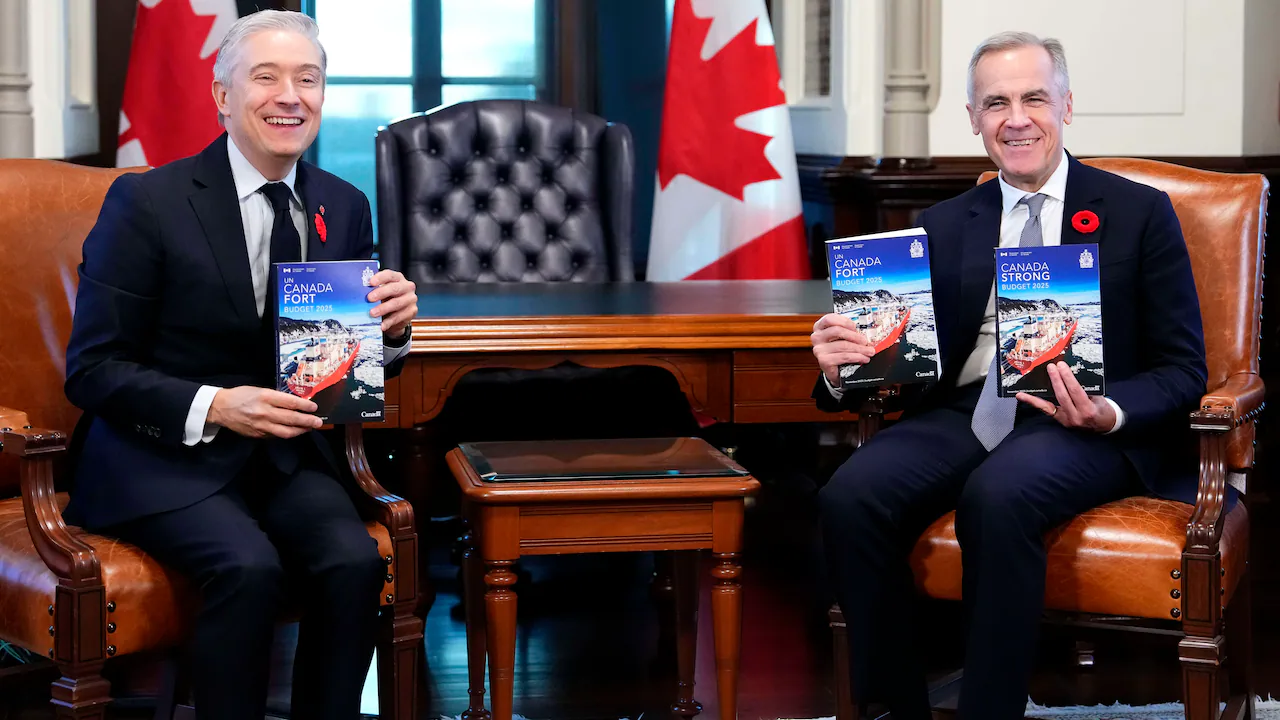

Copyright cbc

"Generational" is the Carney government's adjective of choice at this moment of consequence. The word appeared 11 times in the prepared text of François Philippe-Champagne's budget speech and another 45 times in the 493-page budget document. It is a word apparently meant to speak to both the gravity of the country's situation and the bigness of this government response. "This is not a time for small plans," Champagne writes in the budget's foreword. The word also assumes some kind of lasting significance — both for this moment and for the government's response. As much as one should be humble about predicting the future relevance of the present, it seems safe to assume that this moment will matter, even if we cannot know exactly how. But the exact significance of this budget might depend on what happens over the next 12 months. The budget's big numbers The first big number to be focused on will inevitably be the deficit — $78.3 billion in the current fiscal year, falling gradually to $56.6 billion four years from now. That deficit for 2025-26 is $36 billion higher than what Justin Trudeau's government projected last December — on the day Chrystia Freeland effectively brought the Trudeau era to an end — and $16 billion higher than what Mark Carney's Liberals projected during this spring's federal election. But it's also still relatively modest when compared with previous moments of national crisis. As a share of GDP — the deficit in relation to the size of the national economy — it's projected to peak at 2.5 per cent. At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the deficit was 14.8 per cent of GDP. During the Great Recession, Stephen Harper's Conservative government ran a deficit equal to 3.6 per cent of GDP. (During the Second World War, the deficit reached 22.5 per cent of GDP.) Given that some projections suggested the deficit could reach $90 billion, the actual deficit might seem less dramatic. But, as always, the size of a deficit matters less than how it is used. The single biggest item line over the five-year plan is an $56.6-billion investment in the Canadian Armed Forces. The second-biggest expense is actually the income-tax cut that the government passed in June ($27.2 billion). A little over $20 billion is put toward a "generational" investment in infrastructure. $1.5 billion will go toward tax measures meant to boost business investment. $12 billion is set aside for protecting and reorienting strategic industrial sectors and $4.4 billion will be put toward expanding trade. $7 billion is committed toward a new Crown agency — Build Canada Homes — that will focus on affordable housing. Aside these expenditures is a significant set of cuts — the budget touts $60 billion in "savings" over five years. Some of these cuts are at least broadly acknowledged — "recalibrated international assistance" will save $2.7 billion over four years. But much of the reductions in departmental budgets are shrouded in euphemisms like "modernizing government operations," "streamlining program delivery" and "recalibrating government programs." Perhaps some of that modernizing, streamlining and recalibrating will be relatively easy. But no doubt some of it will draw loud complaints in the months ahead as the actual implications become clear (interestingly, the word "sacrifice" appears in neither the budget nor Champagne's speech). Change or more