Copyright jerseyeveningpost

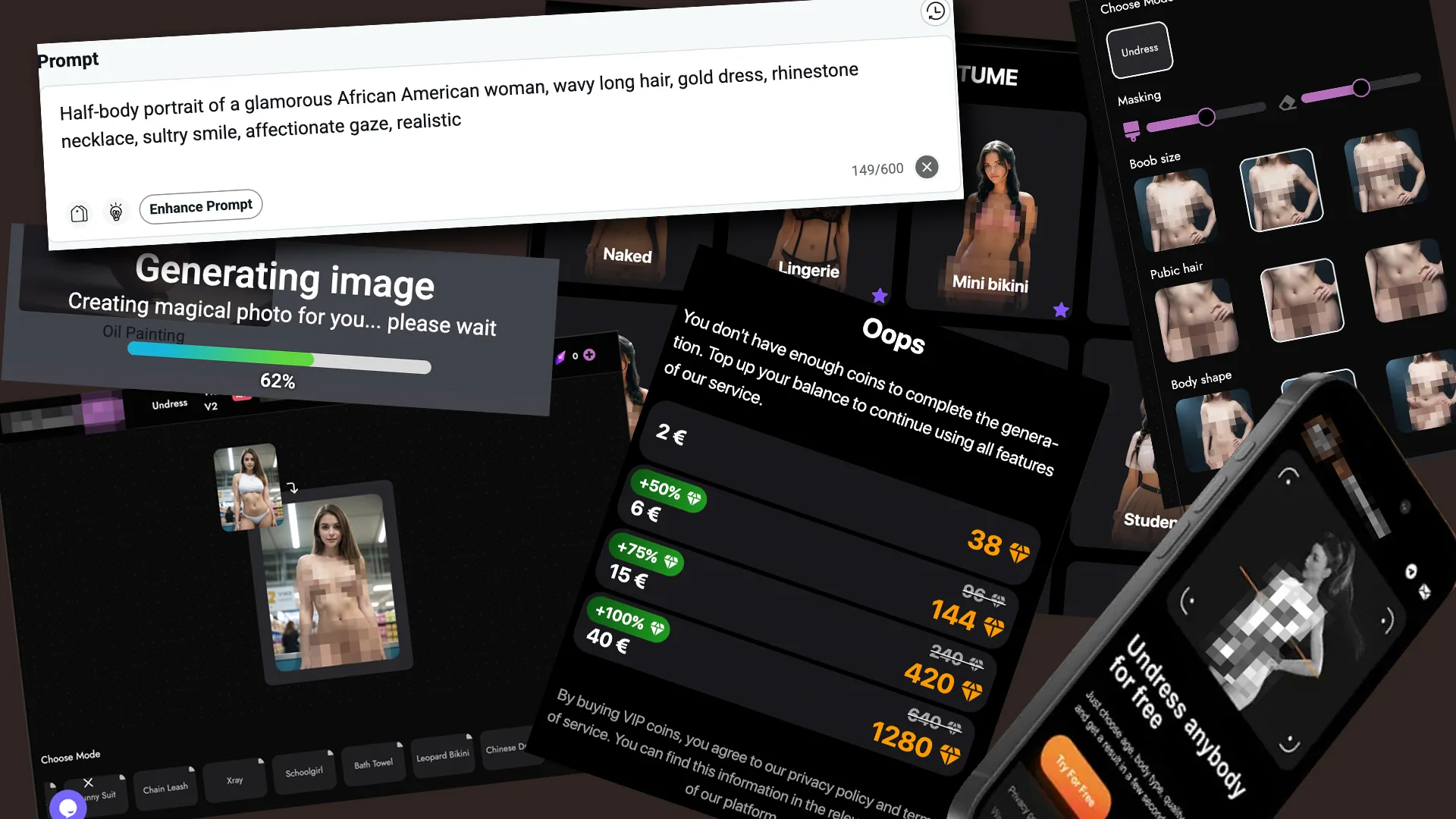

JEP INVESTIGATION: Artificial Realities IT takes less than a minute. You upload a photo – any photo – and within seconds, a new image appears. The same face, the same background, the same expression. Only now, the person is naked. It’s the kind of image that can ruin reputations, relationships, and lives – and it can now be made by anyone with a smartphone. This investigation set out to discover just how easy it is to create one of these fake sexual images – known as deepfakes – and what, if anything, stops someone from doing it to a real person. Of course, testing it with a photograph of a real person comes with serious ethical limitations – so we opted to use an AI-generated portrait of a woman created in ChatGPT. After uploading an image to one platform the JEP has chosen not to name, users can alter breast and “butt” size, select a pose or sex act, and choose an “age range” between 18 and 50. To continue once the free trial has expired, users buy virtual “coins”, which can also unlock longer videos called “premium scenes” such as “student adventures” or “naughty wife”. A support-chat operator named Victor explained that one fake nude photo costs about 36 pence and a video about 82 pence. In other words, anyone could create a pornographic deepfake of another person for less than £1. Many other apps work the same way. Another platform the JEP has trialled but chosen not to name invites users – just seconds after uploading a portrait – to use on-screen sliders to adjust “body shape” and “pubic hair.” A small disclaimer urges users to act “responsibly”, but no checks are made. The site also allows short pornographic videos to be generated from text prompts, giving the example: “lady takes off her clothes, looking at the camera.” It is frighteningly easy to imagine how any real photograph – a LinkedIn headshot, a school photo, a profile picture – could be turned into pornography in seconds, downloaded and shared endlessly online. CGI fakes have been circulating for many years, but when the more sophisticated ‘deepfakes’ started to emerge in 2017, they were confined to small online communities of coders who used complex face-swapping software superimpose celebrities into various situations. Generating a single clip could take hours or even a day, but now the technology has evolved so rapidly that what once required specialist knowledge and expensive hardware can be done instantly by anyone. Jersey has already encountered several issues with ‘deepfakes’ being used by fraudsters – including a fake video circulating online which used artificial intelligence to mimic Chief Minister Lyndon Farnham’s voice and image. The AI-generated clip – which even employed JEP branding to add an air of legitimacy – falsely claimed that Islanders could earn £800 per week by investing £200 in a supposed “government scheme”. In the video, the fabricated voice insisted that the offer is “not a pyramid scheme” and promises to refund anyone who doesn’t profit, but the entire production was a scam designed to trick viewers into handing over money and personal details.But now the States of Jersey Police has confirmed to the JEP that it is also receiving reports of apps being used to create imagery where people’s faces are swapped onto other bodies or made to appear undressed. Such videos can be deeply upsetting for those whose likeness has been used. Bailiwick Express editor Fiona Potigny shared how, during the height of the second wave of covid in November 2020, the online newspaper’s Jersey news team was targeted. “An Islander made a YouTube video, using our byline headshots, and superimposing them onto images of partially undressed people who were being violently tortured while an overlaid narrative accused us of betraying the community through “lies” about masks and the virus,” she recalled. “It was unsophisticated CGI, but even then it was distressing for the team at a time that was already very difficult. With today’s far more realistic AI tools, I can only imagine how much worse it could be. “As part of an investigation last year, we uncovered a series of local Snapchat groups where children shared humiliating – sometimes edited – photographs of each other. It was a form of cyberbullying. One young person told us how, when she was 13, content shared about her had led to a suicide attempt. It is deeply worrying to think how this new ‘deepfake’ technology could be used to harass or bully others, especially young people.” Such technology can also be used for ‘sextortion’ – a type of online blackmail where criminals threaten to share pictures, videos, or information of a sexual nature, unless the victim pays them money. At the end of last month, Guernsey police