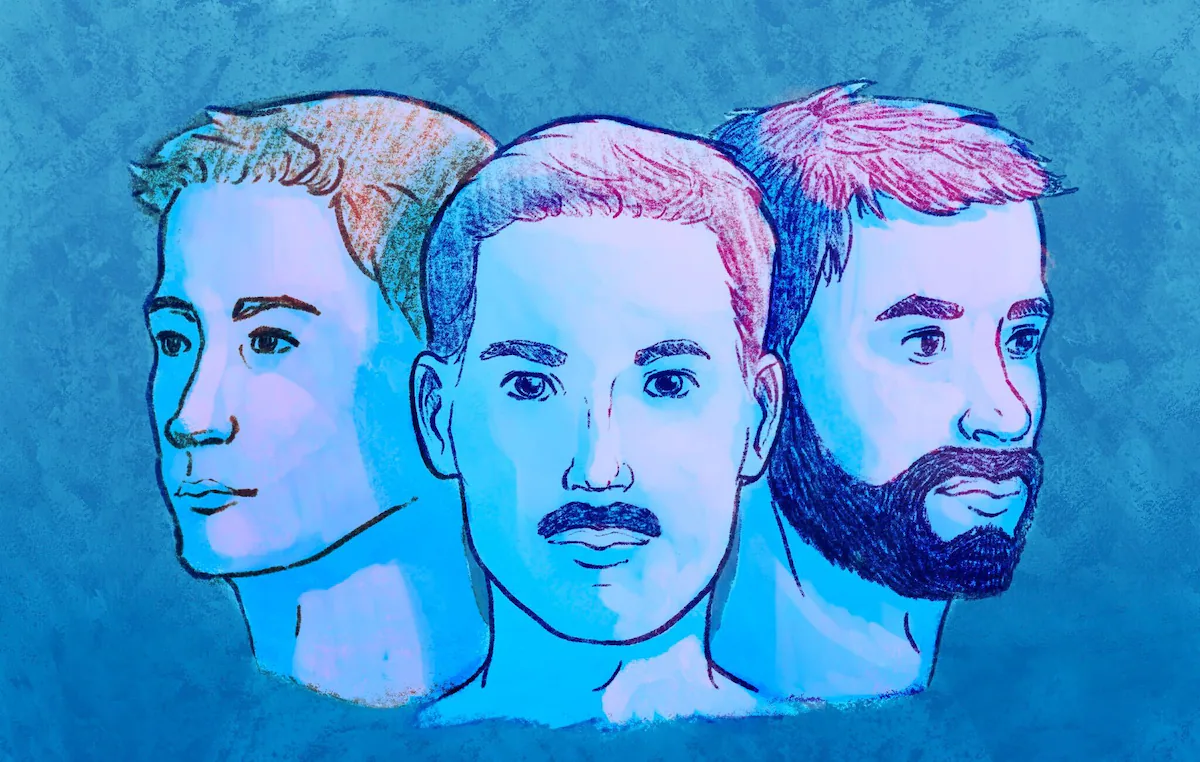

At Brigham Young University, plenty of male students pay lip service to the school’s clean-shaven image.

By sporting mustaches.

It turns out that the flagship university of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints — whose Honor Code famously bars beards — does permit “neatly trimmed” mustaches.

Consequently, a tidy stache is relatively common for Cougar men on campus.

BYU student Matt Curtis recently joined the mustachioed ranks, explaining that he grew facial hair just to see if he could.

“It’s a classic,” Curtis said. “It’s a staple of a Provo boy.”

But what about the wider prohibition on whiskers? Is it needed? Could it ever end?

“There’s not really a religious reason to not have facial hair,” Curtis said. “It’s a branding thing. BYU is the image of the church in a lot of ways.”

How the beard ban began

Historian, author and BYU alum Benjamin Park explained that the beard ban was rooted in a historical moment and that the university has not let go since.

The proscription traces its genesis to the 1960s, when beards were viewed as a symbol of anti-war, anti-establishment rebellion. It’s not a principle in the church — the school’s namesake wore a prominent beard, after all, as did seven of the church’s first eight presidents — but rather a policy at the school.

