Copyright newstatesman

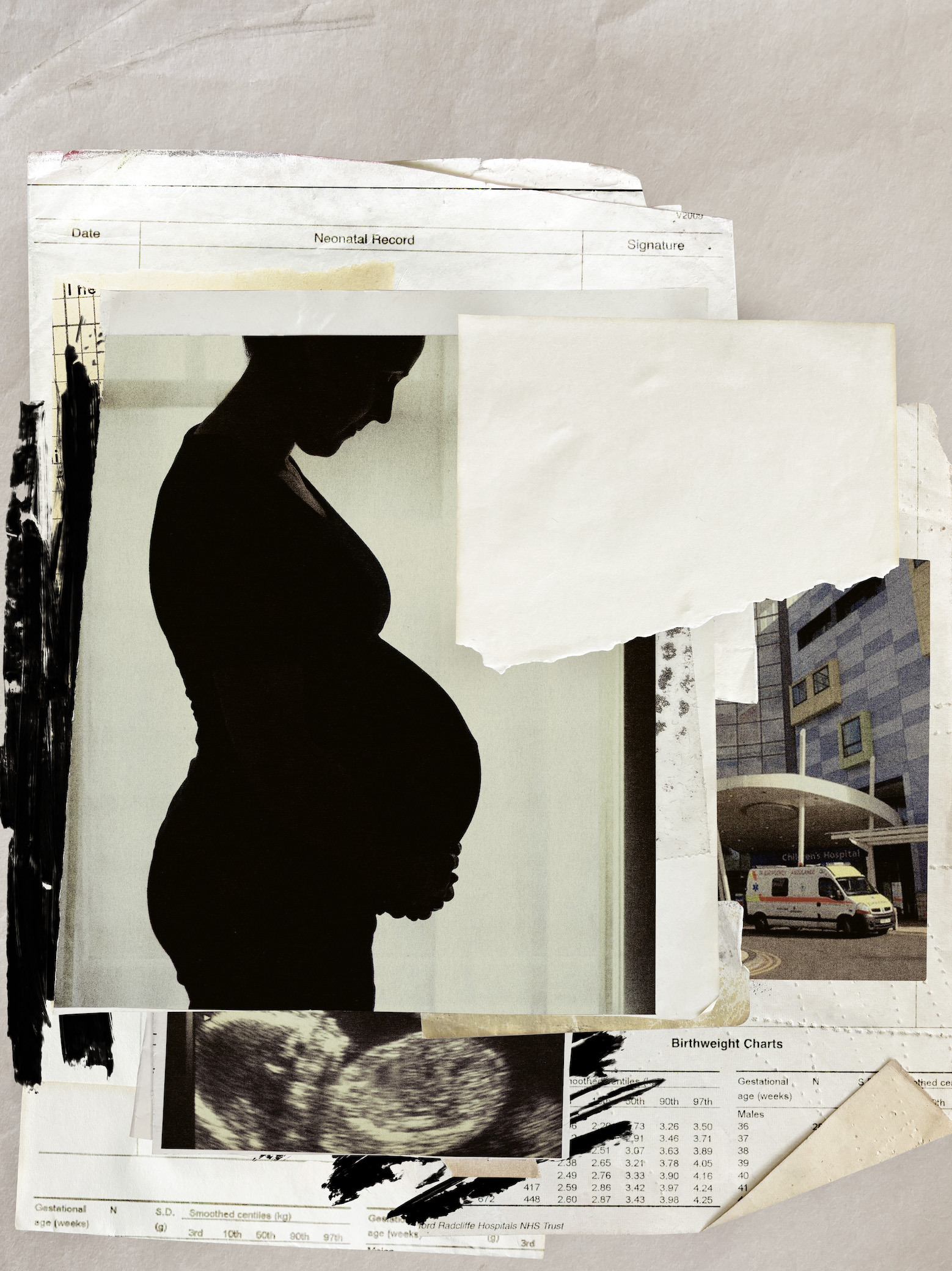

No matter how prepared or well-informed a woman feels, the months spent carrying a baby and the hours giving birth are among her most vulnerable. When she enters a hospital maternity ward, she places her life – and that of her baby – in the hands of medical staff. But in Britain today, that trust is being broken. According to the Care Quality Commission (CQC), nearly half of England’s maternity units require improvement or are rated inadequate. In the past decade, three major investigations have reported on maternity failings at individual hospital trusts. A fourth, reviewing the treatment of 2,425 families, is underway in Nottingham. A fifth, looking at Leeds, was confirmed in October. The failure is endemic and systemic – “a national scandal”, according to the Health Secretary, Wes Streeting. In June, Streeting announced a national maternity and neonatal investigation. Too many children have been dying, he said. In September, it was confirmed that 14 maternity trusts would be put “under the microscope” in a rapid review, as part of that investigation, led by the Labour peer Valerie Amos. Two trusts have since been removed from the list, but the inclusion of one, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (OUH), did not come as a surprise to the New Statesman. For four months, we – together with Channel 4 News – have been investigating maternity care at the trust, speaking with 24 women whose care spans from 2009 to this summer. We have heard harrowing accounts of stillbirths and neonatal deaths; met mothers whose children have been left with brain damage and who have themselves sustained lifelong injuries and mental trauma. All of this has been compounded by the institution’s defensiveness in the face of criticism, and its extraordinary reaction when those most affected have chosen to speak out. As we go to press, Amos and her team are in Oxford for a two-day visit as part of their work. But the details of our investigation go far beyond what the rapid review team can hope to uncover in 48 hours. Before publication we provided details of our findings to the Health Secretary, and we can reveal that he has since asked NHS England to examine specific allegations of failings outside the scope of Amos’s initial investigation. But this story is far broader than maternity-service failures. Streeting said the revelations were “scandalous” and pointed to a “moral failure” in the system overall. He continued: “I’m concerned about the extent to which we’ve got a… cultural problem across the NHS, where protecting the reputation of the NHS – and of trusts, sparing the blushes of executive leaders and clinicians – is prioritised over and above doing the right thing by patients.” That is a problem no inquiry, however big, can solve. “She was perfect, just dead.” Alice Topping is showing me photographs of her daughter, Smokey, who was stillborn at the John Radcliffe Hospital, one of the four main hospitals that form OUH, in September 2023. Two years later, Alice and her partner have been unable to move on. Instead, she says, they have spent that time investigating their child’s death. In 2023, the latest year for which data is available, OUH had the worst stillbirth rate in the UK. According to official perinatal mortality figures, OUH’s stillbirth rate has been graded red (at least 5 per cent higher than the average for comparable trusts) or amber (higher than the average rate but within 5 per cent) ever since these figures began to be analysed in 2017. Alice’s was a high-risk pregnancy. At 20 weeks, an ultrasound check called a uterine artery Doppler scan showed that blood wasn’t flowing between mother and baby as freely as it should. This, the leaflet she was given afterwards explained, meant there was a higher chance of the baby not growing as it should, or of Alice developing pre-eclampsia – a serious condition which, if left untreated, can harm both mother and baby. She wasn’t told that both conditions increased the risk of stillbirth. She was told she would receive “additional monitoring, scans and hospital or midwife appointments”. Complications arose late in Alice’s pregnancy. She developed gestational hypertension (high blood pressure) and possible pre-eclampsia, raising the risk of a stillbirth further. Like many expectant mothers, she hoped for a “natural” birth without an induction and wanted to give the pregnancy as much time as possible to proceed without medical intervention. She had no idea of the dangers she faced by waiting too long. At 38 weeks, the hospital agreed she could be induced when she reached nine days past her due date – a little over 41 weeks. Alice told us that she asked if the induction needed to be brought forward due to her hypertension and was told that it didn’t. Once again, no one explained to her that this could significantly increase the risk of her baby being stillborn. At the time, OUH’s policy was to induce women between 40 and 41 weeks, but as close to 41 as possible – even for those with risky uterine artery Doppler readings, or who had “well controlled” gestational hypertension. The New Statesman and Channel 4 News have spoken with four independent obstetricians about Alice’s care. They did not have access to her notes, but all said they would have induced a patient in similar circumstances by 39 weeks. In the final weeks of