Copyright Slate

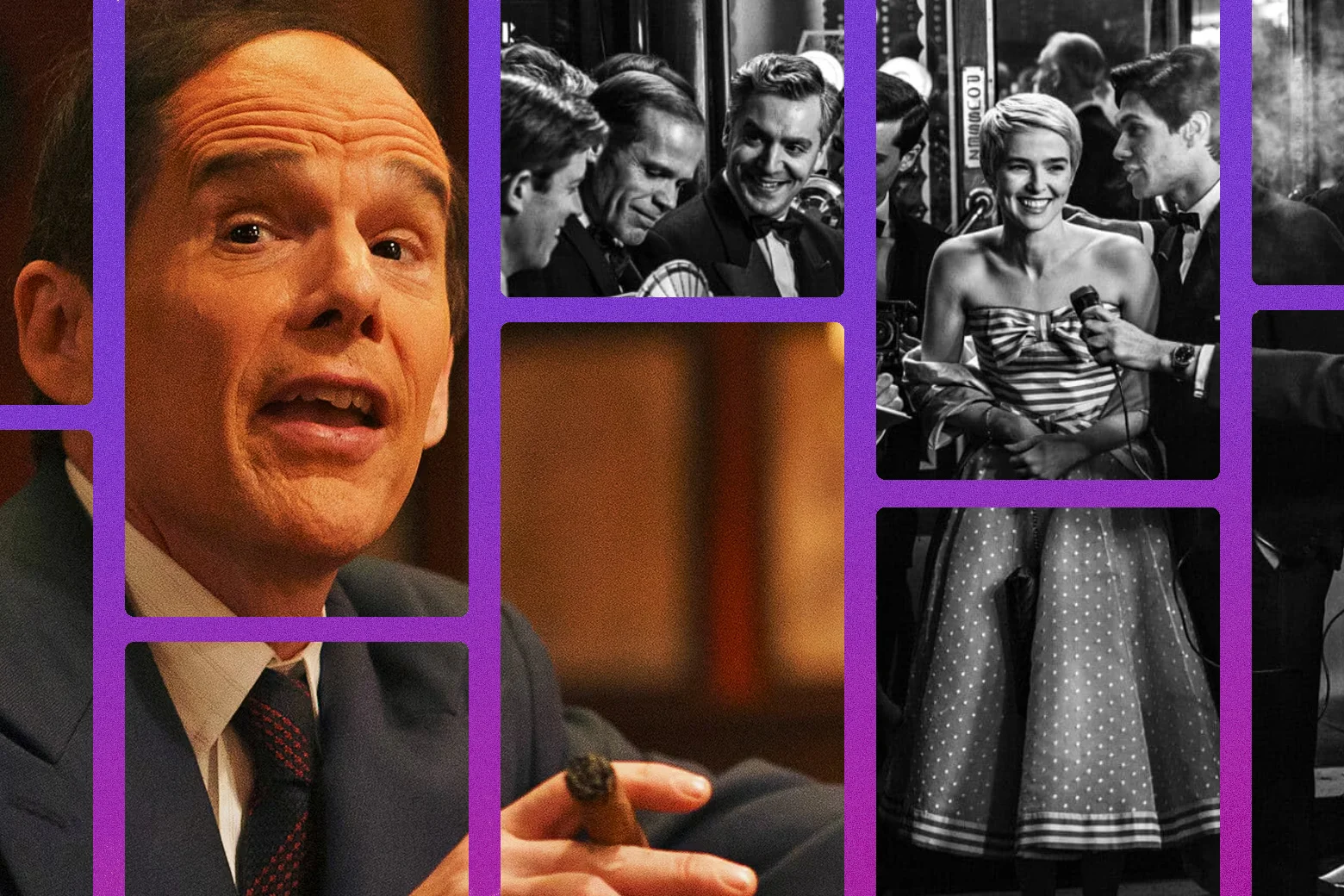

The built-in paradox of the artist biopic is that, with rare exceptions, any film that tries to represent the life and creative process of a great artist will necessarily result in a less brilliant work than its subject would themself have produced. Ray, for one, is a fine example of the musical biopic, with a galvanic lead performance from Jamie Foxx, but can it hold up to Ray Charles’ 1960 recording of “Georgia on My Mind”? Last year’s A Complete Unknown featured a superb Timothée Chalamet as the young Bob Dylan, but no one would call James Mangold’s well-observed portrait of a folk musician on the verge of a creative breakthrough the cinematic equivalent of a Dylan ballad like “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.” Every so often, a truly original filmmaker will tell the story of another artist’s life and creative process in such a way as to create a freestanding masterpiece: Andrei Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev, Max Ophüls’ Lola Montès, Mike Leigh’s Mr. Turner and Topsy-Turvy, Jane Campion’s Bright Star and An Angel at My Table (Leigh and Campion being among the rare directors to have pulled this feat off twice). But something about the biopic’s necessary subservience to the historical record of its subject’s life and work often consigns entries in this genre to middlebrow or even kitsch status. In two sprightly new films out this October, writer-director Richard Linklater has found an idiosyncratic way to escape this biopic trap. Blue Moon, about a single night late in the life of the great mid-20th-century lyricist Lorenz Hart, and Nouvelle Vague, about the making of Jean-Luc Godard’s 1960 debut feature Breathless, each proposes in its own way the notion of the biopic as an act of criticism. Linklater’s evident admiration for the work of these artists has led him to make two films that set out to show audiences not necessarily who Hart and Godard were as human beings (we never see either at home, for example) but why we should care about the work they made, those songs and movies that are still actively shaping how we see and hear our world, whether we’re aware of their influence or not. The films could be seen as contrapuntal companion pieces that play out their related themes in separate but complementary rhythms. Nouvelle Vague darts forward at the effervescent pace of the cultural youth movement it chronicles, while Blue Moon ambles and digresses, casting the occasional rueful backward glance at an earlier and more fulfilling time in its middle-aged hero’s declining career. The characters of Hart, as played by Linklater’s longtime creative collaborator Ethan Hawke, and Godard, as played by newcomer Guillaume Marbeck—a professional photographer making his first appearance in a feature film—have some important qualities in common. Distinct though their styles are, they share an irreverent wit and a keen awareness of their own outsider status in the entertainment industry. Both men display a chip-on-the-shoulder confidence that barely masks a deep insecurity. Both relate to their surroundings and to their work with an uneasy mix of romantic idealism and self-protective sarcasm. Above all, both are driven by the sense that the art form they love, and to which they each believe they have a unique contribution to make, is failing to live up to the standards they insist on holding it to. Hart’s introspective melancholy and Godard’s restless kineticism are presented as equally valid modes of