Copyright news

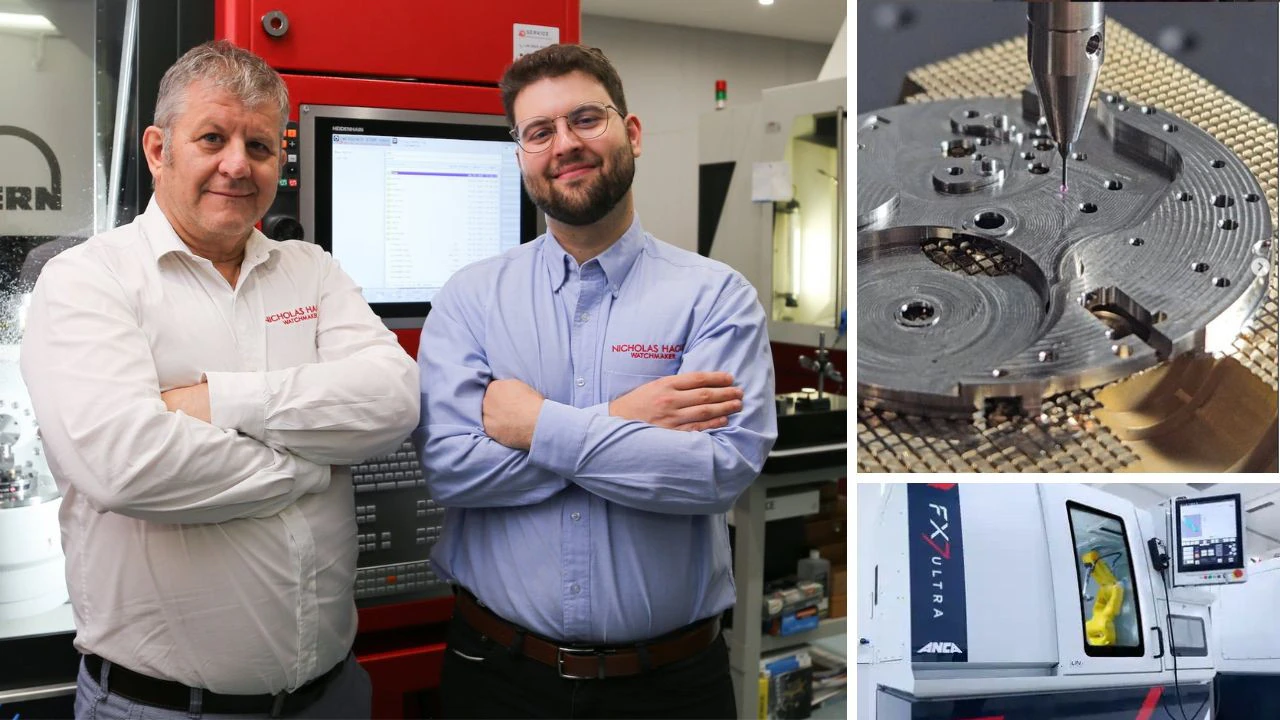

“You can fit 10 in your palm and buy a small car,” fourth-generation watchmaker and technical director at NH Micro Josh Hacko told news.com.au. He’s referring to a microfluidic mixing device – a specialised plastic component, about eight millimetres cubed, used in DNA genome sequencing machines. Each one, which takes an hour or so to make, costs around $1200. “We have the capacity to scale next year to about 500 units a year,” Mr Hacko said. As “Australian-made” faces an increasingly uncertain future, NH Micro is one of the country’s global success stories that highlights the opportunity for local manufacturing, despite its challenges. While Australia has long been the lucky country, that luck is running out – and saving our way of life means transforming into the “smart country”. But Aussie businesses need help. News Australia today launches the Back Australia campaign– an initiative that unites brands and people through a shared goal that matters deeply to all of us: building a prosperous future. “Right now, there’s a real groundswell of pride in supporting local,” Free News and Lifestyle editor-in-chief Mick Carroll said. “Australians are actively seeking out homegrown stories, products and people that reflect who we are.” The campaign will champion Australian businesses supporting local jobs, as well as celebrating Australian ingenuity. It will also examine the key issues impacting Aussie businesses and the reforms needed to allow them to prosper. ‘We have 15 years’ The Advanced Manufacturing Growth Centre’s (AMGC) managing director Dr Jens Goennemann does not mince words about the scope of the problem. “Doom and gloom or bright spots … the truth is probably somewhere in the middle because there are opportunities, but if you also don’t speak about the challenges we have, nothing will change the trajectory – and the trajectory is going down,” Dr Goennemann told news.com.au. “Australia is an amazing country. We have it too easy. “We lack the sense of urgency that what makes us so rich and liveable, mainly commodities, that this is a runway which comes to its end. So we need to start looking at alternatives when nobody buys our coal or gas anymore. If we don’t do that we do a disservice and leave the joint worse off for our children than we found it.” Dr Goennemann, who formerly led aerospace giant Airbus’s Australian operations, warned Australia was lagging dangerously behind similarly sized, high-wage, developed economies like Japan, Austria and Sweden. “These are all high-cost countries which are capable of making things, and we are not,” he said. “We rank at number 105 in the world in economic complexity. And the urgency of transforming Australia from the lucky country that we are into a smart country, starts with the realisation that if we are not able to make something here and find a customer, ideally globally, the country we are living in … will not be the same in 20 years.” Dr Goennemann believes the end of that runway is fast approaching. “I would think we have maybe 15 years,” he said. “It sounds long, but in order to build the capability … if you convince young people to take up a role, educate them, have them gain some experience, before we even have the workforce the decade is gone. So we need to do something now.” Of Australia’s roughly 47,000 manufacturers, 90 per cent employ fewer than 20 people. AMGC blames this missing middle of medium-sized companies on the nation’s lack of focus on commercialisation and scaling of goods and services. It’s so difficult in Australia to scale a business from small to