her pregnancy, Alice grew increasingly anxious as her bump measurement fell. She feared her baby had stopped growing, a sign that the placenta might be failing. She wanted a scan to check everything was safe. A midwife put in the request. It was declined, but Alice was not told about that decision. Waiting for an answer, she called the hospital 44 times in a single day, desperate to know what was going on and fearing for her baby’s life. A second request for a scan was also declined. “I just wish they’d brought my induction forward if they weren’t going to scan me,” Alice tells me. She now knows that the doctor who turned down the scan requests had in fact advised that the induction should be brought forward. But no one communicated this to Alice. Instead, she says she was told by a consultant obstetrician that “we don’t do scans from 40 weeks because we prioritise the 36-week scan”. Unbeknown to Alice, in 2016 OUH had introduced a new care pathway, which provided an additional scan for all expectant mothers at 36 weeks: the Oxford Growth Restriction Identification Programme, or OxGrip. Led by Professor Lawrence Impey, a consultant in obstetrics and foetal medicine, it aimed to reduce stillbirths by identifying those at risk, while “making best usage of resources, and restricting inequitable practice and unnecessary obstetric intervention”. As is standard practice, women are scanned at 12 and 20 weeks, but at OUH women also have a uterine artery Doppler at 20 weeks and the further scan at 36 weeks. High-risk women receive extra scans (as they would at other trusts). A universal 36-week scan is not recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice), “because current evidence does not show that routinely scanning all women with uncomplicated, singleton pregnancies conveys a benefit”. When the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) looked at the evidence again in 2024, examining later studies – including those discussing OxGrip – these “similarly demonstrated an unclear effect on perinatal mortality”. When the OxGrip research team published its first analysis of the pathway in 2023, it showed a reduction in perinatal deaths but one that was not “statistically significant”; it concluded the impact of the extra 36-week scan “on serious adverse outcomes remains unclear”. Alice believes that if she had been under the care of another hospital, Smokey would have survived. She fears the strain OxGrip puts on resources means scans outside the pathway are being denied – even in high-risk situations like hers. To make a scan for every OUH mother at 36 weeks feasible, there must be “strict policing of ultrasound requests”, an OUH consultant in obstetrics and foetal medicine, Christos Ioannou, noted in a 2018 presentation. “At least half of the requests are rejected.” More recently, in a presentation given at the International Congress of the Jordanian Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists in September 2022, his colleague Lawrence Impey explained the trust could “‘pay for’ extra scan [sic] by reducing others”. In national guidelines published by the RCOG, Nice and the NHS’s Saving Babies’ Lives initiative, the advice for high-risk pregnancies is that growth scans should continue at between two- and four-weekly intervals up until delivery. When Smokey died, Alice had gone more than five weeks without one. The independent obstetricians we spoke to said the request for a scan should have been accepted. While there is no legal requirement for NHS trusts to follow national guidelines, a consultant obstetrician, Ruth Mason, told the New Statesman and Channel 4 News that if a trust was operating outside of national guidance, they would “need to have evidence to show that what they’re doing is keeping their women safe”. King’s College Hospital, London, is one of a small number of maternity units other than Oxford that conducts a routine 36-week scan for pregnant women under its care. Panicos Shangaris, a consultant in obstetrics at King’s, told us this has benefits – such as reducing unexpected breech births – but that it’s expensive. King’s is only able to offer it, he said, because its equivalent of the OxGrip programme is funded by a charity, not the NHS. OUH has confirmed that it receives no extra funding to pay for its universal 36-week scan, but said it conducted these in addition to – not instead of – other clinically relevant scans. Alice’s trauma continued after the loss of Smokey. When OUH issued Smokey’s death certificate it incorrectly recorded that she had died before labour. Smokey’s funeral had to be delayed while a second certificate was issued. Then, when OUH investigated Smokey’s death, it found “no issues identified with the care provided” and concluded that nothing the hospital could have done would have made a difference to the outcome. To Alice, the initial report even seemed to suggest she was being blamed for her daughter’s death, in its claim that she “didn’t appear to be able to trust the clinical advice given to her”. The opposite was true, says Alice: she trusted them too much. When she read these words, she says, it felt like she had been “run over”. They had “left Smokey to suffocate to death inside me and then blamed me for her death”, she told me. An independent investigation by the Maternity and Newborn Safety Investigation (MNSI) programme – which investigates the deaths of