approaching the creative process, one suited to youth, the other to age. Of the two movies, Blue Moon feels like the more major entry in the director’s filmography, if only because it marks a new epoch in his ever-evolving partnership with Hawke. For more than a decade, the two have been reading over and talking about the script by Robert Kaplow, a novelist and former high school English teacher whose book Me and Orson Welles Linklater adapted to the screen in 2008. When Linklater first brought the script to Hawke, they agreed the actor was too young to play the lyricist, who on the day the film is set—March 31, 1943, the date of the Broadway premiere of Oklahoma!—is 47 years old, and a particularly careworn and alcohol-soaked 47 at that. But even as Hawke was aging in front of the camera over the course of Linklater’s decades-sprawling Before trilogy and the even more time-bending, 12-years-in-the-making experiment Boyhood, the actor was growing both physically and artistically into the performer who could take on Lorenz Hart, the most transformative role of his career thus far. Even in the most demanding of Hawke’s performances—I’m thinking of his searing turn as a tormented priest in the great Paul Schrader drama First Reformed—we’re used to seeing the actor as some variation of himself: scruffy, earnest, somehow boyish even deep into adulthood, a slightly more grizzled version of the handsome leading man he played in Gen X comedies like Reality Bites or, yes, Before Sunrise. The character he inhabits here is a radical shift away from that territory. Hart was a tiny man, around 5 feet tall, and his self-consciousness about his height, his thinning hair, and his generally unprepossessing appearance permeates every moment of Hawke’s time on-screen. (Linklater, Hawke, and the crew worked with Latham Gaines, a friend and former collaborator of Hawke’s billed in the credits as the film’s “height wizard,” to create the illusion of Hart’s small stature using practical effects that included trenches dug into the soundstage.) Hart was also a gay man—albeit one who experienced painful crushes on women as well, and proposed marriage to three of them—at a time when queer desire had to be spoken of in code even in the milieu of New York musical theater. Hawke’s performance conveys all that: Hart’s discomfort in his own body, his internalized homophobia and alcoholic self-destructiveness, but also the deep joy he finds in language (he’s always pausing to note his approval of individual word choices, many of them his own), in music, and in all forms of beauty. Blue Moon takes place in a single location in just under two hours of real time; in essence, it’s the story of a man sitting in a bar (the venerable Broadway watering hole Sardi’s) over the course of one evening, alternately charming and boring whoever he encounters with a steady stream of observational chatter and self-deprecating wit. But Kaplow’s script neatly avoids both claustrophobia and staginess, dividing the story into three discrete acts. First, in a nearly empty bar, Hart puts on his one-man show for the bartender (Bobby Cannavale), the house pianist (Jonah Lees), and another bar patron (Patrick Kennedy), a quietly observant fellow who turns out to be the New Yorker essayist and children’s book author E.B. White. Then—after briefly greeting his latest object of unrequited longing, a Yale sophomore named Elizabeth (Margaret Qualley) who’s arrived to help set up the after-party for Oklahoma!’s opening night—Hart has an extended encounter