Copyright Resilience

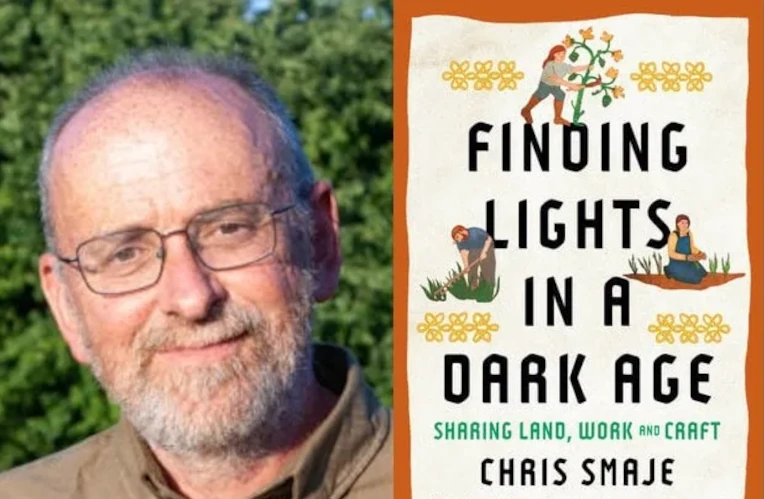

Chris Smaje on small farms, commoning, and a dark age future As part of the Sanctuary Series at Brimbscombe Mill in Stroud, Chik Shimasaki from GtC spoke to social scientist, writer and small-scale farmer Chris Smaje about his latest book, Finding Lights in a Dark Age. Making a case for A Small Farm Future in his first book, and rebutting ecomodernist solutions like vat-grown food in his second — Saying No to a Farm-free Future — , Chris Smaje continues the theme of reversing the move to the cities in favour of a more rural lifestyle for many. It will become inevitable, he argues, so we had better prepare for it consciously, rather than be forced to do it in a chaotic way. And we can learn to appreciate the benefits along the way. For the sake of brevity, we have taken key parts of the conversation and arranged them in a Q & A format. The text is lightly edited in places for clarity. Can you explain the thinking behind this third book? As various economic, political and biophysical chickens come home to roost, the state doubles down and becomes more and more authoritarian. But this can’t last forever. There’s always renewal, and it comes from the margins. With energy becoming less available and with increasing disorder, it will become more difficult for the state. It’s almost like a bargain is struck between states and citizens: we’ll provide health and social services, if you pay your taxes and don’t break the law too much. That, I think, is breaking down because it’s getting harder and harder for states to honour their side of the bargain. And that’s where people start innovating in all sorts of interesting ways, around the edges. It’s hard not to think of examples from the US at the moment with increasing polarisation and breakdown of any consensual politics at the centre. But within that context, people are starting to innovate solutions for themselves locally. We need to be thinking about the future and not assuming that existing patterns are going to persist. But obviously, I’m not clairvoyant and neither is anybody else. So I’m not predicting what will happen. I’m just saying, these are some of the trends that I perceive and I don’t think this is a time for false optimism, but to be asking what is the best way of amplifying and accentuating the positive. We might fall out once we start debating bigger, political issues or associations, but people are quite good at innovating practical ground-up local solutions and I think that’s where we need to be focusing in different ways. My focus has tended to be farming and the food system, but we need to do it in different ways, both materially, but also very importantly in relation to community building. Can you talk a little bit about the title: Finding Lights in a Dark Age? For the dark age context, I draw on the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre, a very interesting thinker who died a few months ago. One of his points was that the post-Roman dark age was a time when local elites stopped relying on Rome and centralised politics and started developing more local political solutions. People realised there was going to be collapse and crisis, and there wasn’t a simple answer to it. But people just innovated without necessarily knowing what they were doing. The story that’s come down to us is that this is a terrible thing. Dark ages are awful times, and that’s partly because the people who write the histories are the elites that lose out, whereas often enough, dark ages are times of relative well-being and freedom for ordinary people. When we look at the end of Roman rule in Britain, the evidence seems to point to ordinary people having better health status, being better fed, generally doing okay. So I play with that idea a bit. The problem we face now is that some former dark ages are not necessarily great models for the situation we’re in now, because in the past most ordinary people were relatively close to the land and were able to produce for their needs materially, and the centralised state was often an extractive apparatus that sat on top of that. In the book, you reference Adam Greenfield and his concept of ‘lifehouses’ — places for gathering and organising in emergencies. Applying this to more chronic crises, you say, farms might be the best lifehouses. With the current challenges to farming, do you think it will be possible to build them around small farms? It is going to happen by default anyway in relation to the crises and collapses that we’re looking at. It would be better if we managed it by design, in ways that are going to be less problematic. We live in a very urbanised world, and that is completely dependent on cheap abundant fossil