mothers and babies and those left with brain injuries – drew very different conclusions. It made a series of recommendations based on factors it said had contributed to Smokey’s death, and noted that the trust’s “growth surveillance guidelines are not in line with national guidelines for ultrasound scans”. The MNSI investigation brought “some vindication”, Alice says, but she and her partner, Pedro, are still battling for Smokey’s death to be recorded as “avoidable” in official statistics. The local integrated care board, which oversees OUH’s budget, has noted there were issues with Alice and Smokey’s care that may have made a difference to the outcome, but so far the trust has not changed its records. Wes Streeting has now asked NHS England to investigate the “rationale” behind OxGrip “immediately”, including how it is monitored and evaluated, as well as its impact on resources. He told the New Statesman that deviation from national guidelines is only justified if it leads to “better outcomes and quality and safety”. He wants to know whether the extra 36-week scan is being deployed in “detriment to other services”. The scan protocol at Oxford University Hospitals trust is not the only area in which it has broken with national guidelines. Until 2021, the trust had an explicit policy of denying all maternal request Caesarean sections (MRCS) – a Caesarean where there isn’t a strict medical need – contrary to Nice guidelines published in 2011. In 2018, the charity Birthrights, which campaigns to protect the rights of women in pregnancy, found that 15 per cent of trusts had policies or processes that didn’t “explicitly” support these Caesareans; Oxford’s was singled out as being the harshest, and the group campaigned for it to be changed. The New Statesman has spoken to several women denied these elective Caesareans during this time. Some had to give birth in hospitals many miles away because OUH refused their Caesarean request. One was so traumatised by the experience that eight years on she still finds it difficult to celebrate her son’s birthday. She describes their bond as “weak”. While OUH’s policy on elective Caesareans was unusual in its rigidity, it was conducted against the backdrop of an NHS that was promoting “natural” – vaginal – births. Targets for reducing Caesareans and prioritising vaginal deliveries were introduced in 2012, recommended by RCOG, the National Childbirth Trust and the Royal College of Midwives. These targets were removed in 2022, but their legacy of harm to women and their babies persists. They have been cited as a contributory factor to poor care in the investigations into maternity services in Morecambe Bay, East Kent and Shrewsbury and Telford. A midwife who worked at OUH until 2023, Helen (not her real name), told me that even after the trust had changed its policy on MRCS in March 2021, a culture of promoting “natural” births remained. Medical notes, seen by the New Statesman, from later that year confirm that staff were required to “complete [a] promoting normal birth sheet” for all women – at both 16 and 36 weeks of pregnancy. Women would be shown all the benefits of a vaginal birth, Helen explained, but not the potential risks. C-sections and their potential benefits, meanwhile, were not proactively discussed as an alternative. “I’ve heard lots of women saying, ‘Oh, the obstetrician told me that my baby would have a better outcome if I had a vaginal birth,’ and so they felt that sense of guilt.” In a statement, OUH told us that it has consistently supported MRCS since the guidelines were updated in 2021. As a child in Sri Lanka, Gothami Hettiarachchi contracted rheumatic fever, which damaged the mitral valve in her heart. Doctors told her that, as a result, her heart wouldn’t be able to cope with a vaginal birth. When she became pregnant in 2017, therefore, she told midwives at the John Radcliffe that she needed a C-section. The hospital sent her for an echocardiogram to make sure, but concluded her heart issue was not causing issues with blood flow, and advised she did not need one. Gothami says hospital staff made multiple attempts to persuade her to opt for a natural birth instead. At every appointment, whenever a vaginal delivery was suggested, she broke down in tears. For years, she had lived with a fear of giving birth vaginally, having been told it would be dangerous for her. “It was engrained in my head,” she says. Still, she continued to engage with the hospital, unaware of its strict policy on MRCS. At 38 weeks, she and her husband, Peter, agreed to a final meeting before delivery. They were prepared to listen to the hospital explain the benefits of natural birth once more, but believed that Gothami would ultimately get the C-section she wanted, and had been told she needed. Instead, they were told: “Well, we won’t do it here.” Another hospital, more than an hour away, could have performed the MRCS had Gothami transferred there earlier, but now it was too late. At that point, Gothami says, she entered a “zombie state”. “I wanted to make a will,” she says. “I thought I’d die.” A letter from the consultant midwife who’d explained the OUH policy, confirms Gothami was “very distressed”. After four days in labour, Gothami had an emergency Caesarean after all. The stress of being told she’d have to have a vaginal birth against her will meant there was “no bonding at all” between her and her