Copyright business-review

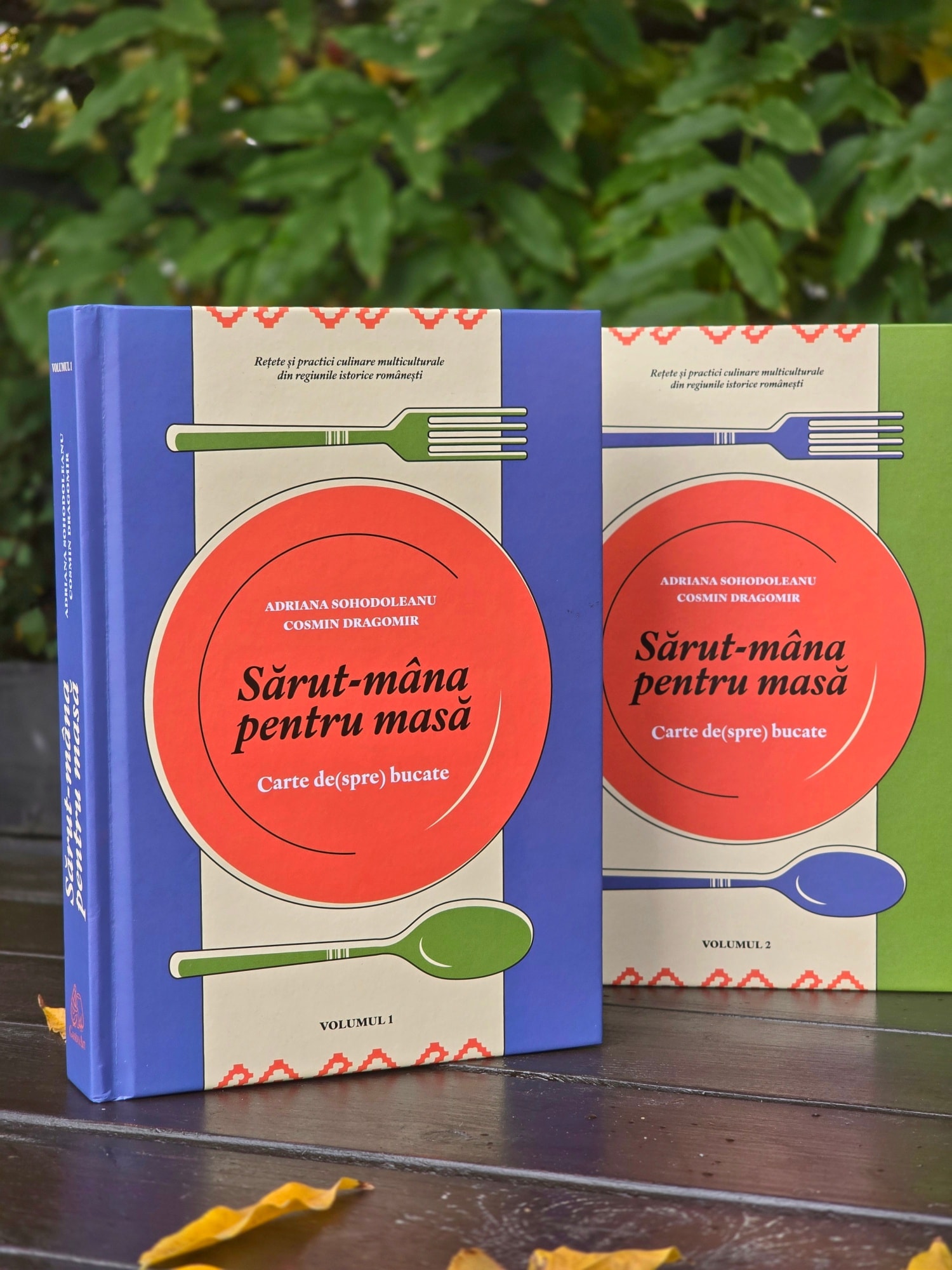

In a country where recipes were long whispered, not written, and where the gesture of sărut-mâna pentru masă (in English: thank you for the meal) once carried both gratitude and affection, Adriana Sohodoleanu and Cosmin Dragomir bring back a vanishing world: one plate, one story, one forgotten word at a time. Their monumental project, Sărut-mâna pentru masă, is not just another cookbook, but a cultural atlas that translates Romania’s culinary identity for today’s readers. Combining academic rigor with narrative warmth, the duo turns food anthropology into a living, breathing language, one that reconnects generations, preserves regional voices, and proves that Romania’s most authentic stories are still being told at the table. For Business Review, anthropologist and food researcher Adriana Sohodoleanu, co-author of Sărut-mâna pentru masă, talks about how Romania’s culinary heritage is more than recipes, it’s a living archive of beliefs, rituals, and community ties. How did the idea of Sărut-mâna pentru masă emerge? It all started in Maramureș, the northern region that still keeps so much of its traditional lifestyle. I was visiting and, like I always do everywhere I go, I wanted to buy a local cookbook. There was none to find, and it dawned on me that actually, with the exception of maybe Transylvania only, personally I have never seen a Bucovina-, Muntenia-, Oltenia-, or Moldova-focused cookbook. Even more important, I missed and regretted the absence of printed material that shows all ethnicities living traditionally alongside Romanians. I wanted to chart as much as possible everything they are bringing to the table, because multiculturality weaves a rich tapestry. So I called Cosmin and asked him if he’d be interested in joining me in writing such cookbooks. The rest is history, as they say. In Romanian, “sărut-mâna pentru masă” is both gratitude and affection. What does that phrase mean to you today, after this long research journey? Sadly, the expression is rather lost now; there are so few instances when we hear it, and this goes along well with the disappearance of the old world. Our book is about gratitude and affection, and a weapon against oblivion. I particularly liked to fill in the expression when I was a child – sărut-mâna pentru masă, că a fost bucătăreasa grasă și frumoasă (in English: My compliments for the meal, clearly made by a cook both beautiful and chubby) – it expresses a way of seeing food as essential, checking all boxes: beauty and health (in a world deprived of basic sustenance, fat meant well-fed, a condition for survival). You’ve described this project as much more than a cookbook, almost an anthropological fresco. In what ways does it challenge the typical format of a recipe collection? I like to refer to it as an almanac, because the variety and structure of the information and its display/formatting are an homage to the Almanah literar-gastronomic, published in the 1980s. I wanted to show the richness and diversity of functions, dimensions, and symbolism food holds in the traditional lifestyle, and that meant documenting it in its various expressions – religious (pagan & Christian) beliefs and rituals, festive & rites of passage (weddings, baptism, burial), communal (clacă as a way of getting things done with the help of the community, be it harvesting or building a house), medicinal, magic, or sheer creativity to feed a crowd. So it is the