of the same? The budget itself is a sweeping document, comprising both a new immigration plan and the outlines of a new climate strategy. Sprinkled throughout are hints that this is not Justin Trudeau's government anymore. Annual permanent immigration will decline slightly and temporary admissions will drop sharply. The size of the federal public service will shrink by 10 per cent. The cap on greenhouse gas emissions from the oil and gas sector will be abandoned — at least so long as provinces are willing to agree to a long-term plan for pricing industrial emissions. The plan to plant two-billion trees — a number Trudeau himself picked — has been chopped in half. A luxury tax on private jets and boats is being scrapped (Champagne told reporters on Tuesday that it cost more to collect the tax than it raised in revenue). The most generational change, at least for federal fiscal policy, might actually be an accounting change — Carney's choice to balance the government's "operational" spending while ensuring that deficits will only be used to finance spending on capital within three years. If that rule is followed, it has the potential to fundamentally reorient federal spending, says Sahir Khan, executive vice-president of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy — effectively capping how much the federal government has to spend on the sorts of social programs and transfers that defined the Trudeau era. "If you're a province and you're asking the federal government for money for health care, that transfer would come out of the operating budget, which they now have to balance. So they can't borrow for it," Khan says. "They can borrow for capital. So you're probably going to have better luck if you bring [a request for] a hospital or a long-term care facility." For Conservatives, this was all still too much of the same. "It's the same ministers making the same policies, making the same promises, 10 years later," Conservative deputy leader Melissa Lantsman told CBC's Power & Politics on Tuesday. "They promised you investment 10 years ago." Will MPs — and Canadians — support the Carney agenda? It is true that the Trudeau Liberals also came to office promising to stimulate economic growth with higher government spending. And so some of this budget's legacy will depend on the Carney government's ability to move both faster and smarter — to not only create generational change, but to also show results in relatively short order. But for this budget to have a generational impact, the Carney government also likely has to remain in office for a while — either by winning support in the House of Commons or by winning the votes of the public in another election. While the title of the budget is "Canada Strong" — the theme of the Liberal campaign this spring — Carney's Liberals are still short of a majority in the House. (Granted, if a couple more Conservatives join Chris d'Entremont in crossing the floor, the Liberals might get their majority.) The prime minister had talked about tough choices to come. Nine months into his premiership, he has made a raft of choices that he will now have to defend — choices that include both spending more in some areas and less in others. He will be challenged from both ends. The truth of this moment is that responding to it was always going to require more than one budget. It still remains to be seen how many of those budgets a Carney government will get to table.