child. Again, the trauma continued long after the birth. When her catheter bag overflowed, the couple say they were told to change it themselves. At one point, Gothami believes she went for seven hours without medication, as did three other mothers in her room. They were told they had been missed because there had been a change in shift. OUH now says it recognises that some women had not been able to access MRCS in the past and apologised to those affected. It says it is committed to maternal choice. A recurring theme among many of the women I spoke to was what Laura Cook, a lawyer who has pursued medical negligence cases against OUH, describes as a “paternalistic” attitude. At Oxford, she says, care is “consultant driven, rather than patient led”. There is a sense that “they know best, or there’s no point explaining this to mothers because it will just worry her”. Doctors know best, and women’s choices are secondary. As a result, they are denied information they need to make informed decisions about their care. One devastating example is that of Emma Cox. In 2011 she was 17 and pregnant with twins, when an early scan revealed a rare complication. One of the twins, Hope, was bigger than the other, Lilly, who it was thought wouldn’t survive. Emma recalls being offered “repeated abortions” by her obstetrician, which she turned down. At 18 weeks her waters broke, and she spent much of her time from then in the John Radcliffe. At 24 weeks, she went into labour. After she had given birth, Emma says, she was told Lilly had died, and the baby was taken away. Hope, meanwhile, was resuscitated and taken to the neonatal unit. A short time later, Emma said, a midwife appeared with Lilly. “Unfortunately, she cannot be accepted into the mortuary,” the midwife said. Emma asked why. “Because she’s breathing,” came the answer. Lilly was wrapped in one of the hospital blankets, Emma recalls, and was full of colour. “She was pink, and she was moving her little hands and her little toes.” Emma and her family asked if Lilly could be moved to be with her sister in the neonatal unit. She says the hospital refused: Lilly had been without oxygen for too long and there was nothing that could be done. “I begged them, but they wouldn’t intervene.” Emma believes she wasn’t listened to because she was a young mother. The family placed Lilly – whose tiny body fitted into Emma’s hands – on a radiator to try to keep her warm. Later, Emma carried her tiny baby through the hospital to see her sister on the neonatal ward. There she was told that Hope was not going to make it. She died 12 hours after being born. Lilly, who received no medical intervention, survived for 24 hours. Fourteen years on, our conversation is the most Emma has ever spoken about the events of May 2011. She cannot bring herself to visit Hope and Lilly’s graves, nor to look at photographs of them. Everything relating to their short lives – blankets, prints of their hands and feet – is tucked away in a box in her parents’ garage. She has since had two more children, but remains terrified they will die: “I still wake up six times in the night to check that both of my children are breathing.” After making a complaint, Emma and her family attended a meeting at the hospital a few months after the twins had died. She asked directly whether, had Lilly been taken into the neonatal unit, she would have survived. “And they said: ‘There is the possibility that she could have survived.’” But because of the lack of oxygen, “she would have had profound learning difficulties or disabilities”. That was not the hospital’s choice to make, Emma insists. It was hers. At the time, Emma did not know she was part of a much bigger story. Then, in September 2025, she came across the “Families Failed by OUH Maternity Services” campaign on Facebook. The campaign had been started a year earlier by Rebecca Matthews, who had had a traumatic birth experience at the John Radcliffe in 2016. Emma says she was shocked to find so many others with stories like hers, and was struck by the similarities between the accounts: a lack of care and compassion, the denial of choice, and a dismissive attitude towards women. One member of the group, Eleanor Taylor-Verlaan, was 18 in 2017 when, 35 weeks pregnant, she called the John Radcliffe suffering severe abdominal pain, and reminding them that she had been classified as high-risk. She was told to take paracetamol and call back if the pain persisted. Later that night, in a terrible condition, she went to the hospital. The midwife attending to her was worried about the baby’s heartbeat but was, Eleanor recalls, “overruled by the doctors”. Her daughter, Alissa, was eventually delivered via emergency Caesarean, but died six weeks after birth. Eleanor had suffered a placental abruption, depriving her baby of oxygen and nutrients. An internal investigation rejected Eleanor’s view that Alissa could have been saved had staff acted sooner, but highlighted “suboptimal communication between healthcare professionals”. It said that, despite the midwife raising concerns numerous times, she “felt that the obstetric team dismissed her concerns”. Helen, the former OUH midwife, told me that midwives, particularly junior ones, were “not always clear how to escalate concerns”. Speaking up could be difficult because there was a “fear that you will be blamed”. When a birth hadn’t gone as well as it could have, she