Copyright The Atlantic

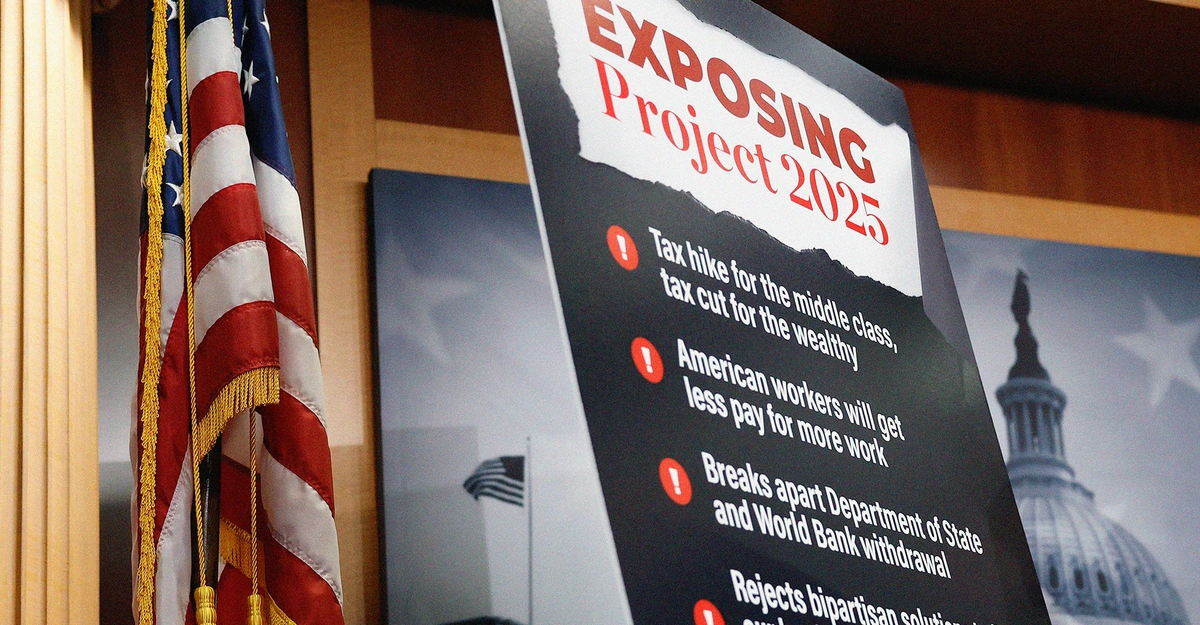

This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here. Did you hear about the new Democratic Party postmortem on the 2024 election? Perhaps I need to be more specific: There’s this one, that one, and also this one, and probably more that I’m missing. Postmortems are a recurring motif among Democrats, who have long “interpreted every loss as an utter rejection of their party and a signal that they needed to make major changes in the way their party was run, what it stood for, and how it picked candidates,” as the political scientist Seth Masket writes. But Donald Trump’s reelection has prompted an especially frantic round of soul searching. Rather than producing a clear consensus, the diagnoses and prescriptions that emerge from these reports tend to bear uncanny similarity to the preexisting political views of the specific authors and the organizations commissioning them. One point of convergence since Trump’s win, though, is how often the reports, and news coverage of them, have invoked Project 2025, the right-wing plan that has become a blueprint for the Trump administration, as a sort of model. One effort to reshape the party has even christened itself “Project 2029.” This got my attention because I wrote a book about Project 2025. Democrats didn’t seem to understand the project during the election; their elected officials weren’t ready for Trump’s second-term blitz, even though they had two years to prepare; and now the people citing it as a political model misunderstand the authors’ goals on a basic level. Project 2025 starts with a deeply held ideology, and approaches policies and politics only as a means of turning that ideology into practice. By contrast, the progressive postmortems show less interest in laying out a worldview. Instead, they mostly start from the position that the Democratic Party’s central problem is tactical and electoral. Their recommendations all circle the question of how to win: Does the party need better policy solutions? Does it need to govern better when in power? Has the party allowed itself to become captured by unpopular left-wing ideas? The approach is understandable. The Democrats are deeply unpopular, including with their own voters, and the past few elections have shown an erosion of the party’s vote share with groups including young men, Black men, and Hispanic people. (The political scientist Jonathan Bernstein offers a contrarian argument that Democrats’ electoral prospects aren’t actually that dire, noting that their candidates outperformed expectations in 2024 and that Trump is very unpopular.) One new report this week, from the centrist Democratic organization Welcome, declares its electoral orientation right in the title: “Deciding to Win.” The report’s contention is that “since 2012, highly educated staffers, donors, advocacy groups, pundits, and elected officials have reshaped the Democratic Party’s agenda, decreasing our party’s focus on the economic issues that are the top concerns of the American people. These same forces have pushed our party to adopt unpopular positions on a number of issues that are important to voters, including immigration and public safety.” The group that calls itself Project 2029 focuses less on how liberal or moderate certain policies are and more on their inherent merits. Its founder, Andrei