amount and diversity of such data that mirror the recipes on each community’s table and make our book more about food than cooking alone. How did you approach the fieldwork process? What did a day of culinary research look like – between archives, kitchens, and local storytellers? I started the desk research in winter 2023 and acted like the proverbial ant, just reversing seasons – gathering provisions to make summer easier in terms of traveling for the field work. The nice surprise was the tons of papers and even books written by Romanian researchers working for institutes and museums, publishing amazing research which often remained known and appreciated only in academia. This is when we jointly decided the world did not need more people interviewing villagers, but a more commercial approach, one that popularizes the existing info in a more digestible way. So we planned our field work as the cherry on top, for local flavor and personal immersion. The many months we spent like this were very antagonistic – from the hundreds of pages to be read to the bounty our informants bestowed upon us, both as information and dishes to be gorged upon. Romania’s culinary identity often lives through oral transmission, recipes passed down from mothers, grandmothers, or neighbors. What was it like to document these living memories before they vanish? It is a special moment when someone opens up and shares childhood memories – what makes it special is the age and beliefs of the informant. Young people today (over)share private info lightly, maybe overestimating a bit their value, but older generations are more private, often because they do not see value in what they have experienced. Also, we are lucky to still have people who can share things they’ve done, lived, or witnessed firsthand. In a decade or so, this will no longer be possible, so acknowledging this places a weight, pressure, and responsibility. Since we decided to limit our field work, I am extremely grateful for the existence of the brand newADELIS, a culinary recipes atlas, a project coordinated by the Romanian Academy all over the country – there are over 2,000 recipes, so our heritage is safe. Your book brings together Banat, Bucovina, Crișana, Dobrogea, Maramureș, Moldova, Oltenia, Muntenia, Transylvania, and even Moldova beyond the Prut. How do these regions coexist gastronomically? What unites them and what divides them? That is a very tough question – food intake patterns are shaped by geography, agro-pastoral and religious calendars, not to mention occupation, colonization, but also community values and confessional structure. I reserve the privilege of offering my two cents sometime in the future, when I will have had the chance to analyze the data we collected so far. You and Cosmin Dragomir insisted on including all voices, majorities and minorities alike. How does Romania’s ethnic diversity reflect in its culinary landscape? I have been adamant in including all minorities, to give their cuisine and associated practices, beliefs, and traditions a voice. It is important to know we are in this together; we all put something on the table, and I mean that in a more generous way, not limited strictly to food. There are so many taste profiles and narratives in every region, and all make a deliciously diverse, multicultural Romania that needs to be appreciated – but that comes only with knowledge. This is what our book hopes to achieve. You mention a “culinary lexicon in danger of