said, “rather than being helped and supported, you could be put down”. “We feel a lack of support from higher up, we feel alone.” Helen was keen to point out that this culture is not unique to OUH, but a wider problem within the NHS. Inevitably, it impacts mothers: “When as midwives we do not feel safe, women feel that too.” Part of Helen’s role was providing feedback to mothers after delivery and she regularly spoke with women who “didn’t feel that they had a voice” in the birth of their children. She was reluctant to criticise her former colleagues, who, she said, worked exceptionally hard. But she said “compassion fatigue” had crept in at Oxford. No one goes into the medical profession intending to harm patients, but staff can become numb to the suffering they see every day. “Families, women,” Helen said, “have been let down by the system.” And the impact of these failures can be mental, as well as physical. When I met Rachel and her husband, David (not their real names), at their home in Oxfordshire, their daughter Amelia was eight months old. She was the fifth baby Rachel had carried in two and a half years; her other four pregnancies ended in miscarriages. Amelia was desperately wanted. But the couple are unable to enjoy a normal family life. The mistakes and disjointed care that Rachel says she encountered have left her with such crippling anxiety that she is unable to leave the house with her daughter unaccompanied. “I’m so scared,” she tells me. “I haven’t slept more than three hours a night since she was born.” An alarm sounds at regular intervals, and Rachel lies there listening for signs of life. She cannot rid herself of the fear that her baby is going to die. In the day, their lives are accompanied by a constant clicking, like a metronome. The sound comes from a device Amelia wears at all times to monitor her breathing – not because she needs it, but because Rachel does. Just to know her daughter is alive. In response to two complaints, the trust has apologised for much of what Rachel went through: for a cervical scan referral that was lost and for the impact this may have had on her care. The trust also recognised that there were extended waiting times for perinatal mental health assessments across Oxfordshire, and said that work was underway to ensure that mothers were provided with consistent feeding advice. But to her, this means little. “People say to me, ‘But you and your daughter are both healthy.’ [But] if mental health was as visible as physical health damage, I would be completely covered in bruises and scars.” When the Families Failed campaign asked women for more details of their care, 229 responded. Nearly 45 per cent had given birth recently – from 2023 onwards. One in eight women had seen their babies die: 17 were stillborn, and 11 died shortly after birth. Fourteen babies were left with severe brain damage. Of 38 women who were denied an elective Caesarean by OUH, more than half went on to have an emergency C-section. A further quarter of those denied had deliveries that involved forceps or a ventouse, increasing the likelihood of a serious injury to the mother. To date, more than 660 women have contacted the campaign. To put that into context, when the ongoing investigation into Nottingham maternity services began in September 2022, around 400 families had come forward. But it is the “extremity of experiences” shared that surprise Matthews more than the numbers. “I don’t just mean poor care. It’s really severe: inhumane conditions, inadequate treatment, really harrowing experiences.” But, like the mothers whose post-natal care only served to exacerbate their trauma, the women who came together to campaign for justice following their experiences with OUH found their pain was only just beginning. On Thursday 21 November 2024, Naomi dropped off her eldest child at school, as she would on any other day. As she walked home, her phone rang. It was Thames Valley Police. “The police officer said, ‘Do you have any idea what this could be about?’” Naomi was mystified. A couple of weeks earlier, on 3 November, she had been at Thame Town Hall, in Oxfordshire, for the first face-to-face meeting of the Families Failed campaign. It had been advertised in a private Facebook group. Naomi was, the police officer said, now being invited to be interviewed under caution, in relation to comments she had made at the meeting. “Immediately I was crying down the phone to this man,” she says. “I was terrified I was going to be removed from my children.” At the town hall, Naomi had met nine others – women and their partners – who felt they had been harmed by OUH. One by one, the women told their birth stories. Naomi shared some details of the birth of her youngest child, sitting next to her in a wheelchair throughout. Her child had been left severely disabled after a difficult birth at the John Radcliffe in 2019. She spoke about the impact this had had on her family as well as her own PTSD diagnosis. The New Statesman has met five of the ten adult attendees at the meeting, all of whom corroborated Naomi’s account of the comments which later led to the police’s involvement. Everyone was in tears, they said, bar one: Joy Randolph. Unlike the others, she did not share a difficult birth story relating to Oxford but mentioned her history of birth complications elsewhere in the country. She has since told the New Statesman that