In the series, Prospects for Degrowth

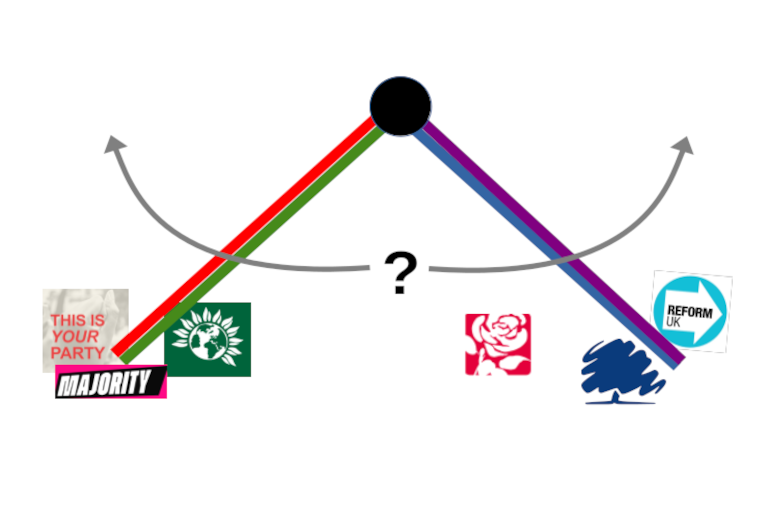

The last few weeks have seen two opposing developments in British politics, both in the context of the Starmer Labour government and its failure to address the real issues facing people and planet.

On the one hand we have seen the continuing rise of the far right Reform UK party, which has a number of fascist characteristics, aided by positive publicity, not only in the right wing press and the dark places of social media, but also by the BBC. This spectre is at one with similar demons rampaging across much of the world, most notably in the USA (with Trump implementing the Heritage foundation’s fascistic Project 2025) and in a number of European nations (Italy, Poland, and the test bed Hungary), Latin America (but not the big players Brazil and Mexico), and elsewhere. If that was bad enough, an emboldened ultra far right in the form of outright fascist and neo-Nazi groups is spreading their hatred and pulling in sections of the disaffected and ignored population, as at the so called Free Speech rally in London on 13 September. This rightward shift is dragging the two historically major parties, the Tories and Labour seemingly ever rightwards too, as they try, in vain, to mimic the appeal of the far right to those who have been impoverished under four decades of capitalism’s neoliberal iteration.

More hopefully, there have been two developments on the left. Firstly, the Green Party has elected a new leadership team, which seeks to replace Labour and take the fight to Reform, with an eco-populist platform. With this there has been a surge in numbers, building on recent electoral success, locally and nationally, and from the move of many former Labour Party members into the party. Secondly, the former Labour MPs Jeremy Corbyn and Zarah Sultana announced that they are launching a new left party, provisionally called Your Party. This has received widespread support in the form of thousands signing up as interested in being part of the project, although an inept web presence, internal disagreements on control and internal democracy, and a squandering of the immense wave of goodwill from supporters, have already cast serious doubts about the project. In both cases, there has been an emphasis on mobilising, not just in and around representative democracy but in and with radical social movements. In both cases key issues have been opposition to austerity and to accommodation with Reform’s racist anti-migrant agenda, together with outrage at the Starmer government’s collusion with the Gaza genocide.

But what about the real challenge?

However, there is a problem. Let me introduce it with a short digression. While daily lived struggles (under austerity and the consequences of global conflicts, two of the concerns driving these two left developments) are in the forefront, there is a more fundamental issue, which is actually driving both. That has several names, including global overshoot, the great unravelling, the climate and biodiversity emergencies, the crossing of planetary boundaries and the energy crisis. However, it is the scale of the material economy, far exceeding the capacity of the earth’s geophysical and ecological systems to sustain it, that is both the bigger threat to human lives and livelihoods, and the fundamental cause of most of the other problems (that and capitalism’s inescapable pursuit of profit, “accumulate accumulate!”). The only way out of this is a radical but equitable downscaling of material and energy flows – whether we are talking of food, energy or manufactured goods, these are the chains from extraction, through processing and distribution to manufacture and deployment, and ultimately disposal as waste. That is the agenda with various names but best called degrowth, since that names and problematises the key issue and does not allow dilution and co-optation. The remedy can’t be mere tinkering by adding a few ameliorative policies (job guarantee or universal basic income, monetary reform).

The problem is that neither of these British left alternatives appears to be sufficiently facing up to this fundamental issue (it goes without saying that the right isn’t!).

In the information about Your Party’s platform, which is admittedly still limited given that the party has yet to be formed and to formulate policy, there is no mention of this fundamental question. There is a passing mention of opposing the fossil fuel companies in the launching Statement, but that is all: nothing in interviews with either Zarah Sultana or Jeremy Corbyn. Majority, the grouping launched by Jamie Driscoll in the North East does put climate further up the agenda in its opening statement (which is similarly sketchy for the same reasons). Zarah Sultana was at their big event in September, and it seems likely there’ll be a merger, or federation at some point. Majority is some way ahead of YP in its development.

As for the new Green leadership, there is little in leader Zack Polanski’s successful pitch that indicates a commitment to degrowth (here I’ve linked the public version of his candidature statement – the one on the members’ section of the Green Party website is little different). Certainly he gives more mention to environmental justice and some of the key environmental issues than do the Your Party duo, but there is little evidence of depth, as some dissident Greens have noted. In an interview as leader, he did note that GDP is a bad measure (Green Party policy) and said he didn’t mind things growing so long as it is within environmental limits (which is fine but doesn’t go far enough in addressing the need to reverse overshoot by an overall reduction in the material economy).