warned that AI-generated sexual imagery being used as a form of blackmail had become rife. Bailiwick Law Enforcement said there had been a spike in reports among the 14-18 and 18-30 age groups, and that young men and boys are the usual target of such attempts, although anyone could be targeted. “The criminals involved are not technologically sophisticated but know how to emotionally manipulate victims into believing they have no choice but to pay up. This crime plays on the feelings of guilt and shame, which makes it easy to isolate teenagers,” Guernsey’s Digital Safety Development Officer Laura Simpson said. Former Pan-Island Information Commissioner Emma Martins said society still has not “fully grasped” the risks posed by AI. She warned that “everything online is essentially fair game – including images of children and young people that may be innocent holiday or birthday snaps, but in this new world can open the door to something very dark and very dangerous.” She said the lessons of social media had not been learned, warning that AI will only intensify those harms. “Once images have been subsumed into an AI model, the damage is done. On those occasions when a young person tragically takes their life after being blackmailed (sextortion), or we are presented with eye-watering stats about how many children have been victims, and how many images are out there, we get a glimpse into a world which is largely hidden from our view.” “But it is there, and it is growing, and we cannot afford to look away,” she continued. “Parents putting images of their children online need to understand. Schools putting images of pupils online need to understand. We all need to understand.” Ms Martins said that platforms’ business models were built on “attention and time” – leaving little incentive for change. “It is built to be addictive, and it is built to extract the most data it can, because that’s where the huge profits lie,” she said. While regulators can fine companies, she said, “there’s such an enormous asymmetry of power and money that it’s essentially loose change for the platforms.” “I want to be clear that people like me (who care deeply about ethical data handling and governance) do not want to stifle innovation and new technologies. What we want is for an honest conversation to be had about the risks, and to advocate for responsible management by companies and governments. “We are in desperate need of better social and cultural engagement, as well as legal protections. The trajectory is not set, but change will not come from one place. “Tech platforms need to be challenged, governments need to act, lobby groups need to lobby, and citizens need to speak up.” While the creation of indecent images of children – including via AI – is already criminalised, the JEP was told that ministers are already preparing to introduce new laws that would protect more Islanders from becoming victims of sexually explicit deepfakes. The Children, Education and Home Affairs Scrutiny Panel is currently in the final stages of a review into how young people in Jersey are being exposed to online risks. The panel’s chair, Deputy Catherine Curtis, said the report, currently expected to be published next wee,k “covers matters relevant to this”. However, she noted that, whatever changes ministers are planning on making, there will nonetheless be a “huge challenge for legislation and policy to keep up with rapidly advancing technology”. This investigation is one of a three-part Artificial Realities series investigating real-life impacts of AI in Jersey. On Monday, we examine the rise and risks of artificial companionship. The growing deepfake dilemma Monitoring company Sensity estimates that 96% of deepfakes are pornographic, with the majority depicting women without their consent. Analysis by Graphika found that links promoting “undressing” or “nudify” apps increased by 2,400% on social platforms such as X and Reddit in 2023, with 34 providers of fake intimate-image services attracting over 24 million visitors in a single month. More than half the platforms studied in 2024 offered “advanced” features, including the ability to place image subjects in specific sexual positions or generate full videos of sexual acts. The number of deepfakes shared online is expected to reach eight million by the end of 2025, up from half a million in 2023. A 2019 American Psychological Association study found one in 12 women will experience image-based sexual abuse; Australian research the same year put the figure as high as one in three. An analysis of data from 24 police forces in England and Wales from 2019 to 2022 by charity Refuge found that only about 4% of all recorded intimate image abuse offences resulted in the alleged offender being charged or summonsed.