with his longtime songwriting partner Richard Rodgers (Andrew Scott), fresh from the glowing reception of his first musical co-written with Oscar Hammerstein II (Simon Delaney). The audience, watching in 2025, knows that Rodgers and Hammerstein will go on to become the most successful musical-theater duo of the next half-century. Hart, too, with a clarity born of his own self-loathing, senses that his moment in the spotlight has passed. Hammerstein’s broader, more sentimental lyrics, with their “corn as high as an elephant’s eye”—a line from Oklahoma! that Hart quotes to White with a shudder—have picked up the baton from Hart’s intricate, internally rhymed lines (“I’m wild again / Beguiled again / A simpering, whimpering child again”). The melancholy urbanity that makes songs like “My Funny Valentine,” “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was,” and “Isn’t It Romantic?” now sound like timeless classics was precisely what made them seem dated at the height of the Second World War. In Blue Moon’s final act—though the three sections flow into each other seamlessly, with no clean breaks in between—Hart and his coed crush withdraw into the Sardi’s coatroom for a private moment that’s less romantic than it is conspiratorial. For me, this stretch was the weakest part of the movie, mainly because Qualley seems profoundly miscast in the role of Elizabeth (a character based on a real-life college student with whom Hart maintained a correspondence). Her character is meant to be 20 years old, with artistic ambitions but little experience; Qualley, on the other hand, is 31 years old, with all the poise of the gorgeous movie star she is. This isn’t exactly a critique of Qualley’s performance: I just wish that Linklater, who has often shown himself to be adept at casting unknown and sometimes nonprofessional actors in major roles (think of Ellar Coltrane, the unforgettable child-to-teenager star of Boyhood) had sought out a less famous face, someone who came across less as a sexy and self-possessed woman than as a brash and precocious but still-unformed girl. When Qualley’s Elizabeth entertains the enthralled Hart by recounting her botched hookup with an oafish frat boy, it’s hard to imagine the commanding young woman she presents as having such an abject sexual experience. Be that as it may, Hart’s age-inappropriate crush on Elizabeth is not reciprocated, remaining in the realm of idealized courtly love. Hart’s passing fixation on this particular young woman, we’re led to see, is just one symptom of the self-destructive romanticism that has also contributed to his alcoholism, an addiction that—as we know from the heartrending flash-forward with which the movie opens—will very soon put an end to both his songwriting career and his life. The conversation between youth and age is also a major theme in Nouvelle Vague, even though virtually every character in the movie is young; the figure who observes their antics from the wiser but sadder perspective of middle age is none other than the off-screen Linklater. (The script is by Holly Gent and Vincent Palmo, adapted and translated into French by Michèle Halberstadt and Laetitia Masson.) Indeed, the studiedly laconic Godard, whom we first catch sight of watching a movie in the black sunglasses he never removes, is ashamed to be the late bloomer in his cinephile circle, having not yet made a feature film at the advanced age of 28. Witnessing the success of his friend François Truffaut (Adrien Rouyard), with The 400 Blows, at the Cannes film festival—a