There are two deputy leaders, both with good political outlooks. Mothin Ali does make a strong statement and mentions teaching permaculture, but, at least in his candidate statement, he doesn’t really link the insights from that discipline to political ecology and economy. Rachel Millward doesn’t mention the fundamental overshoot problems either, although again she has clear interests in related questions. Turning to the Green Party’s policies, as agreed by the membership, there is a good basis in the Philosophical Basis, which is supposed to underpin the Policies for a Sustainable Society. Some examples,

A system based on inequality and exploitation is threatening the future of the planet on which we depend, and encouraging reckless and environmentally damaging consumerism.

A world based on cooperation and democracy would prioritise the many, not the few, and would not risk the planet’s future with environmental destruction and unsustainable consumption.

Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, society has expected continual increases in material affluence for the people of the world, and has therefore relentlessly pursued the goal of economic growth.

We cannot go on indefinitely exploiting and wasting the natural resources of a finite world. If humans continue to promote policies which require the unlimited consumption of raw materials, it will lead not to more riches, even for the few, but poverty for all.

Conventional politics divides humans from nature and the individual from society. The rejection of this way of seeing the world is fundamental to Green philosophy. Rather than set them against each other, the Green Party seeks healthy interdependence of individual, nature and society.

Our survival depends upon the continued survival of all the ecosystems which evolved before us. The Green Party therefore sees humanity as necessarily a dependent part of the natural environment. Human activity has caused widespread and rapid damage to the environment and this is now threatening our future survival. Political objectives should accept our dependence, not seek to transgress it.

Western society has seen nature as valuable only in so far as it is useful to humans. Where human “development” has irreparably damaged the ecosystem, species have been driven to extinction, and the land is as useless for human purposes as it is for other species.

The central integrating principle underlying all Green Party policies is that all human activities must be indefinitely sustainable. They must neither use resources faster than they can be replaced, nor create effects or products which cannot be assimilated indefinitely by the environment.

There is not actually a statement that to fulfil these there must be a contraction of material economic activity, nor is there actually the use of terms like overshoot, degrowth, or even Limits to Growth, but the basis is there. Unfortunately, this is not well reflected in the main policy statement, and the manifesto at the last election barely approached the fundamentals, focusing instead on sound-bite slogans such as,

A £40bn investment per year in the shift to a green economy over the course of the next Parliament.

A carbon tax to drive fossil fuels out of our economy and raise money to invest in the green transition.

Bringing the railways, water companies and the Big 5 retail energy companies into public ownership. And

A share of community ownership in local sustainable energy infrastructure such as wind farms.

On energy, there were proposals on increasing renewables and phasing out fossil fuels but no mention of the overall energy crisis and the need for a rapid energy descent.

There is nothing wrong with much of this, in itself, but it is piecemeal and fails to level honestly with the public about the scale of the existential ecological crisis and the drastic measures, an Emergency Brake and a Plan for Reconstruction, (set out, for example in the Degrowth UK publication Getting Real) that are so urgently required.

I could go on, but the point is made. Neither the embryonic Your Party, nor even the Green Party, provide evidence that their approach, extant or emerging, at this point in time, is adequate to the scale of the existential crisis facing humanity. This could change, and it should be a focus of the small degrowth movement in these islands (where regional parties like Majority, Plaid Cymru and the SDLP, if not the SNP, are also potentially open to degrowth thinking). Again, it is important to stress that both parties aim for policy to be made by the membership, so that is where degrowthers need to get involved, in either formation: the path will not be easy. There will be green growthers and possibly ecomodernists in both camps, so our strategies, arguments and tactics need to be sound.

What might it look like if the circle were squared to make populist ecosocialist politics into a realpolitic of degrowth? The connection is in the opposition and seeking of alternatives to the capitalist accumulation regime, which turns everything into a process for value extraction and profit-making, colonising government to pass laws and enact policies that facilitate this. This is the root of both economic growth and overshoot and the impoverishment of the majority. However, on this it is worth recognising with John Bellamy Foster, in his piece on the ruling class and the State and its implications for political action, that “No political regime in a capitalist system can survive unless it serves the interests of profit and capital accumulation, an ever-present reality facing all political actors.” That means a revolutionary strategy, by which I don’t mean storming the Winter Palace, or its equivalent (just now anyway), but am referring to an older and more fundamental sense of ‘revolutionary’, a strategy that is not merely reformist or aiming to manage the toxic capitalist political economy more humanely, more ecologically safely. The limits to that approach in the present deep pancrisis would derail it, and the ruling class won’t tolerate it, as we saw when Corbyn’s Labour Party looked like it might implement a left reformist programme. So, on this both the newest left developments are correct, it will be necessary to combine a (revolutionary) social movement and class-based mobilisation with the judicious, critical use of the spaces that liberal democracy ‘kindly’ affords.

Here, perhaps is the secret to also countering the far right, not with ameliorative green growthism but with radical, redistributive, anti-commodity leftism – recovering that underground tradition of socialism that starts from a critique of capitalism’s turning everything into a commodity, and instead focusing on what we all need to lead a decent dignified life, within safe limits.