“This isn’t an eternal rule. This isn’t a doctrine. This is a practice,” Park said. “It’s rooted in a past time that I think we should be able to move beyond.”

The scholar also referred to the ban as a “remnant,” a symbol of BYU trying to separate itself from hippie culture but now ingrained as part of its identity.

It’s a standard, though, that female student Dara Layton supports, saying the restriction makes her male classmates more presentable.

“I like a clean-shaven guy,” Layton said. “BYU is just helping the men out.”

If students feel passionately about growing facial hair, she said, they can do so at another university.

Students “know all of the dress and grooming standards that (they) have to follow in advance,” Layton added, noting that they voluntarily agreed to abide by them.

Still, more than a few BYU students, faculty and alumni argue it’s time to whack the beard ban — especially since today’s scruffy style is seen as more hip than hippie.

The push to trim the ban

A Change.org petition launched several years ago to “Bring Back the Beard” has drawn nearly 2,500 signatures.

In a 2023 readers’ forum in BYU’s newspaper, The Daily Universe, contributor Brady Bowerbank called defending the ban “shallow and un-Christlike.”

Bowerbank pointed to senior apostle Dallin H, Oaks, who, when he was BYU president in 1971, labeled the school’s rules against beards and long hair “contemporary and pragmatic.”

“They are responsive to conditions and attitudes in our own society at this particular point in time,” said Oaks, who is next in line to lead the global church. “… The rules are subject to change, and I would be surprised if they were not changed at some time in the future.”

Bowerbank insisted that the future is now. He called on the university to rethink why the ban was adopted in the first place, saying the school should “do away with arbitrary, outdated, silly rules that serve only to distract from BYU’s mission.”

How to have a beard now at BYU

As with most rules, there are exceptions and exemptions.

With school approval, students can embark on a lengthy journey to obtain what is known as a “beard card.” This form of identification allows students to grow a coveted BYU beard while attending classes on campus.

According to the Honor Code’s website, there are three circumstances in which a student can obtain this waiver: medical, theatrical and religious.

Students may petition for exemptions if they are working on a production for the church or theater department that requires whiskers or if they belong to a faith — such as Sikhism, Islam or some branches of Judaism — that mandates or prioritizes facial hair.

Nefi Treviño, a former BYU student, received a theatrical exemption while working on the church’s “Book of Mormon Videos,” which depict events in the faith’s signature scripture.

He said that while he knows why BYU targeted beards, it now seems outdated to most students.

“It already has changed a lot,” Treviño said. “Before, people couldn’t even go to the testing center (with facial hair).”

Curtis said the rule is not enforced consistently, saying many students have facial hair in the classroom and then shave before taking an exam at the testing center.

“Why are we regulating it in the testing center and not in the classrooms?” Curtis asked. “If they’re not going to have it, they should not have it.”

Who signs off on a medical exemption?

Receiving a medical pass seems to be the most challenging of the three exemptions since not all skin ailments are treated equally.

Aside from serious injuries that prevent shaving, pseudofolliculitis barbae is the lone medical condition for which a beard waiver can be secured.

With this condition, shaving causes inflammation and red bumps to appear on the skin. At BYU, it is not enough to have any doctor attest to a student having this affliction. The student instead must be diagnosed by a physician at the school’s Student Health Center to receive consideration for a waiver.

And for the diagnosis to be valid, the condition must be “present and visible” regardless of the student’s medical history.

Curtis and other students are optimistic such hair-splitting soon will no longer be necessary, especially after the Church Educational System standardized guidelines in 2023 across all BYU campuses.

Other changes may be forthcoming, too. The Honor Code states, for instance, that clothes should be “modest in fit and style.”

“Dressing in a way that would cover the temple garment,” it advises, “is a good guideline.”

With sleeveless garments coming soon to the U.S., well, the amount of skin students need to cover may shrink.

— Tribune editor David Noyce contributed to this story.