Copyright The New York Times

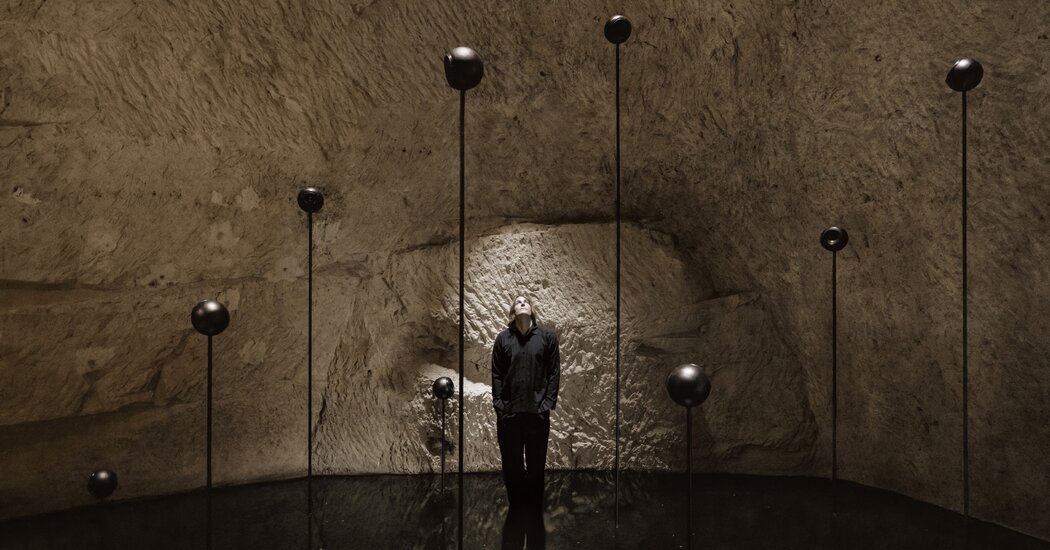

In search of ideas and inspiration, Julian Charrière has climbed an Arctic glacier, scaled Indonesian volcanoes and lowered microphones deep into the Pacific. But recently, Charrière, a 37-year-old French Swiss artist, found a new kind of otherworldly intensity some 35 meters (about 115 feet) underground, inside a wine cellar in Reims, a city about 45 minutes from Paris by train. On the property of the Champagne house Ruinart, around 20 ancient crayères, or chalk quarries — first excavated in the 13th century to extract chalk for building materials — form vast underground chambers. Over time, winemakers realized these excavated areas were perfect for aging and storing wine, thanks to their naturally cool temperatures and stable humidity, and repurposed them as cellars. The chalk walls, formed from the remains of prehistoric marine life, sparked his imagination. He agreed to collaborate only if the project could unfold inside a crayère accessible through Ruinart’s wine cellars. Over the next 18 months, he created “Chorals,” a permanent installation that combines geology and history, drawing on natural light, water and chalk, along with his own recordings of ocean soundscapes. The opening of “Chorals” was scheduled to coincide with the 10th anniversary of UNESCO adding the Champagne hillsides, houses and cellars to its World Heritage list. The installation opened to Ruinart’s guests this summer, and to paying visitors taking the winery’s cellars tour last month. “I was fascinated by the crayères,” Charrière said. “Going down felt like entering the earth, but also a vanished sea. The chalk holds the memory of that ocean in layers of marine organisms built up over millions of years.” “The crayères are man-made yet so old, and dug out so primitively that they feel organic, almost eroded,” he added. “There is a unique energy inside.” At the center of “Chorals” is a pool of black-colored water that reflects the chalk walls. A concealed mechanism ripples the water’s surface. Recordings of ocean sounds echo through the chamber, lit by the blue-gray daylight pouring in from a small oculus some 100 feet above. “My intention was to fill the hollow in the bedrock with the sounds of living reefs, to create a bridge between the material memory of the vanished sea and the fragile marine ecosystems of the present,” Charrière said. “The cave itself becomes an echo chamber that carries these sounds like a chorus.” The recording, which plays on a 10-minute loop, immerses visitors in a three-dimensional soundscape, turning the crayère into a resonant instrument. “I brought those sounds into this place so our ears could hear what is unheard beneath the earth’s surface,” he said, adding that he and his team “studied the cave’s acoustics to find the frequencies at which the chalk would resonate, almost as if it were speaking back.” Visitors can view the installation on guided tours of Ruinart’s underground galleries. Tours are limited to groups of 12, last about two hours and end with a Champagne tasting. Tickets are 85 euros ($98). “Julian brings back to life an ocean that disappeared millions of years ago,” said Fabien Vallérian, Ruinart’s international director of arts and culture. “He connects us to a geological history that still shapes Champagne today.” Vallérian, who joined Ruinart in 2018, works with the company’s chief executive, Frédéric Dufour, to run the house’s art commission program, called Carte Blanche, launched in 2008. Past participants include Eva Jospin and Pascale Marthine Tayou. “Artists are invited to discover Champagne and given carte blanche to shape their own vision,” Vallérian said. “Their works change how visitors experience this place.” A new visitor pavilion designed by the Japanese architect Sou Fujimoto, which opened last October, now serves as the gateway to Ruinart’s centuries-old crayères, garden installations and contemporary art program. Ruinart is the sole Champagne partner of Art Basel, and, during the fair, the company will present photolithographs by Charrière in a dedicated space at the Grand Palais. The works also reflect his interest in the crayères, as they are printed with pigments from ground coral skeletons and layered like sediment. “Julian was the perfect fit for the crayères,” Vallérian said. “Using just water, sound and light, he has produced a powerful work.” Charrière has roots in Champagne: His mother grew up there, and, as a boy, he collected fossilized ammonites near his grandparents’ home. “My grandfather told me there was once a sea here,” he said. “For a six-year-old, that was an impactful moment.” “Julian has been on our radar since he was nominated for the Prix Marcel Duchamp in 2021,” said Xavier Rey, director of the Pompidou Center, referring to the prestigious French art prize that is awarded in partnership with the Pompidou. Rey toured “Chorals” this summer, when it first opened. “He draws on the site’s deep history to question our relationship with nature, blending science and aesthetics as few artists can,” Rey said. “He makes us feel the immensity of the site and measures our lives against a far greater natural scale. Viewers feel a sense awe at that immensity.” The Pompidou acquired a photo by Charrière in 2020, and a year later, when he was nominated for the Prix Marcel Duchamp, the museum presented his installation “Le Poids des Ombres” (“The Weight of Shadows”), which focused on carbon cycles. Charrière’s work has been widely shown, including at the Pompidou, the Venice Biennale, the Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna in Italy, the Palais de Tokyo in Paris and the Dallas Museum of Art. “I first spotted Julian’s work in 2013 in a performance where he used a blowtorch to melt an iceberg in the Arctic Ocean,” said Alice Audouin, an art curator and founder of Art of Change 21, a Paris-based nonprofit organization focused on art and sustainability. “He was accelerating the melting process. I thought, ‘this guy is something.’” A champion of his work, Audouin was instrumental in introducing Charrière to Ruinart. “Julian is an explorer, like Darwin,” Audouin said, adding, “he turns his experiences in extreme places into artworks that make us think about our age-defying ecological challenges in a way that is poetic and thought-provoking.” As Vallérian put it, “Julian usually goes to the edges of the world to rethink our relationship with nature. With ‘Chorals,’ he brings that vision to the vast world beneath our feet.”