Copyright The New York Times

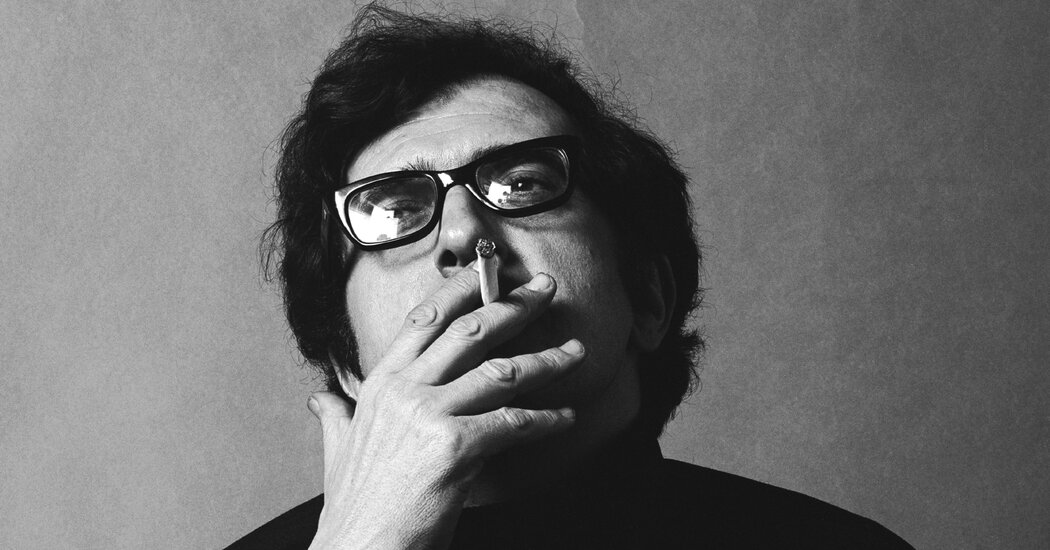

When William Schimmel was a student at the Juilliard School in the 1960s, he was put in an advanced music theory class with a teacher named Luciano Berio. Schimmel didn’t know much about him, except that he wore short European suits, smoked strong Gauloises cigarettes and made his students write up to eight fugues — about as hard as music theory homework gets — each week. On a classmate’s suggestion, Schimmel went to hear a performance of Berio’s “Sequenza III,” a revolutionary voice solo in which extramusical sounds like laughter, muttering and whimpering are treated with the same sophistication as fragments of clear melody. Schimmel realized that the person correcting his fugues was no buttoned-up theory teacher. Instead, he was one of the most original and renowned composers of his time. He’d even met Paul McCartney. He reminded Schimmel, now a composer and accordionist, of the actor Peter Sellers. “He moved in a very gestural way,” Schimmel said, “like his music.” Berio was born 100 years ago and died in 2003, but his music feels startlingly contemporary. It’s catholic, warm and complex, as well as inviting. “He always had a very musical feel to what he was doing,” said the composer Steve Reich, who studied with Berio. “You never got the feeling that this was a scientific exploration of sound.” Of the peers from his generation of European composers, avant-garde titans like Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen, “Berio’s is the music that’s most likely to last,” Reich said. Compared with Boulez or Stockhausen, Berio was a more grounded person and artist. He enjoyed good food and wine, and even in his 60s Bach’s music could reduce him to tears. Berio’s colleagues “were kind of beaming back to you from some other universe, but Berio is very much on planet Earth, and this is what makes him so special,” said the guitarist Eliot Fisk, to whom Berio dedicated “Sequenza XI.” Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times. Thank you for your patience while we verify access. Already a subscriber? Log in. Want all of The Times? Subscribe.