she too had experienced poor care within the OUH trust – including being left without pain relief or food – after she had undergone a C-section at the John Radcliffe Hospital. At the time, some at the meeting wondered why she was there. Randolph stood out for another reason, too: she was insistent that the group should not pursue a formal inquiry into OUH maternity services, arguing such a campaign would scare women who were under the trust’s care. Naomi told me: “At some point in the meeting, I said this probably makes me a bad person, but sometimes I feel like locking the doors with everyone in it and burning the place down.” This was the comment reported to the police. It was not a genuine threat, says Naomi; they were the words of a traumatised mother expressing her despair. Someone else spoke up to say they sometimes felt that way too. “I wanted people to understand how strongly I feel about never wanting to go there again,” Naomi told me. “And yet my life means I have to go there – a lot. My youngest child is under the care of five consultants; four are based at the John Radcliffe.” A few days after the meeting, the group discovered Randolph had a number of links to OUH and to one of its senior obstetricians, Lawrence Impey. Impey had delivered her second baby by planned Caesarean section in his private medical practice in December 2021, and Randolph had spoken publicly and positively about this on a podcast, Birth Hour. Impey is also an unpaid medical adviser to Randolph’s commercial business, an app for mothers. In addition, Randolph is the public and patient involvement lead on the OxGrip research study, which is led by Impey. The New Statesman has also discovered that in June, Randolph was awarded a place on an innovation programme run by OUH, which grants NHS access to entrepreneurs hoping to introduce their technology across the health service. Noting Impey’s involvement, OUH has said such an arrangement “is commonplace” in all such projects, “where NHS clinical advice is a key factor”. A condition of participation is that OUH takes a small equity stake in each business. From public records filed by other companies also on the 2025 scheme, this is likely around 3 per cent. The trust has confirmed the association between Randolph and Impey was managed in full accordance with OUH’s conflict-of-interest policies. Around the same time, Randolph was appointed to the paid position of chair of the Oxfordshire Maternity and Neonatal Voices Partnership (OMNVP) – a group made up of parents, OUH staff and other regional health officials. Its job is to listen to mothers and contribute to the development of safe maternity services provided by OUH. When they learned of these connections, Families Failed removed Randolph from the group. It was then that Randolph reported Naomi’s comments to the police – eight days after they’d been made. At the police station, Naomi was shown a transcript. Randolph, it emerged, had recorded the meeting without the group’s consent. The officer in charge read out a statement Naomi had prepared and decided there was no need for a formal interview. There was no case to answer. (Both Impey and OUH say there was no prior knowledge that Randolph intended to attend the meeting or record what was said there; Randolph, for her part, was not necessarily doing anything illegal by recording the meeting, which she says was done for her personal reference only.) When we presented this episode to Wes Streeting, he said the act of recording the meeting without asking the participants first seemed a “sickening betrayal of trust”. “I have sat in those conversations with families, describing to me – a total stranger and a government minister – the most personal and distressing stories,” the Health Secretary told me. “The idea that I would record these stories, even for sort of an internal record, without asking permission, you just wouldn’t countenance it.” One year on, the incident has left Naomi feeling frightened, and her faith in humanity shaken. Matthews tells me she and others present feel like they were “infiltrated”. “It made us question who we could trust, who we could talk to. We were just trying to share our experiences in a safe space, to support each other because of what we’d been through as a result of the harm caused by OUH. And instead, that trauma was compounded by the actions following that event.” In a statement, Randolph said that she was “deeply sorry for the impact this has had on families” and acknowledged that their “privacy matters deeply”. She explained that she had gone to the meeting to meet other mothers and offer support, but felt “discomfort from the outset”. “That feeling of discomfort led me to hit record,” she said. Her motive, she said, “was self-protection in an environment that didn’t feel entirely safe”. She said she had been under no obligation to declare any interests, nor was she explicitly asked to. Randolph said she deleted personal or sensitive information from the recording, and that her record of what was said in the meeting had not been shared with anyone at OUH or within the NHS. The part shared with the police related to comments “about harm or intent to harm”, she said. Randolph said Naomi’s comment “did not feel like a throwaway or figurative remark.” She explained that her concern was heightened by the fact that another attendee seemed to express support for the