Copyright newstatesman

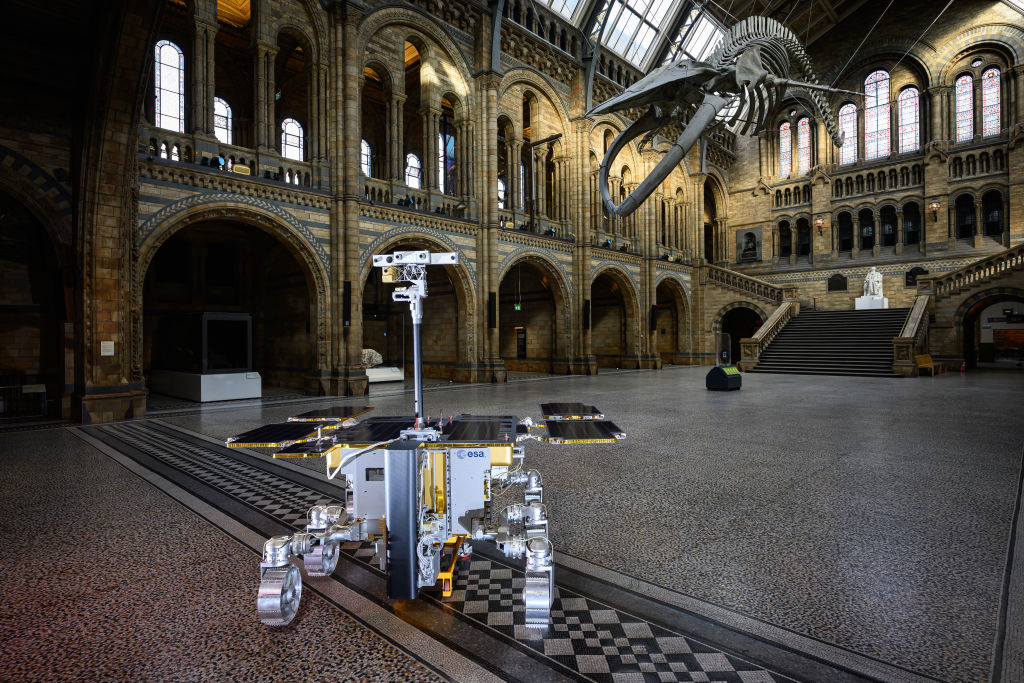

A thatched spaceship drifts towards the stars. A Union Jack-emblazoned high-speed train powers through a rainforest. A rocket takes off in front of Big Ben. This isn’t science fiction, this is Anglofuturism. Bubbling up from the collective consciousness of the online right, for years it existed mostly as AI-generated images. While the settings are diverse, they share a common thread: imagining a homogenous and high-tech Britain, one that combines the demographics and cultural dominance of the 1850s with the technology of the 2050s. In a 2022 essay in UnHerd the writer Aris Roussinos proposed “Anglofuturism” as a solution to national stagnation, arguing that Britain needs a bold programme of national renewal, but one that is rooted in “the best of the past”. Recently the idea has gained momentum. In June at the “Now and England” conference, Robert Jenrick, the likely next Tory leader, told an audience: “I am what can be described as an Anglofuturist”. There’s no Anglofuturist manifesto, but supporters envision a world where technology and tradition coexist. In the idea’s broader implications, it’s also a world in which a distinctly white British cultural identity is preserved. Anglofuturism owes much to Afrofuturism, an aesthetic movement that depicts other realities and futures as a way for black people to imagine an alternative system, one that centres their agency and freedom. Whereas Afrofuturism seeks to give a historically oppressed minority a way of imagining a better world, Anglofuturism is the opposite. It is fundamentally a philosophy of self-pity. The Anglofuturist dreams of returning to the Victorian era, when Britain bestrode the world as a colossus, the sun never setting on its empire, etc. That such dominance came at the expense of its colonial subjects is glossed over. They demand that “the future is made in Britain”, at the same time arguing that the nation’s heritage must be perfectly preserved. In that sense Anglofuturism contains the very paradox paralysing Britain: how can a country whose identity is so grounded in past glories achieve new ones? Or, to put it plainly, how can a multicultural society connect to a past where it wasn’t one? There’s a strange melancholy running through all of it, something close to what Orhan Pamuk calls hüzün in his book Istanbul: Memories and the City. Pamuk describes hüzün as a shared, collective sadness, a kind of civic grief that lingers after an empire’s fall. The feeling is not individual but ambient – a pride turned inward, a grandeur curdled into gloom. Anglofuturism is a British hüzün: the ache of a former empire that cannot quite admit it has fallen, the comfort of decline disguised as destiny. It turns nostalgia into an aesthetic and paralysis into a mood-board. Anglofuturists are acutely worried that Britain has become “museum island” or “butler to the world”. But their reaction to that anxiety is not reflection but reconstruction. In the language of the cultural theorist Svetlana Boym this is “restorative nostalgia”: the belief that the lost home can be rebuilt, that the past can be restored to working order if only the right aesthetic is applied. Reflective nostalgia, by contrast, lingers in the loss and recognises its impossibility. Anglofuturism can’t do that. It refuses to mourn so it mythologises. It mistakes self-pity for pride and aesthetic for vision. For some adherents, Anglofuturism is a primarily white Anglo future, a fantasy of cultural and racial dominance masquerading as technocratic renewal. Anglofuturism is typical of the new online right, skilfully blending so-called hot takes with heavy irony. It’s also a broad church, with both nasty adherents (anonymous X accounts calling for mass deportations) and harmless, nerdy ones (a recent episode of the Anglofuturism podcast made the case for Pingu as a representation of English settler colonialism). The mistake made by a recent article on Hope Not Hate’s website was to lump them all together. If one person who shares the same views as you is racist, the thinking goes, then you must denounce those views. If racists like brutalist buildings, then all brutalist buildings must be torn down. It’s a tired tactic that elicits the mental image of a quivering man hiding behind the