Copyright asiasamachar

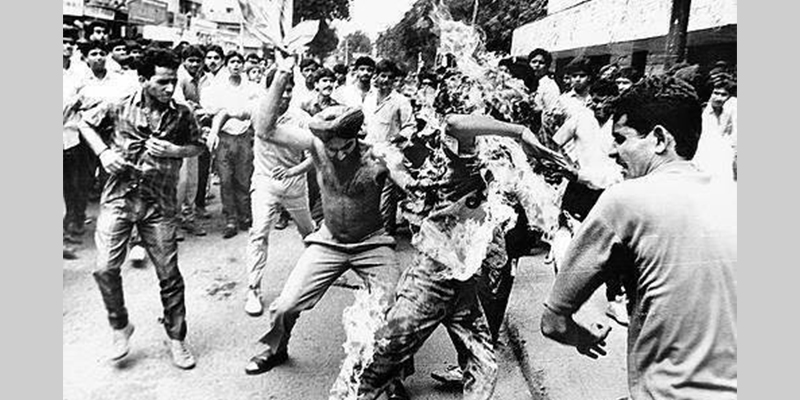

By Gurnam Singh | Opinion | On 24 November, the Delhi and central governments will roll out the red carpet for the 550th Shaheedi Divas of Guru Tegh Bahadur in the grounds of the world-famous Red Fort, a stone’s throw away from Chandani Chowk, where Guru Sahib, was beheaded by the then Mogul Emperor, Aurangzeb. No doubt we will witness a magnificent, state-sponsored spectacle: illuminated noisy processions, vibrant stage shows, vast gatherings, and the requisite security detail, all costing crores of rupees. It will be curated as a majestic, photogenic display of national unity and a safe affirmation of Guru Sahib and his unprecedented sacrifice. But only days before, from November 1 to 3, another anniversary will pass like a whisper in a storm: the 42nd remembrance of the 1984 anti-Sikh genocide. In those dark days, following the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, thousands of Sikh men, women and children were systematically hunted down and massacred in the streets of Delhi and other cities. For the survivors, the state’s silence is not merely deafening; it is a continued act of betrayal. As Harjit Singh, whose father was burnt alive in Trilokpuri, put it with heartbreaking clarity, “They are spending crores to light up Delhi for Guru Tegh Bahadur’s martyrdom, but they cannot light a single lamp for those who were burnt alive in these same streets.” Delhi’s hidden history of genocidal violence Sadly, the Sikh Genocide of 1984 in Delhi does not represent an isolated incident; it is a window into deeply contradictory history and nature of the city. The celebrated British chronicler of Indian history William Dalrymple observed that the “Partition was a total catastrophe for Delhi… Those who were left behind are in misery. Those who were uprooted are in misery. The Peace of Delhi is gone. Now it is all gone”. Dalrymple captures the contradictory nature of India more generally; a place of immense beauty and sacrifice on the one hand, but place that harbours a darker history of unimaginable violence and suffering. Today, behind the shiny cosmopolitan exterior, as it prepares to commemorate the 550th martyrdom anniversary of Guru Tegh Bahadur, Delhi remains perpetually suspended between hysteria and horror that encapsulates the contradiction at the heart of the city. This is the crux of the moral bankruptcy: The celebration of an ancient martyr is safe because it is unifying and apolitical, demanding accountability from no one alive today. The remembrance of 1984, however, is a direct threat. It risks implicating the modern political class and forces the inconvenient question: Where is the justice? Justice: A Political Commodity The narrative of state failure since 1984 is a monumental indictment. Decades have passed, from Ranganath Misra to Nanavati, commissions have sat, and mountains of testimony have been amassed, all pointing to the complicity of the Indian state and systemic failure to protect the innocent Sikh minority in Delhi. Yet, for all the evidence, we have witnessed only a handful of convictions. The deliberate slow-walking of justice has ensured that many alleged perpetrators have simply died before facing trial. SEE ALSO: The Truth of Guru Teg Bahadur Ji’s Martyrdom SEE ALSO: 1984: When Darbar Sahib became enemy territory Survivors still languish in resettlement colonies, struggling with trauma and neglect, while politicians invoke Sikh history as a mere ceremonial flourish. This neglect is compounded by the persistent, institutional refusal to call the events what they were: a genocide. The targeted, organised nature of the violence, coupled with clear state complicity, makes common characterisation of it as ਦੰਗੇ or ‘riots’ a complete obfuscation, designed to diminish the scale of the crime, blame the hired killers or ordinary people and avoid state complicity and international scrutiny. The evidence pointing towards leaders of the then ruling Congress Party, Sajjan Kumar, Jagdish Tytler, and the late H.K.L. Bhagat, is not mere historical conjecture; it is the accumulated record of multiple commissions. The state machinery, under their control, was either passive or actively abetted the mobs. While Sajjan Kumar’s 2018 conviction was a long-delayed drop of justice, the broader system that protected these men for decades remains intact. Successive Congress governments actively suppressed investigations and closed cases for “lack of evidence,” a failure that survivors rightly see as a fundamental assault on their humanity. The BJP’s Selective Weapon In recent years, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the BJP have leveraged the trauma of 1984 into a political cudgel, placing the entirety of the blame squarely on the Congress. They claim credit for reviving stalled cases and point to key convictions secured during their tenure as proof of justice delivered. For the BJP, the memory of 1984 is a potent tool for electoral mobilization, especially among Sikh voters, serving as a reminder of their political rival’s darkest hour. But this partisan narrative, like any political tool, has its own blind spots. While the bulk of the indictment rightly focuses on Congress-era leaders, the call for justice must be universal. As a 2002 Hindustan Times report revealed, even the Delhi Police registered cases against 49 individuals with BJP and RSS affiliations on charges of rioting, arson and attempted murder, based on victim affidavits. The fact that no prominent BJP or RSS leader has faced the same scrutiny or conviction as their Congress counterparts raises a critical question: Is the pursuit of justice a non-partisan moral imperative, or is it merely a political weapon to be deployed against opponents? When a government fails to vigorously