Copyright Star Tribune

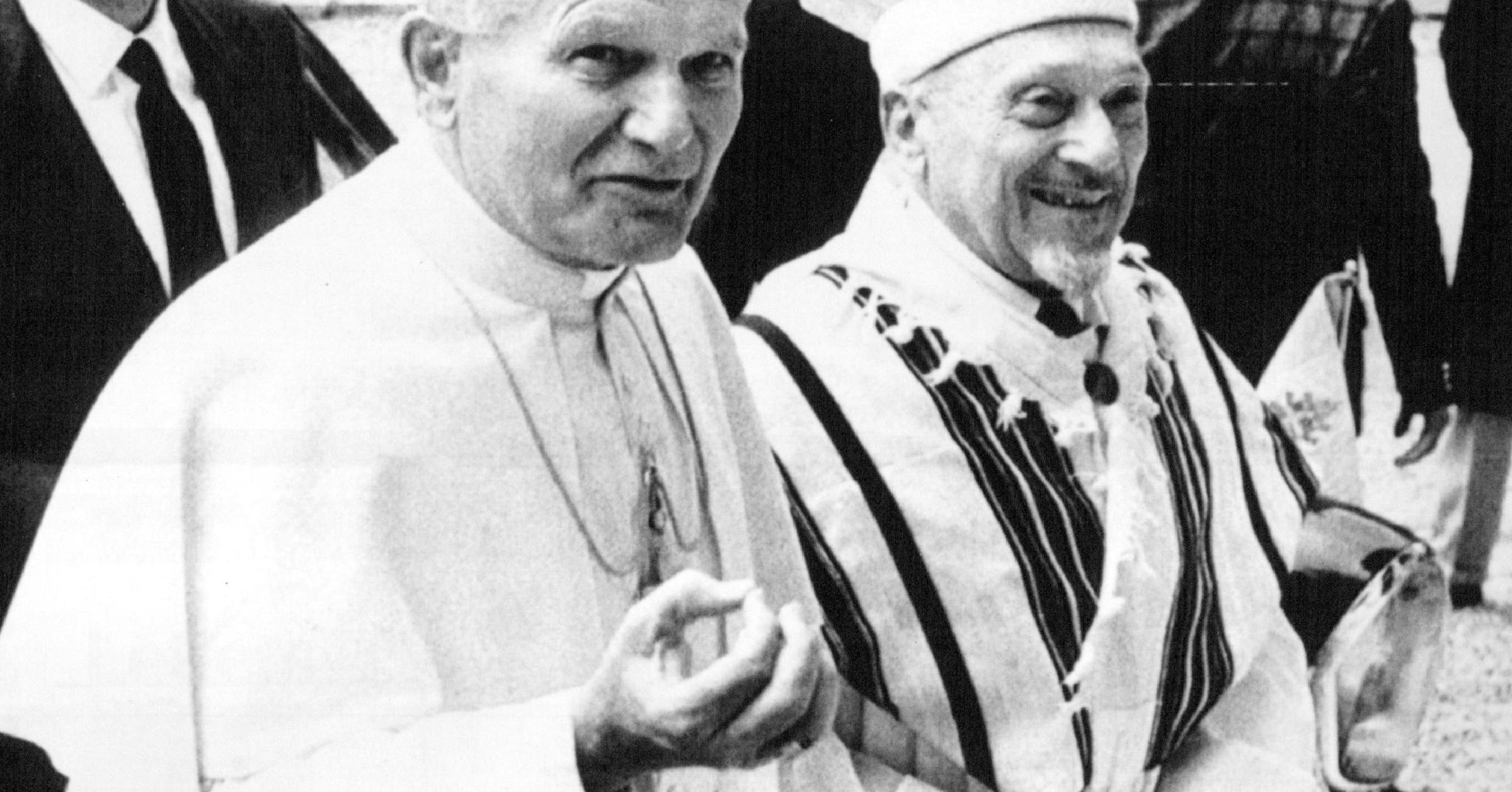

In October 1945, leading Minneapolis rabbis issued a public appeal to “the Christian conscience,” mourning that millions of Jews had perished “because of indifference.” Two decades later, the Catholic Church responded in a remarkable way — with the 1965 promulgation of Nostra Aetate, the Second Vatican Council’s “Declaration on the Relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions.” The document marked a turning point. For the first time, the church explicitly condemned antisemitism, rejected the false charge that Jews were collectively responsible for Jesus’s death, affirmed the enduring covenant between God and the Jewish people, and called for friendship and dialogue among all faiths. Nostra Aetate opened a new era in which Jews and Catholics could meet not as adversaries in theology but as partners in seeking human dignity and divine truth. At the time, Jewish leaders greeted the declaration with both hope and caution. The local Jewish newspaper hailed it as “a great blast of fresh air,” while Joachim Prinz, president of the American Jewish Congress and a refugee from Nazi Germany, warned that its meaning would be proven only “by the manner in which Catholic parishes carry it out.” Sixty years later, both perspectives remain valid. Nostra Aetate invited the church to self-examination and renewal. Pope John Paul II became the first pope to visit a synagogue, recognize the state of Israel and pray at the Western Wall. Pope Benedict XVI reaffirmed that Jews bear no collective guilt for the crucifixion. Pope Francis, who called the declaration “a genuine gift of God,” urged the faithful to build a culture of encounter — “a culture of friendship, a culture in which we find brothers and sisters, in which we can speak with those who think differently, as well as those who hold other beliefs.” Yet six decades later, Nostra Aetate remains both milestone and mirror. Its words continue to inspire, but they also remind us how far the world has yet to travel. Antisemitism, Islamophobia and other forms of religious prejudice persist across political and cultural lines. Nostra Aetate was never meant as a final word but as an opening: a summons to humility, to ongoing dialogue and to the hard work of conversion of heart. As Pope Francis and Rabbi Abraham Skorka wrote in “On Heaven and Earth,” “What every person must be told is to look inside himself.” In that same spirit, our community will commemorate the declaration’s 60th anniversary Nov. 3-5, welcoming Rabbi Skorka as scholar-in-residence. The Jewish Community Relations Council of Minnesota and the Dakotas joins the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis; the Jay Phillips Centers for Interreligious Studies at the University of St. Thomas and for Interfaith Learning at St. John’s University; and the Encountering Judaism Initiative at St. Thomas in hosting this event. Rabbi Skorka and Archbishop Bernard Hebda will speak together at a community dinner marking six decades of Nostra Aetate. Rabbi Skorka and Pope Francis, lifelong friends, often stood side by side as living symbols of this transformation. In 2015, they paused together at the statue “Synagoga and Ecclesia in Our Time” in Philadelphia, depicting Judaism and Christianity in mutual respect, holding the Torah and the Gospels. Its inscription captures the hope born in 1965: “There exists a rich complementarity between the Church and the Jewish people that allows us to help one another mine the riches of God’s word.” Much has changed since Minneapolis rabbis challenged the Christian world in the shadow of the Holocaust. Catholic-Jewish relations are now defined by dialogue, learning and shared moral purpose. Yet Nostra Aetate continues to call us to vigilance and renewal — to ensure that this progress is never taken for granted and that friendship across faiths continues to deepen.