energy. Some people think that we can transition out of that into equally cheap and abundant low-carbon energy. I don’t think that’s the case. And we’re looking at future ruralisation. That gets me into trouble a little bit, but I think it’s the reality. And I talk in the book about an idea I call open country. Where will people find sanctuary? Where will people move? Wherever they can find peace and prosperity. Historically, in the last couple of hundred years, to some extent, that has meant a movement from rural to urban areas. I think in the future, it will probably be the reverse of that. If you look more or less anywhere in the world, there tends to be a history of low energy input mixed farming that’s job rich, and is quite key to the local ecology. And we’ve temporarily bought ourselves out of that, over a century or two, with abundant cheap energy and global supply chains. And that’s been part of this push, this urbanisation, industrialisation — to get people out of farming. Farming is about the only sector where losing jobs from it is celebrated. For every other sector it’s, “great, we’ve created more jobs”, whereas we tend to celebrate losing jobs from farming. But the way that we’ve lost them is by using more agrochemicals, synthetic pesticides, herbicides, and essentially colonial expansion of agricultural frontiers in places where it is environmentally disastrous. So we need to draw back from that. We need to create more local jobs in farming. From your experience operating a farm, can you talk about the human relationships that need to be built to make farming as a community viable? It’s a complicated field. In one part of the book, I draw upon distributism. We’ve had this framing in modern times of left and right, state and market, but a lot of those debates are becoming less relevant. There are older traditions like distributism, that draws on Catholic social teaching and natural law theory. It is not really part of my intellectual background, but I’ve been drawn to it. One thing that I touch on in the book is that negotiating human relationships is always quite complicated and takes a lot of time. If I was a mainstream economist, I’d talk in terms of transaction costs. I’ve certainly experienced that in my own farming career. Much as I’m able to disagree with myself, there’s a lot of jobs I can just get on with and do myself, whereas once you start negotiating with other people, that takes time and effort. And very often, somebody carries the mental load for that. So it’s a matter of good design of systems where we do things at different levels of collectivity that are appropriate to the situation. We can really learn a lot from other societies that have had to figure out these long-term, face-to-face economic relationships, but we have to get over ourselves a bit and not assume they are yesterday’s societies and that that approach is backward looking. There’s an example in the book from Daniel Defoe’s tour through the whole island of Great Britain that he published in the 1720s, and the bit about Cheddar is really interesting. There’s a mix of private and collective property rights. Cows are individually owned by a household or family. They’re individually milked, and hay is made individually, but cows are grazed collectively. The milk is pooled together and made into cheese in a collective creamery, but then, the people have individual rights to do what they will with the cheese. That’s a great example of figuring out the point in the system when it makes sense to work together and when it’s easier to do things at a more distributed level. And that’s touching on the distributism theme that I mentioned. We talk about private property, but it can mean a whole bunch of different things. And we have this very extremist version of private property in modern capitalist society, which is partly that rights are exclusive. I mean, the way I frame it in the book is, ‘get off my land, you know you’re not allowed here. This is completely mine.’ And some rights are abusive – like: ‘it’s my land and I can do what I like with it’. And also accumulative, you can get bigger and bigger scale land owners, which is what happens. And increasingly, with abstract financial systems, you get more and more land in the hands of fewer and fewer people. And so we really do need to do away with that type of private property. The distributists’ argument is that we need to keep property ownership distributed. The knowledge that has been lost needs to be rediscovered, distributed and passed on. This is a complex process. You mentioned the possibility of guilds, and education as a vital part. Do you imagine a guild-like system to be the predominant way that knowledge is transferred, or are