A team of scientists has pulled off a microscopic trick worthy of Houdini. In new research out today, they show it’s possible to create functional human egg cells from a person’s skin cells.

Researchers at Oregon Health & Science University led the study, published Tuesday in Nature Communications. Using a variety of techniques, they successfully fertilized eggs generated from skin cells, which then grew in the lab for several days. Though the findings are only a proof of concept for now, the method could someday provide a new way to treat infertility if fully worked out, the researchers say.

“[F]urther research is required to ensure efficacy and safety before future clinical applications,” they wrote in the paper.

Cell reprogramming

Millions of people worldwide are infertile, often due to dysfunctional gametes (eggs or sperm).

In vitro fertilization can help some couples successfully conceive, but not all, especially people who seem to have no remaining functional eggs. Scientists at OHSU and elsewhere have hypothesized that a person’s other cells can be reprogrammed into a functional egg or sperm cell using a method called in vitro gametogenesis (IVG). These newly formed gametes could then be used for fertilization as usual (some scientists are working on a different branch of IVG, attempting to create egg and sperm cells from stem cells).

The OHSU team and others have so far demonstrated that female IVG can be done with mice skin cells, but the new study appears to be the first to show that such a process is possible with human cells, too.

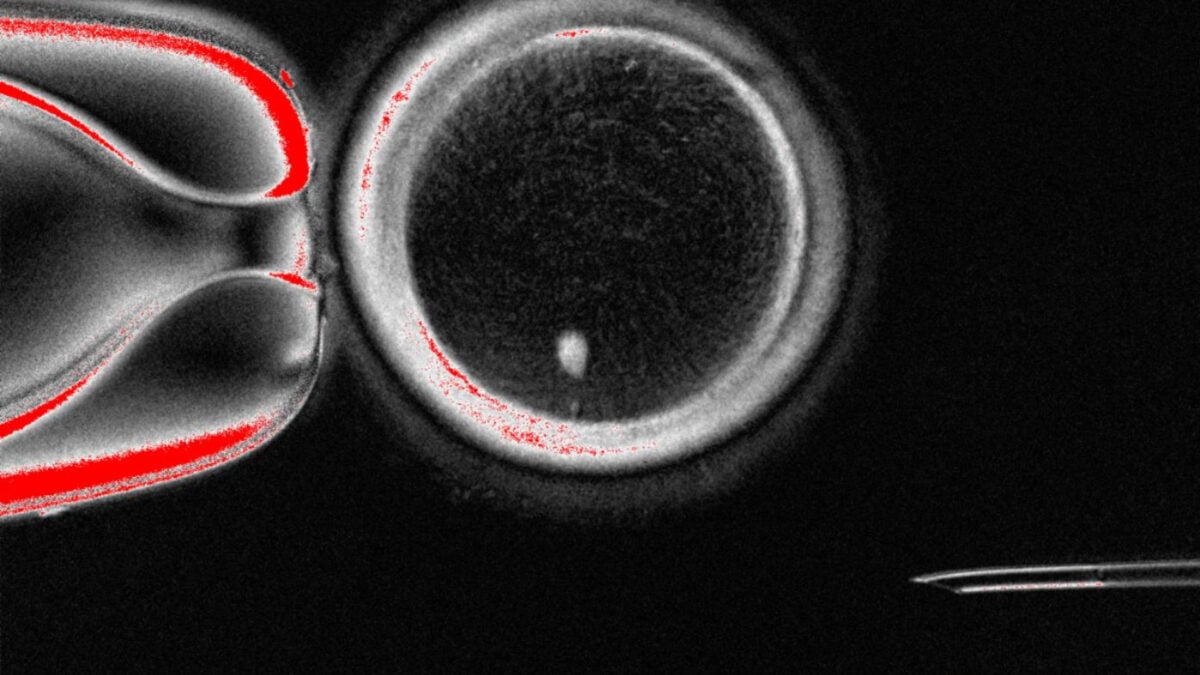

To create these eggs, the researchers replaced the nucleus of an egg cell with that of a skin cell—a method called somatic cell nuclear transfer. The method had previously been used to create cloned animals, such as Dolly the sheep.

They couldn’t stop there, however, since healthy eggs and sperm contain only one set of chromosomes, whereas other cells carry two. Thus, using the replacement eggs as-is for typical fertilization would result in zygotes—fertilized eggs that develop into embryos—with too many chromosomes.

To get around this hurdle, the researchers applied mitomeiosis, a technique intended to mimic the natural process of meiosis. This process helps turn cells with two sets of chromosomes into a sperm or egg cell carrying one set, discarding the spare sets of chromosomes.

They generated 82 functional eggs in total. Of these, 9% were successfully fertilized by sperm and developed into a blastocyst, the ball of cells that forms from a zygote about five days into fertilization. Researchers typically only study embryos in the lab until they reach the blastocyst stage, which is also when doctors usually implant an embryo created through IVF in someone’s uterus.

Much left to overcome

As impressive as the team’s feat was, they caution that the technique is still far from being medically useful.

In addition to the low fertilization rate, the surviving blastocysts had numerous chromosomal abnormalities. Further testing also found that while they were able to successfully reprogram egg cells with the correct number of chromosomes (23), these eggs likely had vital differences from naturally produced eggs.

The reprogrammed eggs didn’t undergo crossover recombination during meiosis, for instance. This is a process where a cell’s two sets of chromosomes from our mother’s and father’s sides are mixed together to form eggs and sperm that have one set of chromosomes with material from both parents (this helps ensure genetic diversity).

In other words, as things stand now, these eggs are unlikely to yield embryos that could successfully develop into a human fetus.

“While our study demonstrates the potential of mitomeiosis for in vitro gametogenesis, at this stage it remains just a proof of concept,” the authors wrote.

Still, the team’s work does bring them meaningfully closer to the goal of creating viable eggs from practically nothing. With enough time, research, and luck, their technique or something similar could allow some families to conceive children they otherwise couldn’t have.