Israel’s illegal September 9 attack targeting Hamas senior leadership in Qatar is reportedly setting off alarm bells in Türkiye, which allows Hamas to maintain a presence in the country.

Turkish officials are understandably expressing concern that if Israel can try to bomb Hamas negotiators with US blessing in a US-allied country, what’s to prevent Israel from striking Ankara or Istanbul? Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu made the threat clear when on September 10 he declared the following:

“I say to Qatar and all countries that provide sanctuary to terrorists – either deport them or bring them to justice. If you don’t do this, we will.”

And following the Doha attack, Channel 12 in Israel reported that Israel is considering similar military strikes against Türkiye. Does this mark another step in the long-awaited conflict between “Greater Israel” and “Greater Türkiye,” or is it more sound and fury signifying little? Let’s look at both sides of that argument, starting first with a brief history of the war of words between the two sides over the past two years.

Fake Action and Heated Rhetoric

Despite criticizing Israel’s actions for the past two years, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan continues to face mounting political pressure at home to actually back up his words with concrete action.

The government made another attempt to placate the public with an August decision to formally close Turkish ports and airspace to Israeli vessels and aircraft. But foreign-flagged ships still sail from Turkish ports to Israel, as the Cradle notes:

Tankers frequently disable their tracking systems in the eastern Mediterranean, feign destinations in Egypt or elsewhere, and arrange deliveries through third-country traders.

Russian Telegram channel Dva Mayora exposed Greek tankers Seavigour and Kimolos for involvement in these covert routes in 2025. As of 22 August, the Marshall Islands-flagged Nissos Antimilos was seen 190 kilometers west of Haifa, fresh from Ceyhan and awaiting an Israeli tanker for offshore transfer.

This is just the latest workaround Ankara has come up with to try to mask its support of Israel. In May of 2024, Türkiye halted all direct trade with Israel, but simply re-routed it through Palestinian territories.

This means that nearly two years into a genocide that Erdogan denounces almost daily, oil still flows from Azerbaijan to Israel via Turkiye, Israel still gets critical minerals from Türkiye, and the Incirlik air base in Turkiye is still used by the US to deliver weapons to Israel and monitor the region’s skies to defend Israel and aid its agression.

A group of 76 Turkish academics, writers, politicians and rights activists recently signed a statement criticizing the lack of action from the government in Ankara. In particular, they panned a resolution recently passed in the Turkish parliament that condemns Israel, calling it a “cosmetic” move in the place of sanctions.

Meanwhile, Erdogan has the chutzpah to call on Arab and Muslim nations to sanction Israel (it’s unclear if Türkiye would join them), and continues to crack down on dissent at home, which is part of an effort to silence criticism of his lack of action against Israel.

And the Turkish public is treated to an argument over genocide—past and present. Erdogan accuses Israel of a genocide that overshadows the Holocaust, which again begs the question as to why he’s not doing more to stop it. Netanyahu, in turn, recognizes the Ottoman genocide of Armenians during World War I. It’s all nice theater, but matters little to the Palestinians facing extermination in Gaza. And where it really counts, Türkiye continues to fuel that intensifying Holocaust.

Putting Türkiye in its Place

Despite Ankara’s support for Israel’s genocide, areas of friction remain. Cyprus has emerged as one flashpoint. Earlier this year when Israel President Isaac Herzog visited Cyprus and met with his counterpart Nikos Christodoulides, the latter said the following:

We need to discuss regional developments, the situation in Syria and Lebanon. There is one neighbour that always is trying to create problems in our neighbourhood. We’ll exchange notes.

And he wasn’t talking about Israel. This comes on the heels of the US lifting its 33-year arms embargo on Cyprus in 2020 and Israel moves to become a regional energy hub. It is eyeing control over reserves in the Eastern Mediterranean offshore of Lebanon, Gaza, Syria, and Egypt, and has discussed plans with Cyprus and Greece to supply Europe via pipeline. This puts Israel at odds with Türkiye, which has its own plans to become a regional energy hub.