comment, rather than making any attempt to de-escalate the situation. “Any allegations… that I made the report to ‘discredit’ or ‘derail the campaign’ are false,” she added. Randolph also says that as PPI lead on OxGrip, she had “never been paid by, employed by, or under contract with, nor volunteered my time for, OUH”. “Professor Impey asked to list me on the website in case he ever needed my guidance on patient and public involvement activities. To date, he has never asked for any support on OxGrip,” she said. For Rebecca Matthews, who began the Families Failed campaign, the controversy that followed the meeting was not an isolated incident. In the spring of 2021 – around the time OUH relaxed its policy on C-sections – she met with the trust to share what she had heard from more than 50 women who had previously been denied Caesareans under its care. Matthews was pregnant with her second child at the time and was concerned her campaigning would be used against her. She says the consultant and midwife present reassured her: “If anything, the care you receive will be better.” But when, in September 2025, Matthews received the notes relating to that pregnancy, she saw something extraordinary: a consultant from her first pregnancy had emailed the obstetrician she had met regarding MRCS, saying, “Now that you’ve met her, do you want her?! I don’t!!!!” “It was there in black and white that my patient advocacy work was being held against me,” Matthews told me. She has also learned from official documents that the backgrounds of members of the campaign have been discussed in hospital governance meetings. In a statement in response to our enquiries, the trust has offered its “sincere and unreserved apology to Rebecca Matthews for the inappropriate comment in her medical records”, calling it unprofessional and unacceptable. It says it had “thoroughly reviewed Rebecca Matthews’ clinical care and found no evidence that it was compromised in any way by her advocacy”. More shocking than the comments between OUH staff members, however, was the six-page letter Matthews received in August 2025, from the legal firm Carter-Ruck, on behalf of Lawrence Impey. The letter, seen by the New Statesman, demands Matthews “cease and desist” from her “campaign of publishing false and extremely damaging allegations concerning our client to third parties”. It accuses Matthews of spreading “grotesque falsehoods” and of behaviour constituting “harassment”. This, the letter argued, included: “repeatedly reporting our client to his employers, his colleagues and his peers, and the high volume of FoI [freedom of information] requests we understand that you are submitting… [about] OUH’s maternity services; our client, his work and his research”. It also says that the campaign’s work had led to “multiple parallel investigations” by regulatory bodies which were “generating a great deal of distress, uncertainty and additional work for staff, including our client, in an already under resourced sector”. Matthews denies the allegations made in the solicitors’ letter, and points out that at the time of the letter she had only made two FoI requests to OUH about its maternity services. She says that any complaints made to regulatory bodies, her MP or the Health Secretary were all made “in good faith and in the interest of public and patient safety”. In a statement to the New Statesman and Channel 4 News, Impey said that he was “sympathetic to the stated aims of the campaign”, and that it was “misleading and inaccurate” to characterise the legal letter as an attempt to “prevent fairly warranted criticism or concern”. He said the letter was sent after a “campaign of harassment and defamation”. Impey supplied us with examples of social media posts which named him, questioned his professionalism, and which he said were defamatory. These posts have now been removed. Matthews firmly rejects any suggestion of a sustained or defamatory campaign targeting Impey. In fact, she says, long before receiving Impey’s letter the campaign committee had already taken steps to remove members of the group for posting unacceptable content about OUH staff on social media. “The only thing I’ve done is raise awareness of women denied Caesareans,” she explained, referring to OUH’s previous policy. Laura Cook, a partner at CL Medilaw, has worked on medical negligence cases covering 25 years of births at the trust. She describes OUH as having a “very defensive attitude when things go wrong”, saying it will defend its reputation “to the hilt”. As an example, she recounts one case that reached its final settlement earlier this year. The details are harrowing. Mistakes at birth have left the child involved with severe brain damage – unable to walk, talk or feed themselves. In the days after the birth, the consultant responsible had sent a letter to the parents, “basically admitting that things had gone wrong”, Cook says. Yet, it took 12 years for the trust to formally acknowledge this fact and to agree compensation. A final settlement took a further three years. The scale of the reported harm at Oxford is extraordinary, but so too is its apparent lack of willingness to learn from mistakes, and the trust’s defensiveness in response to those who speak out. Exclusive figures obtained by the New Statesman from MNSI show that in the course of the 60 investigations it has completed into OUH care, the trust has been