couch while Pingu plays on the television. Anglofuturism dares you to take it seriously, then arches an eyebrow when you do. It’s not the first time Britain has been lost in the past . The Victorians themselves were obsessed with ruins, with gothic revivalism and the romance of decay. They built neo-medieval cathedrals in the middle of the industrial age and dreamed of a mythical Albion. Even William Blake’s “Jerusalem” – “and was Jerusalem builded here” (answer: no it wasn’t) – is the same impulse in poetic form: a longing for a past that never was, dressed as a desire to build a kingdom of heaven on Earth. Anglofuturism is their descendant, except the ruins are now digital, rendered by AI and shared on Discord. The yearning has simply found a new medium. In Time Shelter, the novelist Georgi Gospodinov describes a clinic where dementia patients live inside rooms recreating different decades of the past. Eventually healthy people begin to check in. Entire countries hold referendums to decide which decade they will live in. Anglofuturism is one such time shelter. Its proponents claim to imagine the future, but in truth Britain is so infected with nostalgia that even its young can’t imagine a future that isn’t just a simulacrum of the past. The philosopher Jean Baudrillard described the simulacrum as a copy without an original. Anglofuturism is precisely that: a future built from reproductions of fantasies that never existed. Its gleaming rockets and thatched spaceships are not symbols of progress but symptoms of confusion. We live in an age of constant change – technological, ecological, social – yet Britain’s imagination moves in circles. It replaces possibility with replication, innovation with irony. Pamuk’s hüzün at least carries dignity, a kind of mournful self-awareness. Britain’s version turns inward and defensive, as if the only way to protect identity is to freeze it. Anglofuturism’s tragedy is that it mistakes memory for destiny. It longs for a world that has already disappeared, one that perhaps never truly existed. Its rockets never leave the launchpad; its high-speed trains circle endlessly through the same landscape of heritage and decline. It is not science fiction but the theatre of arrested development. When Jenrick called himself an Anglofuturist this summer, the remark may have been wry, but it reveals how the movement has seeped into the corridors of power. Yet his own party’s policy apparatus consistently fails at infrastructure delivery. The Conservative Party has become the party of the gerontocracy. As one analysis puts it, the Tory leadership and parliamentary majority reflect a society where older voters dominate, where planning is frozen, where new homes are blocked and investment is delayed. A party beholden to pensioners, landowners and Nimby-activists has little interest in building the future. Thus the nostalgia of Anglofuturism appeals: it promises a Britain that “once did great things” and might again. For a gerontocratic party inert in its actual delivery of high-speed rail lines, clean power stations and new towns, the fantasy of a high-tech Victorian empire plays to comfortable prejudices rather than to disruptive transformation. The contrast between the rhetoric of a “future made in Britain” and the record of delayed infrastructure is stark. Nostalgia promises comfort but thrives on absence. The more we try to rebuild what’s gone, the more its loss defines us. Anglofuturism is what happens when nostalgia stops being reflective and becomes restorative – when memory turns into mission. It rebuilds the ruins rather than mourning them, believing that if the old symbols can be made shiny again the old certainties will return with them. Pamuk’s hüzün allows sorrow to be shared; Anglofuturism denies sorrow altogether. Baudrillard might have said it produces copies of a future that never existed. It’s not hope that drives it but the refusal to grieve. The Victorians once looked back on medieval England with yearning, and Blake imagined Jerusalem among dark satanic mills. Anglofuturism stands in that same lineage of longing. In the end its retro rockets and thatched spaceships point not to the future but to a nation circling its own ruins, unsure whether to rebuild them or finally let them go. [Further reading: The prophet of the new right]