In Syria, the US-Israel is trying to put the squeeze on Türkiye by constantly working to thwart Türkiye’s goal of a stable proxy extremist regime under Al Qaeda-turned-statesman Syrian President Ahmed al-Sharaa. In April, Azerbaijan helped mediate some sort of deconfliction mechanism between Israel and Türkiye in Syria, but how well does that usually work between two sides that aren’t agreement-capable? It was just weeks ago that Israel struck and destroyed Turkish surveillance equipment in Syria, although it didn’t yet lead to war so maybe there’s something to that April mechanism after all. It’s hard to see how it will continue to function, though, with Israel’s goals in direct opposition to Türkiye’s. As The Cradle notes:

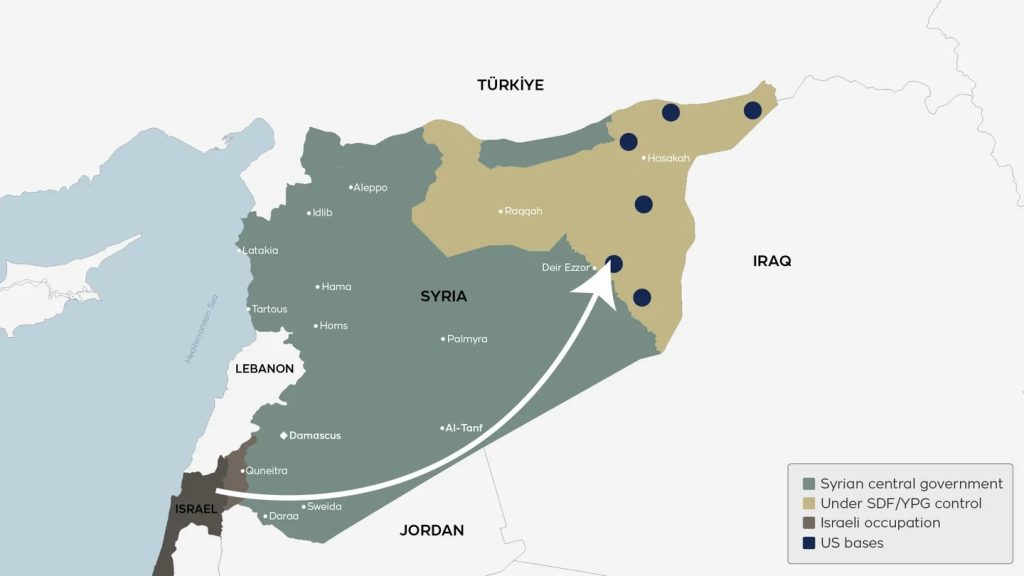

“Israel seeks to exploit Syria’s sectarian and ethnic divisions to use minorities as political and military tools, serving its plan to partition the country and open two strategic corridors: an eastern one linking Suwayda to Hasakah, and a western one running from Syria’s coast to Afrin, securing multi-front influence and encircling the Turkish axis from within.”

Israel calls the Eastern one “David’s Corridor”:

And so Türkiye arms and trains an army of takfiris (also known as the Syrian army), and Israel uses that army and their repression of minorities as an excuse for why it must bomb the country and establish a route to Kurdish territory in northwestern Syria that links up with Iraq’s autonomous northern Kurdish Regional Government , which also happens to border Iran.

At the same time, Türkiye’s peace process with the Kurds looks on the surface like it’s no longer working to Erdogan’s advantage:

In Syria, where Turkiye helped dismantle the state, the US-Israeli axis has imposed limits on Ankara’s ability to resolve the status of the Kurdish-led SDF.

Negotiations between the SDF and the Damascus-based transitional government, including a landmark 10 March agreement integrating SDF-controlled civil and military institutions into state structures, reveal a growing potential for a Kurdish political presence to be formalized within Syria’s new political order.

In July, US envoy and Ambassador to Turkiye Tom Barrack made clear that the SDF remains an offshoot of the PKK, stating, “SDF is YPG. YPG is a derivative of the PKK. … There’s no indication there’s going to be a free Kurdistan, … There’s Syria.”

Back in February, French President Emmanuel Macron implored the Al-Qaeda-rooted Syrian interim government to “fully integrate” the SDF into Syria’s political transition, calling them “precious allies.”

As Kurdish influence shrinks in Anatolia, it expands across the Levant, underwritten by the US, Israel, and France. The developments shaping Turkish–Kurdish relations are now being dictated by forces beyond Turkiye’s borders.

Just to play devil’s advocate for a moment, a few points:

If Erdogan, through his peace efforts with the PKK, gets another term in office then he comes out a winner. He is now saying that to achieve peace the Turkish constitution must be rewritten in order to enact education rights and administrative reforms. The constitution also happens to need tweaking in order for Erdogan to stand for another term. And he needs the votes of a pro-Kurdish party in order to make these changes.

