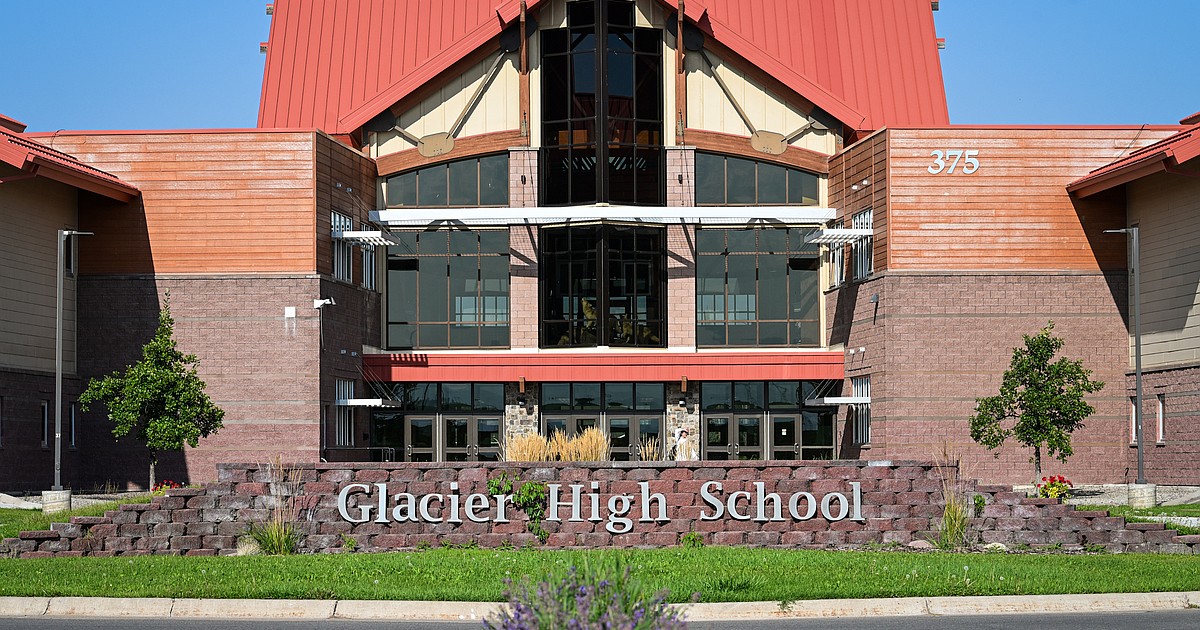

After 20 years, the bonds used to build Glacier High School and renovate Flathead High School are paid off.

Voters initially approved the $39.8 million bond issue for both undertakings in a Nov. 2, 2004, election. In the same election, voters approved a $10.9 million bond issue to renovate Kalispell Middle School.

In 2004, it was the largest school bond issue of the decade in Flathead County and overhauled the configuration of where students attended school throughout their K-12 education in Kalispell Public Schools.

With the $39.8 million high school bond issue off the tax rolls, about $15.4 million will be collected in local taxes as opposed to $18.1 million, according to Kalispell Public Schools Finance Director Chris Campbell.

Taxpayers also saw property tax relief after the school district refinanced the bonds for the high schools and middle school in 2019, which translated to approximately $1.3 million in savings.

PAYING OFF the bonds that built Kalispell’s second public high school, which opened in 2007, is a milestone to celebrate, former administrators said.

Darlene Schottle, who was the superintendent at the time, said it was a challenging community effort to get everyone on board with splitting into two high schools. Before Glacier was built, Flathead was the largest high school in the state. It was also steeped in tradition, according to Callie Langohr, a former Flathead principal who served as Glacier’s first principal.

“Anybody that had lived here a long time had gone to Flathead High School,” Langohr said. “The black and orange ran pretty deep in the community.”

Schottle said the process required a mindset change in how schools operated.

“It wasn’t just building a new high school, it was a whole concept change on how schools were organized and what they looked like,” she said.

Before Glacier went up, students had several transitions during their K-12 education. Reducing the number of building transitions was a positive change, Schottle said.

From 1969 until 2007, Kalispell’s elementary students attended one of the district’s five elementary schools (Rankin Elementary School opened in 2018) through sixth grade. Seventh graders attended Linderman School (now Linderman Education Center) and eighth and ninth graders went to Kalispell Junior High, which was later changed to Kalispell Middle School.

Once Glacier opened, the seventh graders joined the sixth and eighth graders at the middle school. This freed up classrooms in the elementary school, allowing the district to offer full-day kindergarten. Linderman, in turn, became the district’s alternative high school.

“When we opened Glacier, we took the Band-Aid off a lot of things,” Langohr said.

DIVIDING STAFF, students (except the 2008 graduating class) and student-athletes was a time of trailblazing. Employees who moved from Flathead and the junior high to Glacier “took a big risk to go to a new high school when everything was an unknown,” Langohr said.

“They were pioneers willing to leave the safe shores of Flathead, or the junior high, to come to Glacier to band together and get it done,” Langohr said.

With the split, student opportunities doubled.

“Because Flathead was the largest high school in the state, it was sometimes difficult to give everyone a chance to participate in athletics and activities,” Schottle said, with sports, and some activities requiring tryouts.

That first year came with growing pains, however.

“You double the amount of opportunities but what’s likely to happen, and did for a while, after you divide your number of students you’re not as strong athletically or academically because you’re dividing your talent pool,” Schottle said.

The decision to keep the graduating senior class intact at Flathead added to the challenge.

“What was interesting when we had only freshman and juniors, right off the bat it was really tough with fall activities, especially football. We lost every single game of football,” Lahngohr said. “We weren’t even close. That’s where Glacier built its grit.”

“As odd as it sounds it’s the best thing to happen to us to get our foundation and the foundation was grit, grace and gratitude,” Lahngohr added. “I’ll tell you what, we learned all three in that first year, especially with our activity teams.”

TO ENSURE Flathead was not left out of the picture, money from the bonds went toward primarily renovating the front of the school by constructing the commons and cafeteria, along with other updates, such as to the gym.

“At initial renovation and expansion meetings the community stated very clearly, when we had listening sessions, that they wanted the process to be as equitable as possible and wanted everyone to have something new and updated in the process,” Schottle said.

Langohr, who was appointed as the planning principal and project manager, spent a year overseeing the process. She said the staff members, board trustees and community members who gave time to serving on a committees related to the construction project resulted in an outcome that “reflected what the community wanted.”

“There were three things we were committed to,” Langohr said. “One, that it came in under budget. That we really paid attention to cost. We value engineered what we could do to build a nice brick and mortar building.

“The second thing is that it was important we held to our timeline. We knew we wanted Glacier turned over to the community in June so teachers could move in and organize and be up and running by that fall 2007,” Langohr said. “So we could reassure kids they weren’t missing out on anything.”

The third priority was looking after the community.

“We knew our community was very, very loyal to Flathead,” Langohr said. “Some of these teachers had been teaching for 10 years in the same classroom and going to a new place to teach is hard. We made sure we spent a lot of time communicating with people.”

Both Langohr and Schottle expressed gratitude for the community and taxpayers for backing the project.

“In the end, it was truly amazing the way the community came together once they’d been able to be part of the planning committees, making that all happen was exceptional, and for all the smaller communities to come together,” Schottle said.