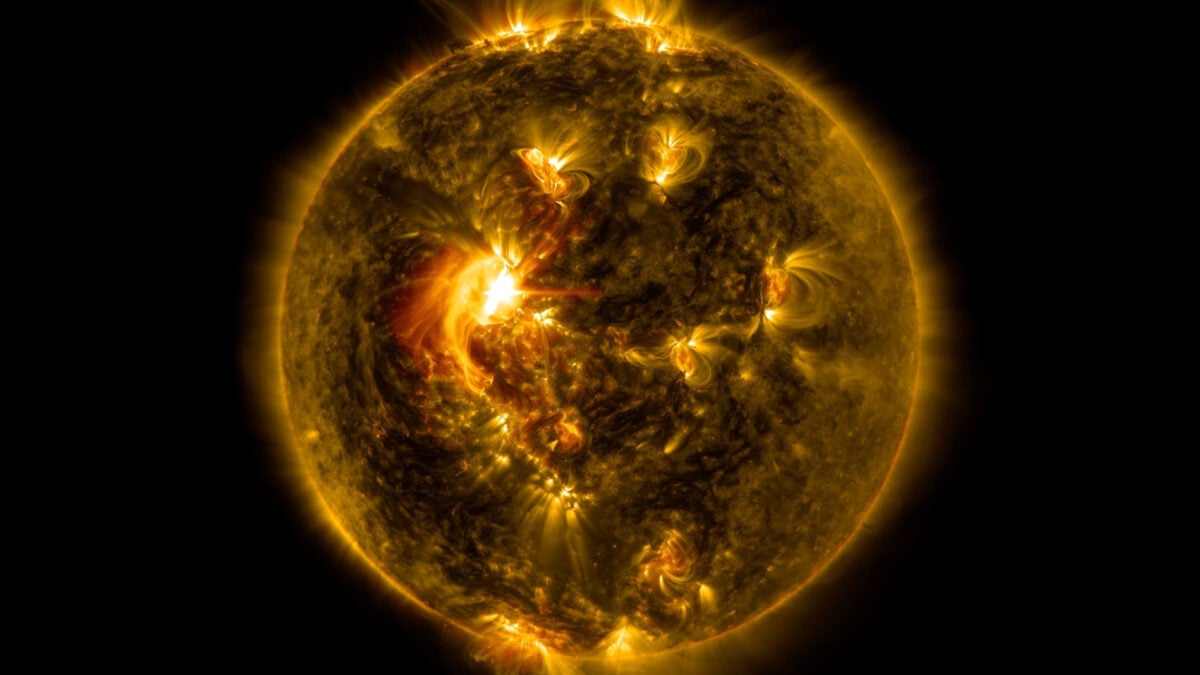

Autumn is the most dangerous season, as bears become highly active in search of food before winter hibernation. Japan is home to two species: the brown bear, or higuma, found in Hokkaido, and the Asiatic black bear, or tsukinowaguma, living in Honshu and Shikoku. A large brown bear can stand nearly three meters tall and is strong enough to break a horse’s neck with a single blow. They can also sprint 100 meters in as little as six seconds, while black bears cover the same distance in eight. The fatality rate for victims attacked by brown bears is 24 percent, compared with 2.3 percent for black bears.

Between April and August 2025, 69 people were injured or killed by bears, the same pace as two years ago, when an acorn shortage triggered the worst year on record. The Environment Ministry has confirmed new areas of bear habitation in surveys since 2018, with populations expanding across Japan except in Shikoku. Hokkaido’s brown bear population has more than doubled over the past 30 years, while black bears have expanded their range by 1.4 times. Today, Chiba Prefecture is the only part of Honshu without wild bears, while the species is extinct in Kyushu.

The surge in bear numbers is linked to shifts in human society. During the early 20th century, widespread hunting for pelts and gallbladders—used in traditional medicine—threatened extinction in some regions. But after a new protection framework was introduced in 1999, combined with population decline and abandoned farmland providing more food, bear populations rebounded rapidly. As their habitats extended closer to towns and villages, many bears lost their natural fear of humans and began appearing in residential areas as so-called “urban bears.”

Experts stress that both population management and deterrence measures are required. Mayumi Yokoyama, a professor at the University of Hyogo, points to the need to capture not only bears that enter towns but also those living near homes, in order to reduce overall numbers. At the same time, food sources must be managed: persimmons, garbage, and other attractants should be controlled, while electric fences should be installed around farmland.

In 2024, the government removed bears from its list of protected species and reclassified them as managed wildlife, alongside deer and wild boar. This shift allows more aggressive population control through concentrated hunting. Since September, municipalities have also been authorized to permit the use of hunting rifles in urban areas.

While bears have long been familiar figures in Japanese folklore, from legends of Kintaro wrestling a bear to tales of coexistence with nature, the growing frequency of encounters highlights the need for modern solutions. As experts warn, only by combining careful population management with preventive measures can people and bears continue to coexist in today’s Japan.

Source: TBS