trip he steals money from the Cahiers du Cinéma petty-cash box to make—the apparently unbothered but secretly competitive Godard vows to scare up the minimal budget needed to make a movie that, as he brashly assures his concerned producer Georges de Beauregard (Bruno Dreyfürst), will change the course of film history. True, Godard has no shooting script to speak of, asks his cameraman Raoul Coutard (Matthieu Penchinat) to use a camera so noisy it rules out the possibility of synced sound, and observes a work schedule so chaotic that the director sometimes sends his cast and crew home after getting just one shot, or blows off a whole day of filming to play pinball alone in a café. But the producers, like Godard’s initially dubious cast and crew, begin to see the method in this headstrong young man’s madness once he finally assembles the “girl and a gun” that, in his own formulation, are all that’s needed to make a movie. The filming of Breathless took place mainly in the streets of Paris, without permits from the city, in a guerrilla-style rush that lends the film its jagged, electric energy. What we see here are the moments just before and after Coutard’s noisy camera begins to roll, as stars Jean-Paul Belmondo (played by dead ringer Aubry Dullin) and Jean Seberg (marvelously embodied by Zoey Deutch) struggle to comprehend the demands of their mercurial director. Why does he want them to read long literary passages into the camera and re-create their favorite moments in Humphrey Bogart movies? Seberg in particular, fresh from working with the notoriously overbearing Otto Preminger, is unsettled by her new director’s lack of concern with such trifles as continuity editing and scripted dialogue. A late scene in which the crew shoots Breathless’ ending includes a sly speculation that the movie’s closing image emerged from a conflict between actress and director, with Seberg’s ambiguous improvised gesture winning the day over Godard’s more downbeat suggestion. Filmed in black and white in the old-fashioned 1:37 “Academy ratio,” with the atmosphere of mid-20th-century Paris impeccably re-created by means of too-subtle-to-spot digital effects, Nouvelle Vague is an hour-and-45-minute-long bagatelle that goes down as easy as a café crème at a standup counter, and provides a bigger burst of energy. Linklater has fun pastiching some of Godard’s signature stylistic techniques (the choppy edits, the direct-to-camera gaze), and the dialogue, all in French, pingpongs along with the deadpan rapidity of early French New Wave. A crabby critic might note that the dramatic action in Nouvelle Vague lacks meaningful conflict; after all, everyone watching in 2025 knows that Godard is indeed making a masterpiece that will change film history, so whatever confrontations he has with producers, cast, and crew along the way come off as fairly low-stakes squabbles. But Nouvelle Vague is less a dramatization of the act of shooting Breathless than it is a celebration of youthful cinematic ambition—the same divine madness that sent the 29-year-old Linklater on an equally permit-less journey through the streets of Austin to shoot his own medium-reinventing breakthrough movie Slacker. Nouvelle Vague is an affectionate portrait of the artist as a young nutjob with absolute faith in his vision, and an invitation for creators of all kinds to believe in their own similarly implausible dreams. To borrow a phrase from Lorenz Hart—one that would apply just as well to the movie Linklater made about and for him—it’s a funny valentine.