provided with the same safety recommendations year after year. In each of the four years from 2019-20 to 2022-23 inclusive, for example, it was advised to improve its monitoring of babies’ heart rates – after babies had died or been left severely injured under its care. A glance through the trust’s most recent board-meeting papers tells a similar story. Two years after Alice and Pedro’s daughter, Smokey, died, another child’s death was judged to have been potentially avoidable had it not been for the trust’s “unclear” policies “about offering a further scan for patients with new onset hypertension with additional risk factors”. The Families Failed campaign group wants to prevent others going through what its members have, Matthews explains. Yet “we are treated as though we are the people who deserve to be punished”, she says. In the course of this investigation, I heard the stories of many more women than I have space to tell here. Women who say they were left alone for hours, not knowing whether their babies were alive or dead. Who say they were, in these most vulnerable moments, denied the care they begged for. Who sustained injuries so severe that their marriages failed because they were unable to have sex. Who say they were left without pain relief or food, or lying in gowns and sheets soaked in their own blood. Who, like Gothami, recount being left with overflowing catheter bags. Who felt like “pieces of meat” or that they were treated “like animals”, or who were made to feel like they were an inconvenience. Who say they were told by medical staff that, despite it all, they were “lucky” to have been treated at the world-class Oxford University Hospitals trust. Oxford University Hospitals trust has not challenged any of the personal stories of care provided here. In a statement, its interim CEO, Simon Crowther, said: “We extend our heartfelt apologies to any family who have not received the standard of care they deserve and our condolences to those who tragically have experienced loss.” The trust welcomed the opportunity provided by the Amos rapid review to reflect and improve its care and said that it had – in recent years – strengthened maternity services by recruiting 54 additional midwives and improving clinical training. “However, we recognise that there is much more to do,” Crowther said, “and we remain resolute in our determination to go further.” The trust said it is keen to meet with the Families Failed campaign and work together to “build a service that is safe, compassionate, and responsive to the needs of all families”. Crowther thanked all those who had shared their experiences during our investigation for speaking up. “We apologise that the care you received was not of the high standard we strive to provide,” he added. The kinds of problems we have identified at OUH are not confined to the past – similar cases were taking place even as we were investigating this story. One woman, Joanna (not her real name), should still be pregnant today. From previous pregnancies, which had all been under the care of the John Radcliffe, she knew she had a weak cervix. During this pregnancy, also at the hospital, she twice mentioned her cervix issue to the midwives and asked is she needed to see an obstetrician. She was told she would be notified if it was thought necessary. On a Friday morning in August 2025, Joanna noticed some brown discharge and called NHS 111. She was just 20 weeks pregnant – four weeks before a premature baby is considered viable in the UK. The paramedics who attended took her to hospital. There, Joanna told us, she was seen by a doctor who said to her: “Joanna, you’re in labour. Your baby will be born. She will be born alive. But there’s nothing we can do.” The baby, Evelyn, survived just a few hours after being born. The birth was complicated, and afterwards Joanna was rushed to theatre and told she would die if her placenta was not removed. By the time she returned from surgery, Evelyn had died in her father’s arms. “Evelyn was placed in a little basket so I could hold her,” Joanna says. “I was left for hours in that room, and all I could hear were babies being born. And I was holding my baby, but she didn’t cry. They just left me. No one came in and said, ‘Are you OK? Do you need anything?’ No one came in.” When she was eventually seen by a doctor, she asked: “It was my cervix, wasn’t it?” Joanna says the doctor admitted: “We should have been keeping an eye on [it] sooner.” She had feared this would happen, and no one had listened. “There were loads of different things that could have been done to prevent my baby from being born prematurely, and none of it happened,” she says. “And no one’s been held accountable for it.” Despite Evelyn’s death being so recent, Joanna wants to speak publicly about it. “I will fight anybody for my daughter, because she should still be growing inside me now,” she told us. “We should still be buying baby things… Instead, our weekends involve going to the cemetery and giving her fresh flowers.” Like every grieving and traumatised woman I have spoken to during this investigation, Joanna wants change. These women do not seek revenge. They want an honest explanation for what went wrong during the births – and in some cases deaths – of their children. But most of all, they want to prevent any other family from going through what they have endured. [Further reading: The trauma ward]