Cherny, told The New York Times that the project will gather “the best thinkers from across the spectrum” of the party, which is so disparate that it runs from the moderate Representative Marie Gluesenkamp Perez to Zohran Mamdani. In other words, Project 2029 is not just nonideological—it’s anti-ideological. These may be worthwhile efforts, but they bear little resemblance to Project 2025, which is not an electoral project. Project 2025 begins with an ideology—a desire to build a very traditional, male-dominated, Christian-nationalist society—and only then starts outlining which policies might bring it about. This vision is not popular, and polling last year by the Heritage Foundation, which convened Project 2025, found strong disapproval among voters in battleground states. But the authors believe deeply in their worldview, and to them, that supersedes popularity with voters. The authors of “Deciding to Win,” along with other Democratic figures, argue that the party’s broader, philosophical warnings about Trump’s danger to democracy in 2024 were a political error. These critics insist that Democrats must focus on a more practical economic message to win. But Project 2025 elevates ideology above practicality: It argues forcefully that liberal government is a threat to the Constitution, and offers only a skeletal economic program, which is neither popular nor populist—ending the Fed, cutting taxes on the wealthy, deregulating the financial sector. And it barely addresses inflation, a top issue for voters in 2024, at all. Project 2025 may not be the best model to emulate anyway. What works for a demographically and politically homogeneous Republican Party may not work as well for the more fractious Democratic Party. Project 2025’s success as an election strategy is also somewhat accidental, because Trump tried to disown it during his campaign. But thinking about the contrasting approaches of Project 2025 and these left-of-center efforts reminded me of the “autopsy” conducted by the GOP following Mitt Romney’s defeat in the 2012 presidential election. The party concluded that in order to win, it would need to be more inclusive and open, adopting minority outreach more like the Democrats. And crucially, it needed to change its tone on immigration, including embracing “comprehensive immigration reform.” The party’s next nominee, much to the horror of its establishment, was Trump, who rejected the autopsy’s prominent argument to embrace immigration—yet won with a campaign focused on reducing immigration, while also increasing his share of the vote among minorities. That’s the rub with these postmortems: There’s usually not one single way to win, and if it were obvious, everyone would do it. Related: Here are three new stories from The Atlantic: Today’s News Dispatches Explore all of our newsletters here. Evening Read The Movies That Capture Women’s Deepest Fears By Sophie Gilbert Read the full article. More From The Atlantic Culture Break Explore. Thomas McGuane—fisherman, hunter, rancher, writer—is the last of his kind, Tyler Austin Harper writes. What will we lose when we lose the “literary outdoorsman”? Watch. Love Is Blind’s latest season (out now on Netflix) had a notably old-fashioned streak that ended in a breakdown of the show’s premise, Julie Beck writes. Play our daily crossword. Rafaela Jinich contributed to this newsletter.