,” a term—named for the Massachusetts governor Elbridge Dummy (just kidding)—that describes when gerrymanderers inadvertently spread their party’s votes too thin, or fail to correctly predict voter behavior. Especially since Trump first won, in 2016, “our politics have been very volatile,” Michael Li, an attorney focussed on redistricting and voting rights at the Brennan Center, told me. When politicians gerrymander, “you’re placing a big bet that you know what the politics of the future look like, and if you’re wrong, it can really backfire.” By way of example, Li pointed me, again, to Texas, where state legislative maps drawn to maximize G.O.P. gains after 2010 proved less advantageous by 2018, when suburbs of Dallas, for instance, swung to the left, and demographic shifts made heavily white districts more diverse. Last year, politics shifted again: Trump performed surprisingly well with Latino voters in Texas, according to exit polls, winning fifty-five per cent to Kamala Harris’s forty-four. Since then, his approval among Latinos nationally has receded, and, after Texas passed its new maps this year, some Democrats expressed optimism that Republicans in the state might prove to be dummies—that the projection of five new seats was based on a risky bet that Latino voters would stick with the Party at Trump-2024 levels. Mitchell, who drew California’s retaliatory maps, told me that his Texas counterparts may have made existing G.O.P. seats less safe. (Mitchell claims that his maps in California will offer Democrats pickup opportunities and shore up vulnerable incumbents.) According to the Texas Tribune, Republicans in Texas were reluctant to redraw the maps before Trump demanded that they do so. The independent data journalist G. Elliott Morris, however, told me that the Texas redistricting does not look like a dummymander, and other observers agree. (A lawsuit challenging the new maps alleges that they were drawn to distribute Latino voters who have lower rates of turnout in a manner that amounts to disenfranchisement.) Morris told me that, nationally, the worst-case net outcome of the current redistricting war for Democrats would lead to “potentially a pretty big drop” in representation. But predicting the precise number of seats they might lose is tricky, given that redistricting efforts remain in flux in several states—in addition to the purely partisan tit-for-tat, Utah and Ohio have been in the throes of mid-decade redistricting for mandated legal reasons—and, dummymanders or not, voter behavior can indeed buck expectations, especially in this era. (At least one Republican operative has expressed concern that moderate voters could punish the Party for initiating the mid-decade redistricting, which smacks of foul play.) Cohn told Chotiner that Democrats may have to win the over-all House vote by two or three points to gain the most seats in 2026—not a fair requirement, but hardly an insurmountable one given Trump’s unpopularity. If they fail, they won’t be able to blame redistricting alone. Well, they might be able to. Recently, the Supreme Court heard a case that could gut Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which currently prohibits racial discrimination in mapmaking and has been, as the law professor Atiba Ellis told NPR, “the most important check” on partisan gerrymanders in many G.O.P.-led states in the South. The weakening of Section 2 could swing as many as nineteen House seats in Republicans’ favor; even a lesser effect, per Cohn, would put Democrats severely on the back foot. Many observers expect the challenge to the V.R.A. to succeed. But it’s not clear whether the Justices will move in time for Republicans to reap the benefits next year. The Court normally issues decisions in June or July, and could explicitly state that its verdict doesn’t apply to the 2026 cycle. And even if it were to expedite the process and give G.O.P. mapmakers extra fodder, redistricting would not be the only dirty trick for Democrats to worry about next year. Trump, after all, seeks to tilt the playing field any way he can; just this week, he called the Proposition 50 vote in California a “GIANT SCAM” and warned darkly, if vaguely, that the process is “under very serious legal and criminal review.” Where does redistricting rank in light of all his other threats? Last year, I wrote about the term “election interference,” which was then being weaponized so liberally, not least by Trump and his allies, that it risked losing all meaning. I considered broad definitions of the term—under which partisan redistricting would very much fit—but Richard L. Hasen, an election-law expert at the University of California, Los Angeles, told me that he favored reserving “interference” for the most serious acts of subversion, such as manipulating ballots or changing results. We spoke again last week, and Hasen told me something similar: gerrymandering, he said, is “unsavory and it’s norm-breaking, but that’s not the same as saying that it’s illegal or interfering with an election” such that “the result no longer reflects the will of the people.” Recently, fears have begun to circulate that Trump could take more sinister steps to undermine the midterms, such as authorizing federal immigration raids around Election Day or dispatching the military to seize voting machines. Hasen told me that it’s too early to predict what will happen with certainty, but that he wouldn’t put any form of manipulation beyond Trump. Hasen’s biggest concern is troops being stationed in cities during voting—hardly unimaginable, in this climate. In this scary new world, partisan redistricting can look almost like politics as usual, even if Trump has pushed past the normal ways of doing it. But redistricting could help enable darker maneuvers; the Princeton professor Sam Wang has argued, for instance, that even if the two parties’ gains roughly cancel each other out, which he sees as likely, they will reduce the already low number of competitive districts, allowing Trump and his allies to concentrate, for instance, their preëlection ICE deployments and post-election lawsuits. And what is essentially cheating can only further erode Americans’ faith in the electoral system, especially when it is so overt. Texas Republicans may have cited (spurious) legal reasons for their redistricting push, but Trump, as he so often does, said the quiet part out loud when he claimed that he was “entitled” to more seats. Republicans around the country have since been similarly blunt. “They killed Charlie Kirk,” the Indiana senator Jim Banks said, in September. “The least that we can do is go through a legal process and redistrict Indiana into a nine-to-zero map.” Democrats have been blunt about their motives, too—though they can convincingly argue that, at least as far as this particular redistricting conflagration is concerned, they didn’t start the fire. And if tit-for-tat gerrymandering is going to happen, it might be some small comfort that it isn’t playing out in smoke-filled rooms, but in the light of day. Mitchell, the California mapmaker, maintained a very public profile during the Proposition 50 fight; one article, in Politico traced his journey from being a self-described “stoner” to, in Politico’s words, “the most powerful person in California politics.” (When I asked him about this, Mitchell, whose wife leads Planned Parenthood Affiliates in the state, responded that he is “the second most powerful person in California politics in my own household.”) He also insists that the maps California voters just approved don’t constitute a gerrymander at all, since the new lines don’t arbitrarily split communities. Not that he sounded entirely comfortable with being asked to magic up Democratic gains. “I am a progressive in my political leanings and in process,” he told me. “My greatest hope was that we would have stopped Texas from doing this to begin with. That was the entire plan.” ♦