Copyright The Boston Globe

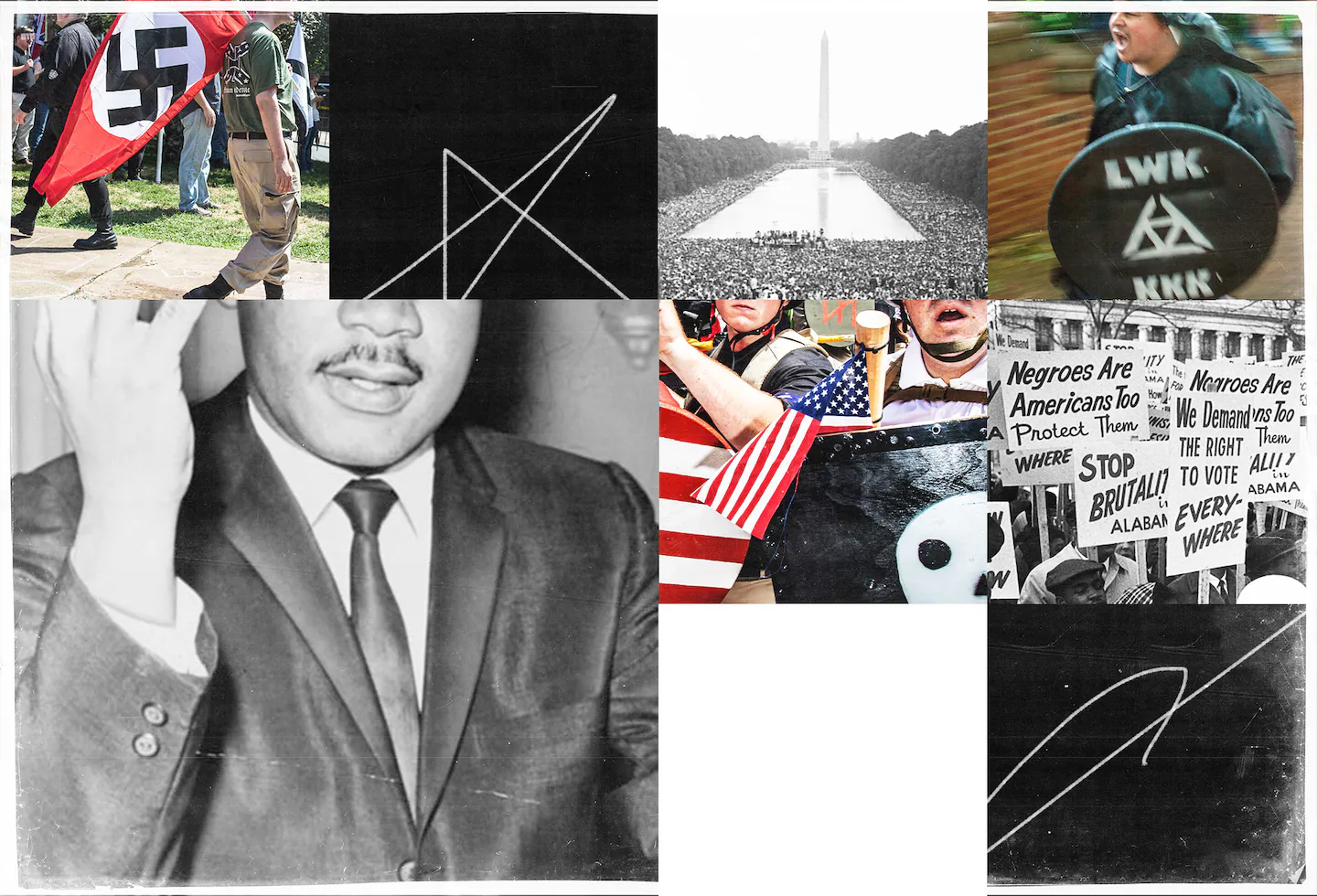

Terry’s book, which was released last week, helped me make sense of the moment in which we find ourselves now. His dismantling of some of the myths we tell ourselves about the civil rights era and its place in the story of America, for example, helps explain why we feel stuck in a period of regression — with a repressive, reactionary movement successfully propelling Donald Trump to the presidency not once but twice — and why liberals, including the Democratic establishment, seem especially unprepared, or even unfit, to lead us out of it. So what, exactly, is flawed about the way that we as a country remember the civil rights movement? One glaring problem is that we’ve essentially mythologized it and turned it into a classical, almost biblical, tale of good inevitably defeating evil. “Trying to tell a triumphalist story of good over evil, you lose a sense of why racial inequality is so intractable in the United States,” Terry said in an interview. “In fact, it can lead you to turn the story around and make the people left behind by the civil rights movement the villains in their own personal tragedy — that they were the ones that couldn’t bring themselves, through personal discipline or corrective behavior, to take advantage of the opportunities that people like Dr. King sacrificed so much for.” Indeed, since the landmark legislation of that era, including the Voting Rights Act, Civil Rights Act, and Fair Housing Act, came into effect, one recurring argument on the right has been that racial inequality in the United States is no longer primarily a result of systemic discrimination but of personal responsibility — that Black people themselves are to blame for the inequality they face. But that triumphalist “good vs. evil” story doesn’t just result in this kind of “pick yourself up by your bootstraps” mentality among conservatives; it also leads to a liberal movement that can’t adapt to a changing world. Take, for example, the way former President Barack Obama often spoke of the civil rights movement and its leaders. At the 2011 dedication ceremony for the Martin Luther King Jr. memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., Obama said that despite its flawed and sometimes dark moments, America’s story is still one “of optimism and achievement and constant striving that is unique upon this Earth.” And King, Obama argued, embodied that story. “As tough as times may be, I know we will overcome. I know there are better days ahead. I know this because of the man towering over us.” In telling King’s story this way, Obama implied that the success of the American civil rights movement was somehow inevitable. “One of the key problems is that I think there’s a fetish buried in the heart of romantic stories, which is that good is definitely going to triumph in the end,” Terry says. Obama’s speeches, Terry says, suggest that “we’re all in some kind of fundamental agreement about the things that matter and that our antagonisms aren’t as deep as they seem, reconciliation is in our grasp, [and that] good is going to win out in the long run.” “It’s obvious why those sentiments would be ones people want to be true or find seductive,” he continues. “But I don’t think they have warrant, and the world we’re living in now suggests exactly why: We do have deep disagreements — some about the fundamental questions of whether all men are created equal.” The way liberals remember the civil rights movement, in other words, tends to ignore the fact that those deep disagreements that defined that era — disagreements about what full and equal citizenship means — are still with us, even if we’ve come a long way since the days of Jim Crow. So when the Republican Party started to embrace white supremacist factions more openly under Trump, many liberals were taken by surprise, because they assumed that this kind of ideology had already been relegated to the ash heap of history. The way Obama tried to contain the more extreme and racist ideas on the right “was by depicting his opponents as always on the wrong side of history … and that’s seductive because it suggests that your opponents have already been defeated by a kind of underlying movement that you represent,” Terry says. “To me, it represents the desire to win at politics without engaging in politics, to have political victory without genuine conflict.” To see the civil rights movement’s success as something that was predestined — achievable because of a presumption that America is inherently good despite the country’s profoundly racist history — makes people all the more uncomfortable with conflict in the present day. Obama himself seems aware of how that viewpoint, which he promotes, can lead to passivity. “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice,” he said recently. “Except it doesn’t bend on its own — it bends because we pull it in the direction of justice.” The problem is