Copyright The Boston Globe

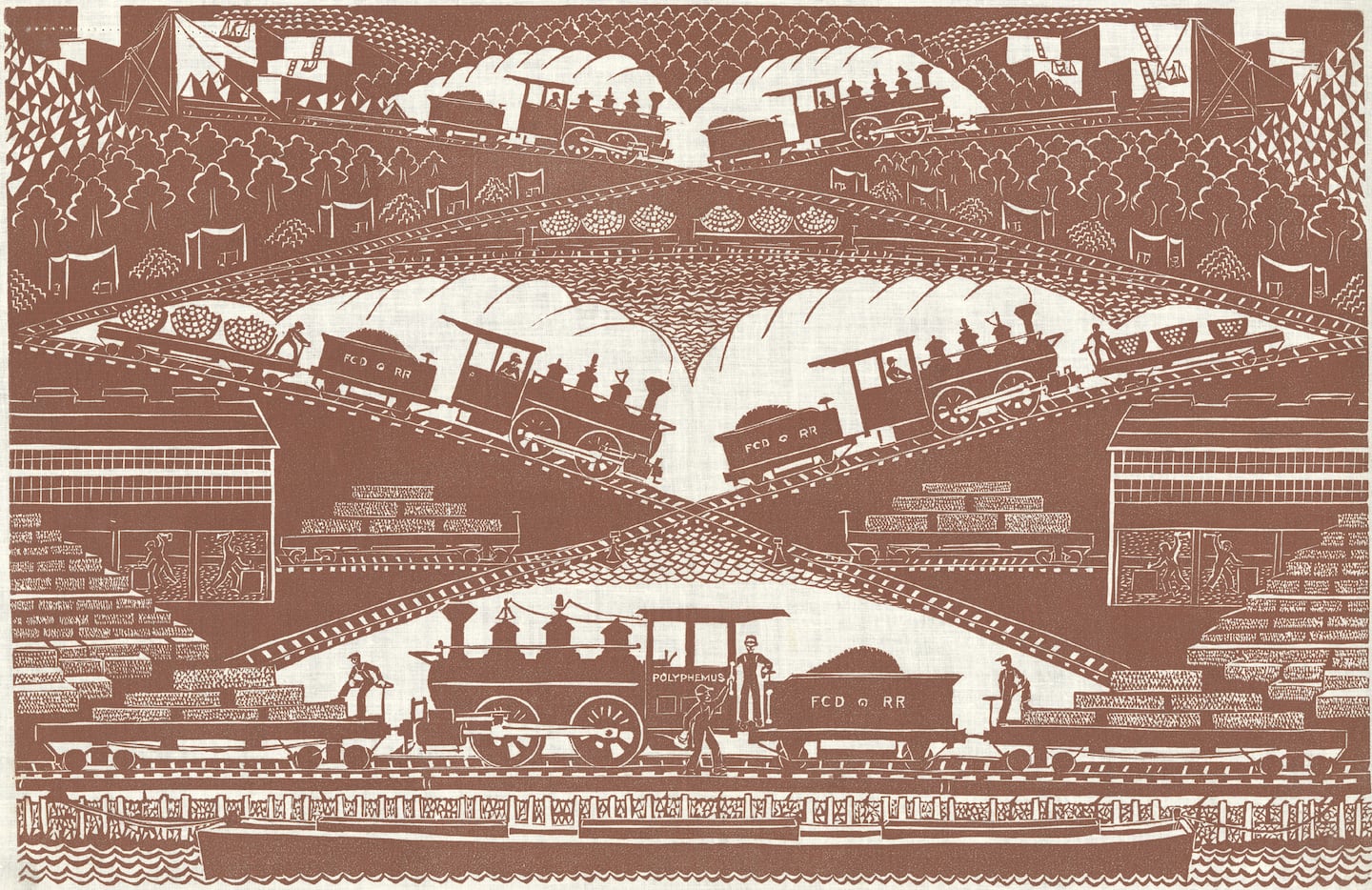

Like those shows, “Hammers” engagingly brings together art and industry. It also touches on economic, regional, and labor history. Indicative of how involved a job quarrying could be, and how extensive a business, is that there wasn’t just a Granite Cutters Union but also a Paving Cutters Union and Quarrymen’s Union. The 18th century saw the start of stone cutting on Cape Ann. It became a commercial industry in the 1820s. By 1892, some 900 men worked at quarrying and related jobs. Up until the 1930s there were more than four dozen working quarries. Not all were large. A site requiring just one or two workers was called a “motion.” There were many uses for the extracted stone. “Hammers” includes a small wooden maquette of a bowl for the two granite fountains outside of Union Station, in Washington, D.C., each made by the Rockport Granite Co. from a 60-ton block of Cape Ann stone. Usually, the granite was put to less exalted uses. The most common was to make paving stones. It wasn’t just the Depression that helped end the industry in the 1930s. It was also the increasing popularity of asphalt. Along with that maquette, more than four dozen other items are on display. Some you’d expect in a museum exhibition: paintings and prints, photographs and sculptures. Others are less conventional: tools, a quilt, a union account book (what fine penmanship the writer had), two pairs of stereopticon cards, and at least one ringer — meaning, a non-Cape Ann item. That would be a cylindrical block of black-speckled reddish granite from Finland. It’s beautiful enough to be a Brancusi. The connection is that many Cape Ann quarry workers were immigrants from Finland or their descendants. There was a high representation of Italians among the quarrymen, too. “Hammers on Stone” never forgets that flesh-and-blood people wielded those hammers to extract that stone. The job of stone breaking was back breaking. “Hammers” takes its title seriously. There are several on display. Other tools include a hand chisel, a pneumatic drill, an oil can, wedges and feathers — no, not the kind that come from birds (both implements were used to split stone) — and two dog hooks, used to pick