there other ways that you imagine? We need to be aware that a lot of what happens is going to emerge from crisis. We cannot avoid some of the biophysical and political economic problems that we’re facing. We don’t have mass technological or political solutions for them. This is the time to be experimenting. Guilds are interesting. They are the artisanal equivalent of an agricultural commons. And the idea is that skilled people are part of a guild that ensures that they are remunerated appropriately, but also that their work is of a high standard that serves the community. And this is one of the problems with the economistic mindset that we have now. Guilds can easily become a sort of trade union, pushing for its own interest. I’m not saying that the trade union movement in general does only that, of course – far from it. But that’s the difference. The guild is locally and community orientated, and contextual. There’s a lot to learn. There’s a lot that we’ve lost. And, again, part of the problem is that all this stuff about guilds and commons sounds very medieval and like turning the clock back. But that’s part of the problem that we’ve got into with the modern mindset, this whole notion of progress. A colleague of mine has just published a book called Progress, the History of Humanity’s Worst Idea. So often, talk about things being medieval is inherently pejorative. I think we need to get over that and just learn from models that work in appropriate contextual ways. But obviously, we’ve gained a huge amount of skills in modern societies. This is not an argument that we should abandon science and technology and not embrace newer knowledges, but it’s putting those knowledges properly to work in the social context that we’ll be facing in the future and not assuming that we will have endless cheap energy or endless supply chains that will provide for our needs. So it is about relearning at lots of levels how to do this stuff. Have you seen an increase in small mixed farms in recent years? Yes and no. A positive sign is that a lot more young people are interested in food, farming and environmental issues and are very energised, wanting to get into farming and the regenerative farming movement, and thinking more about circular economies and inputs and so on. Things have moved on, but one problem I talk about in the book is that we have this overfinancialised global system, that continuously frustrates. Property values, land prices are massively inflated. And that comes down to the fact that we’ve invented this symbolic system of money that has no real relation to local ecologies. So, there’s a lot of people with a lot of great ideas, but getting access to land is problematic. Land is an unusual commodity in many ways. A lot of people who are community minded and perhaps have access to some money are trying to use it to get hold of local land. Unfortunately, money tends to end up in the pockets of the land owners. This is a problem with our extremist form of private property. But there are things that are happening, and there is more interest in mixed farming, but it’s still not really there because of that over-financialisation and everything associated with the larger global food system and the cheap abundant energy and global supply chains and so on. What keeps you going? I just think people are really great at practical material problem-solving. It’s almost like the global news is designed to make us get angry at other people. But when you actually meet another person in the flesh, we’re always looking to connect and come together and solve problems. So what keeps me going? We’ve talked about some of these examples of commons and distributism and families and community connection. Viking society was fascinating and great if you were a Viking, but not so great if you were a victim of Viking predation. And in some ways that is the world we have inherited. We are still living in a Viking world. It’s a world of extreme violence, predatory, colonial extraction, extraction from the underlying ecology and extraction from other people, and we almost forget that or gloss around it. So, the idea of a dark age appealed to me because you can sort of play with it in those ways. That’s what keeps me going — the fact that the basics of this are not difficult. We can do it. And the fact that we’re here at all means that our ancestors did it. The difficulty is that we’ve boxed ourselves into a political and economic corner and lost touch with the ability to generate good livelihoods locally, ecologically. We don’t have simple answers where we can just say, right, ‘That’s what we need to do’. So we need to do things locally, individually, in community from the grassroots. And that’s what keeps me going.