that although Obama hints at the need to engage in uncomfortable conflict to achieve justice, his overall rhetoric during his political rise and his presidency shied away from genuine confrontation. That’s also true in the Democratic Party establishment more broadly, because there’s a sense that the George Wallaces of today are doomed to fail because good always defeats evil. “One of the ways you could see this is how liberalism is prone to describing its opponents in the most highly valent negative terms, with references from the past — the Ku Klux Klan, the Nazis, the fascists — while never seeming to countenance the kinds of political strategies and political responses that actually defeated those movements in the past,” Terry says. “If the monstrous has indeed been exhumed from the grave to stalk us once more,” Terry writes in his book, “why are the strategies that vanquished them in the past — state repression (e.g., President Dwight D. Eisenhower federalizing the National Guard to integrate Little Rock Central High School or the Federal Bureau of Investigation infiltrating the Ku Klux Klan), mass civil disobedience (e.g., the 1963 Children’s Crusade in Birmingham), and political violence (e.g., the organized self-defense used to protect Congress of Racial Equality and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee activists in Mississippi) — unthinkable in the discursive and institutional spaces of liberal political reason?” That’s why the old romantic tale of the civil rights movement can lead to political paralysis today. “In this way,” Terry writes, “romantic consciousness congeals into a structure that permits the abdication of political responsibility while narratively conjuring self-satisfaction and moral certitude, even in times of crises where the common sense that once made its worldview plausible erodes under our feet.” Instead, Terry argues that it’s better to think of the civil rights movement in tragic terms. He doesn’t mean tragic in the colloquial sense, as in something awful or inevitably doomed. He uses the term “tragedy” in the philosophical sense, as a way of understanding the human condition — one that is filled with constant conflict and defeats and yet is still infused with hope for a better world. This allows us to reckon more seriously with the defeats the movement faced. “Tragedy says, no, let’s not only look at the victory or try to turn everything into a victory. Let’s be honest: There are a lot of people who are on what [the philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich] Hegel called the slaughter-bench of history,” Terry says. “Their lives were destroyed by Jim Crow. They’re not redeemed by the doors that opened up for someone like me at Harvard.” That sense of tragic loss can improve our judgment of our present-day struggles, especially when we consider the parts of the civil rights agenda that never came to be and that should not be forgotten in the name of compromised victory — from fighting for economic justice to fiercely opposing US militarism. Viewing the civil rights movement as a tragedy doesn’t necessarily lead to hopelessness or an unwarranted satisfaction with the world as it is. It also rejects the pessimistic view espoused by some scholars that US society is so fundamentally racist that true equality and emancipation for Black Americans will always be out of reach — that even the civil rights movement essentially did little or nothing to tear down the deeply entrenched structure of subjugation. “The pessimist tells you that nothing is ever going to change; no matter what you do … it’s always going to be the same,” Terry says. “Ask yourself, what does that do to your judgment over time? It trains you to look at everything as always already foreclosed.” Instead, Terry’s interpretation of the civil rights movement inspires what he calls a tragic hope — the idea that because we have agency, we should still fight for progress even if victory is not guaranteed within our lifetime or ever. It’s an empowering view that underscores the political responsibility we all have to act, to do something, because the future is not yet written. After all, we ultimately do not know if we as a society are doomed to fail or destined to succeed. But resorting to cynicism or a tolerance for the status quo will only lead to passivity and inaction — something that not only denies the possibility of a better world but potentially contributes to making matters worse. “Tragedy makes no commensurate promise or guarantee of what will follow from our acts or in what manner, but this unpredictability lays bare our tremendous responsibilities to the past and the future for passing on what we want to survive and disavowing what we do not,” Terry writes. “Most challenging of all, tragic hope takes seriously the possibility that we are not, yet, in the worst of all worlds, and it is part of our responsibility to prevent further catastrophe from coming into being.”