If Kurdish influence moves from Anatolia to the Levant and Iraq, that could also be considered a win for Erdogan. Türkiye could likely live with an agreement that sees Kurdish-controlled areas remain part of Syria and save the fight for another day.

And if the US and Israel can use strengthened Kurdish forces to help destabilize Iran, as think tanks and ex-officials publicly drool over, well, that would work just fine for Ankara, Washington, and Tel Aviv. Türkiye would like nothing more than to have Kurds fighting and dying to weaken Iran.

***

The relationship between the West and Türkiye has long been of the transactional stop and go variety with both sides looking to use one another against common targets: Türkiye looked to the US to help balance Russia and Iran and Washington wanted to use Türkiye to further its goals of Moscow and Tehran.

And so the US oftentimes tries to keep the pressure on Türkiye in one arena while seeking its cooperation in another.

Is the tension with Israel a continuation of this dynamic or does it represent something new? The answer to that question might depend on whether one views Israel as largely a US proxy with Washington pulling most of the strings or its own out of control eschatological force that is doing the puppeting these days. Those lines appear increasingly blurred at the moment, but either way it’s hard to see how a conflict with Türkiye would be in either the US or Israel’s interest.

Forty percent of Israel’s oil needs flow through Türkiye, and Ankara is also key to US (and Israeli) goals in other areas.

Let’s not forget Türkiye is a key player and benefiter in the Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity (TRIPP), also known as Project Iran Encirclement: Caucasus Edition. Washington and Israel would like to direct those Greater Türkiye ambitions eastwards where a Pan-Turkic Corridor can double as a NATO one slicing into Central Asia. Both TRIPP and the David’s Corridor can be read as part of preparations for more conflict with Iran:

Elsewhere, as we’ve frequently pointed out, Türkiye’s defense industry is being increasingly relied upon as the West scrambles to keep up with supplying all its conflicts. Here’s Türkiye’s Anadolu Agency touting that growing relationship last month:

The ripple effects of the Ukraine war and a shifting transatlantic relationship have led European states to urgently reassess their defense postures.As nations scramble to strengthen capabilities and diversify suppliers, Türkiye has emerged as a key alternative with battle-tested systems and reliable, timely delivery.

Türkiye’s defense exports to Europe surged to $1.2 billion in 2023, up from $369 million in 2020. They now account for 22% of the country’s total defense exports.

The NATO Leaders Summit in The Hague in late June gave further momentum to this trend. Pushed by US President Donald Trump, allied countries pledged to increase defense spending to 5% of GDP by 2035 – more than double the previous limit.

“Türkiye has a very big defense industrial base. Sometimes (we) forget what they have. I visited some of their companies – it’s really impressive,” NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte said during the summit.

In late May, the EU also activated its new €150 billion ($171 billion) defense fund – the bloc’s first large-scale defense investment program.EU foreign policy chief Kaja Kallas later told reporters that, as an EU candidate country, Türkiye could participate in joint projects. “We definitely see Türkiye as a security player,”

For obvious reasons Ankara is eager to gain access to the EU’s new $170 billion defense fund. The country’s defense industry could get another big boost if the US eases up on 2017 the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) restrictions on Türkiye. That’s increasingly looking like a question of when.

Washington imposed sanctions on Ankara in 2020 over its purchase of the Russian-made S-400 missile defense system. Erdogan said a few months ago that the sanctions, which have hammered Türkiye’s defense sector, are softening and that steps toward lifting them are progressing rapidly. It now looks like Türkiye might be getting close to unloading the S-400s, which have never even left the box.

What does this all add up to? Well, it sure looks like there is a lot more agenda overlap between Ankara and Washington than not. Israel has little to gain in direct confrontation with Türkiye, and a lot more to lose. Türkiye also has the ability to complicate US strategy, which gives it some leverage in the contest of “Greaters” in the region.

Is this one area where the US actually has to rein in Israel—if it indeed still can—as Türkiye is so important to US (and Israeli) designs in other areas? It’s impossible to put anything past any of these actors as none are agreement-capable, and it wouldn’t be surprising to find one stabbed in the back tomorrow.

It also wouldn’t be a shock if a lot of this friction between Israel and Türkiye was more of the deceptive theater Israel and the US are so fond of these days, and behind the curtains they remain unified on the goal of toppling the government in Tehran.