extinction.” Which words, techniques, or ingredients struck you most as being on the verge of disappearing? This idea of including words, sayings, etc. was inspired by my mother’s vocabulary, which never stops to amaze me – there are always new terms to learn and love, and maybe mourn – some were used to express ingredients, techniques, or objects of material culture that are no longer needed or not used as much. We have farfurii, not talere; we raise our cakes with sodium bicarbonate, not solocară, and bake them in a tray, not on a lespede in the oven, not on a șpor. How many of us know the difference between hapor and hărănaci (gullible vs. gourmand) or that marjo is the name of the meal offered the day after the wedding in Maramureș. The book seems to trace a living geography of Romania through food. What surprised you the most in terms of how geography, mountains, plains, rivers, shapes what and how people eat? I am happy to report that food is so close to one’s core that there is almost always a strong reaction to anything perceived as being different, straying from what they know. Nu se face așa! – This is not how it’s done. I learned a traditional recipe for snails with lovage and polenta in a Moldavian village, but 30 km away people swore nobody has ever eaten snails in Moldova. I am starting to love the relativism! If you had to describe Romania’s gastronomy to an expat discovering the country, how would you capture each region in one dish or metaphor? For instance, what dish tells the story of Transylvania? What flavor defines Oltenia? What ritual captures the spirit of Moldavia? Oltenia is burnt by the sun, so food is spicier, to keep cool body and temperament. Moldova is about love of God and food, so make sure you go there when there’s a hram (celebration of the church’s patron saint), and Transylvania could be represented by a smoked pork, sour cream, and tarragon soup. It is difficult, if not impossible, to reduce a region to a dish or even a meal – we tried to create a multicultural menu for each and failed because of the richness of options, which made selection painfully unrealistic. You’ve mentioned the concept of Via Gastronomica, a route connecting local inns and restaurants through authentic regional menus. How do you see this developing? Could Romania become a culinary destination in its own right? We knew before starting work on this project that Romania can easily be a gastro-touristic destination. The book gave us irrefutable proof to convince those willing to listen to reason, arguments. Unfortunately, I met people so disappointed about the wasted potential that they have closed their eyes, minds, and hearts, and getting to them will need so much more than a book. What do you hope readers, Romanians and foreigners alike, will take away from Sărut-mâna pentru masă? Is it a call to preserve, to cook, or perhaps to listen more closely? I would be happy they do any of them, better all – preserve, cook, listen. Just like the Almanah literar-gastronomic showed me that food is so much more than fuel, I would be so happy to reach even a small number of young people and convince them Romania is exotic and delicious when it comes to food. There is a lot to be proud of here. The books can also be a tool for restaurant owners, chefs, and cooks to differentiate their offer and build a menu that reflects the local, seasonal tradition. The book is available in Carturesti stores and online, in Romanian only. Photo credit: Ciprian Muntele