medium and then onto large that the country has lost many of its most promising manufacturers abroad. “We need to focus on the areas of strength, focus on the small companies who are very capable and give the best of them a leg up to help them to scale and build medium-sized companies,” Dr Goennemann said. Part of the shift will mean changing perception about manufacturing itself – away from politicians in high-vis vests on shop floors during election campaigns. Production, which employs less than half of the manufacturing workforce, is “probably the least competitive and least value-adding” step, especially in a high-cost country, Dr Goennemann notes. Australia must embrace the entire chain – starting with research and development, design and logistics, and later distribution, sale and services. It will also mean less focus on finished goods, which make for nice photo ops when they roll out of the factory, but only account for 30 per cent of global trade. The other 70 per cent are intermediate goods – widgets, materials and components that “nobody has ever heard of” but play an essential role in global value chains. Work smarter Australian businesses face many challenges, but number one is high costs – chiefly energy. Meanwhile, lack of policy certainty stifles investment and long-term planning, red tape strangles productivity, and despite programs like Labor’s $23 billion Future Made in Australia or the $15 billion National Reconstruction Fund, critics argue the money doesn’t go where it could really make a difference. “If I look at our European friends, the policy blunders they have made in the last number of years where ideology was driving a lot of the policymaking, for example in energy, has really hurt manufacturers and I fear we are making similar mistakes here,” chief executive of Melbourne’s ANCA Group Martin Ripple said. Cheap power, which underpinned decades of Australian manufacturing from cars and tyres to textiles and steel, is now a distant memory. Since 2000, electricity prices have increased by 206 per cent and gas prices have increased by 334 per cent, far outpacing overall inflation rate. While thousands of businesses have hit the rocks, many have learnt to adapt and thrive. And they all say the same thing – we can’t compete on cost, so we have to build better products. Watch aficionados may be familiar with Nicholas Hacko Watchmaker (NHW), the family-owned business which has been making high-quality precision timepieces in Sydney since 2016 – the country’s only local manufacturer. Lesser known to the general public is NH Micro, which sprung from the watchmaker’s vertically integrated model, having been forced by a Swiss parts embargo to build its own from scratch Down Under. Today NH Micro has exploded to become one of the world’s leading precision parts manufacturers. “Six years ago we started to get approached by parallel precision industries outside the watchmaking sector to manufacture their very complex, precise mechanical components,” Nicholas Hacko’s son Josh, who serves as technical director for both companies, said. “That then transitioned into a fully fledged business – more than three quarters of our revenue comes from this side hustle.” NH Micro now supplies “the largest space companies in the world, the largest quantum computing companies in the world, the largest medical device manufacturers”. NH Micro’s “ultra high-demand” components are found in pacemakers, in Cochlear implants, in satellites for internet communication – and pretty soon, on the moon. Can’t compete on cost ANCA Group is another Aussie success story – a manufacturer of