pursue claims against its own associated individuals, it is not delivering justice; it is merely continuing the tradition of selective accountability. A City of Unhealed Wounds Delhi today lives in two registers of remembrance. The martyrdom of Guru Tegh Bahadur is staged with grandeur: illuminated arches, televised sermons, processions stretching across the capital. This commemoration is “safe” for the state; it offers a spectacle of national unity while conveniently serving electoral ends. In stark contrast, the memory of 1984 remains muted, almost invisible in public life. Survivors gather at gurdwaras or memorials in modest numbers, but there are no state-funded exhibitions, no grand vigils, and no official acknowledgement on a scale commensurate with the loss. This imbalance transforms memory into a political commodity. A 17th century martyrdom can be safely packaged as heritage, but the massacre of thousands of Sikhs in the 20th century is treated as a political liability. As the capital prepares to light up its boulevards to commemorate an ancient struggle, the shadowed alleyways where that freedom was brutally extinguished in 1984 remain unacknowledged, unhealed and fundamentally unresolved. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who chronicled the horrors of the Soviet gulags, offered a timeless warning: “The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor classes, nor political parties either—but right through every human heart.” In 1984, that line was decisively crossed by the state machinery, turning ordinary citizens into predators and the government into a killer. Time to Forgive and Forget? One of the narratives promoted by the Indian state, and the BJP in particular, is that Sikhs should “forgive and forget” the events of 1984, often shifting the blame for the Sikh Genocide onto the Congress Party. The BJP argues that the Congress is now politically irrelevant, portraying itself as a bhaivaal (ਭਾਈਵਾਲ)—a friend and partner of the Sikh community. This claim is reinforced through initiatives such as the annual Fateh Divas, commemorating the sacking of Delhi by the Khalsa Army under the command of Sikh Missaldars, Jassa Singh Ahluwalia, Jassa Singh Ramgarhia, and Baghel Singh, in 18th-century Punjab. Similarly, they point to the establishment of Bir Bal Divas that honours the martyrdom of Guru Gobind Singh’s four sons on a national scale. For many Sikhs, these commemorations are a source of pride. Yet, as Pav Singh observes in 1984: India’s Guilty Secret, “In a nation where the rich and powerful have the means to pervert and evade justice, there can be no closure for the victim.” The failure to deliver justice for the Sikh Genocide of November 1984 not only harms the victims but also undermines the foundations of Indian democracy. It sets a chilling precedent that systematic, targeted violence can be committed with impunity. Until the modern Indian state can confront its contemporary failures with the same moral scrutiny it applies to ancient tyrannies, Delhi will continue to embody a nation of dual histories: glittering festivals staged upon the ashes of death and destruction. For minorities in Delhi and across India, the end of celebrations does not bring peace but a return to persistent anxiety. As the political scientist and anthropologist Partha Chatterjee argues, the postcolonial Indian state retains the authoritarian and disciplinary structures of the colonial state, reproducing violence while presenting itself as democratic and developmental. Concluding thoughts On past form, there is little doubt that the Delhi and Indian government is expected to take credit for the 350th ਸ਼ਹੀਦੀ ਦਿਵਸ (martyrdom) of Guru Tegh Bahadur, portraying him as a saviour of Sanatan Dharma. On 24 November this year, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi steps up to the podium at Delhi’s Red Fort, he has an opportunity to signal a truly new India. No doubt, he will recount the supreme sacrifice of Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji and extol his virtues as ਹਿੰਦ ਦੀ ਚਾਦਰ (‘protector of Hindustan’). However, to be true to the teachings of Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji and worthy of the status of a great statesman, which he seeks to claim, Mr. Modi must also officially take this opportunity to recognise the November 1984 massacre of Sikhs, in Delhi and further afield. As well as declaring it as a genocide, he must take personal charge of prosecuting the culprits and ensure compensation for the victims within a defined timeline. Though Sikhs can, and should, never forget 1984, only when the Indian state acknowledges its guilt can the victims begin the process of genuine healing and forgiveness. And through the process, with the blessing of Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji, perhaps Delhi and India can contemplate escaping itself from its violent past and heralding a new hope for a democratic, inclusive and peaceful future. Gurnam Singh is an academic activist dedicated to human rights, liberty, equality, social and environmental justice. He is an Associate Professor of Sociology at University of Warwick, UK. He can be contacted at Gurnam.singh.1@warwick.ac.uk * This is the opinion of the writer and does not necessarily represent the views of Asia Samachar. RELATED STORY: Book Review: Digging out old records for the ‘true story’ of Guru Tegh Bahadur (Asia Samachar, 11 Nov 2021) ASIA SAMACHAR is an online newspaper for Sikhs / Punjabis in Southeast Asia and beyond. You can leave your comments at our website, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. We will delete comments we deem offensive or potentially libelous. You can reach us via WhatsApp +6017-335-1399 or email: asia.samachar@gmail.com. For obituary announcements, click here