up large blocks. The name comes from dog holes, which were drilled in the stone to accommodate the hooks. In a nice bit of display, a polished granite block is placed between the pair of hooks. Once quarried, stone had to be transported. The granite-carrying sloop Albert Baldwin, rendered in a ship model by William Niemi, carried up to 200 tons of stone. It had enlarged spars and masts and an onboard mechanical winch, loading boom, and derrick. Rail was another option, as shown in Samuel Lewis Pullman’s 1930 painting “Stone Bridge and Quarry Tracks.” Eino Natti’s charming linoleum-block print shows the locomotive Polyphemus, used for pulling stone-carrying hopper cars. The workers who loaded and unloaded the cars were known as “lumpers.” The pleasures “Hammers” has to offer are verbal as well as visual. If the print looks a bit like one of Virginia Lee Burton’s illustrations for “Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel” or “Katy and the Big Snow” that may be because Burton founded Gloucester’s Folly Cove Designers and Natti was a member. Oh, and that oil can mentioned above? It was used on the Polyphemus. Putting that block of granite between those dog hooks isn’t the only canny bit of curation in “Hammers.” Quarries are strange, even paradoxical, things. They are landscape seriously, even gruesomely violated. Yet that violation can unveil great beauty, both in the stone and with the sites themselves. That beauty is very much evident in Steve Rosenthal’s photograph “Quarry Structure 1″ (Rosenthal has spent many years documenting the Cape Ann quarries) and David B. Crowley’s painting “Cathexis.” Or there are the paintings that make up Michael McKinnell’s “Quarry Triptych.” They look like abstractions, yet in what they depict they are as real and solid as subject matter can be. McKinnell was an architect, best known for helping design Boston City Hall. “In architecture, I’ve always been interested in materials,” he once said, “showing how the stuff is formed.” “How the stuff is formed” could be an alternate title for “Hammers on Stone.” HAMMERS ON STONE: The Granite Industry on Cape Ann At Cape Ann Museum, CAM Green Campus, 13 Poplar St., Gloucester, through Feb. 1. 978-283-0455 x110, www.capeannmuseum.org