manufacturing. The 50-year-old company is one of the world’s leading makers of CNC grinding machines – exporting 99 per cent of its products to more than 45 countries, with clients including Airbus, Apple and major car manufacturers. “We like to say that every high precision part in the world is somewhat touched by an ANCA tool,” CEO Mr Ripple said. “Wherever metal parts are cut, drilled, milled, chamfered, ANCA has been somewhat involved. We believe 1.2 billion tools have been made on our machines over the years. “Those tools work turbine blades, they are used for iPhones, laptops, they make orthopaedic parts such as knee replacements,” he said. At the time ANCA entered the market, for a customer to buy a five-tonne CNC machine out of Australia “would have been a crazy decision”. “So we had to be several years ahead of our competition by having the best machines, the most reliable, the most precise in the market,” Mr Ripple said. REDARC chief executive Anthony Kittel purchased the Adelaide business in 1997 when it was a still a small eight-person cottage industry supplier of power products for the local automotive and trucking industry. Today REDARC employs 400 people and is a global leader in rugged, advanced electronics systems built to withstand harsh conditions, exporting to 38 countries across new sectors including 4x4, off-grid, mining, defence and space. When Mr Kittel took over, the business was bringing in revenue of less than $1 million – today it’s more than $150 million. “[Our success] comes from solving the customer need and developing a high-quality product people are prepared to pay a premium for,” Mr Kittel said. “One that doesn’t fail, that’s guaranteed to survive the journey if you’re driving to the Simpson Desert, Cape York or Broome or overlanding in the US – extreme temperatures, vibration, dust, moisture, water. “The second side of it is by doing smart design and smart manufacturing, making sure we can keep our manufacturing costs as low as possible without impacting on quality – so automation, techniques called design for manufacture where you want smart designs that a robot can assemble.” Mr Kittel said a key driver of REDARC’s success is its heavy investment in research and development. Every year since 2002, the company has invested 15 per cent of total sales revenue back into research and development, growing from one design engineer to around 140 in that time. ‘Adult in the room’ For Mr Kittel, red tape is one of his biggest headaches. “The compliance side of things is getting more and more bureaucratic,” he said. “The red tape around reporting on a whole bunch of different things as a business, we have to almost employ people (just to fill in forms).” Mr Ripple estimates the “never-ending additional regulatory burden” has added 5-6 per cent to ANCA’s costs over the past decade. “You’re coming to a point where it becomes less and less attractive to do business in Australia,” he said. From REDARC’s perspective, Mr Kittel would also like to see better tax incentives for research and development – and for Prime Minister Anthony Albanese to strike a deal with Donald Trump on tariffs. “We’ve had really good growth in the US, working hard for so many years,” Mr Kittel said. “Suddenly there’s 10 per cent and even 25 per cent on automotive parts, or 50 per cent with anything metal in it. It’s just astounding. It’s like putting a pin in the balloon.” This article is part of the Back Australia series, which was supported by Australian Made Campaign, Harvey Norman, Westpac, Bunnings, Coles, TechnologyOne, REA Group, Cadbury, R.M.Williams, Qantas, Vodafone and BHP.