Copyright MassLive

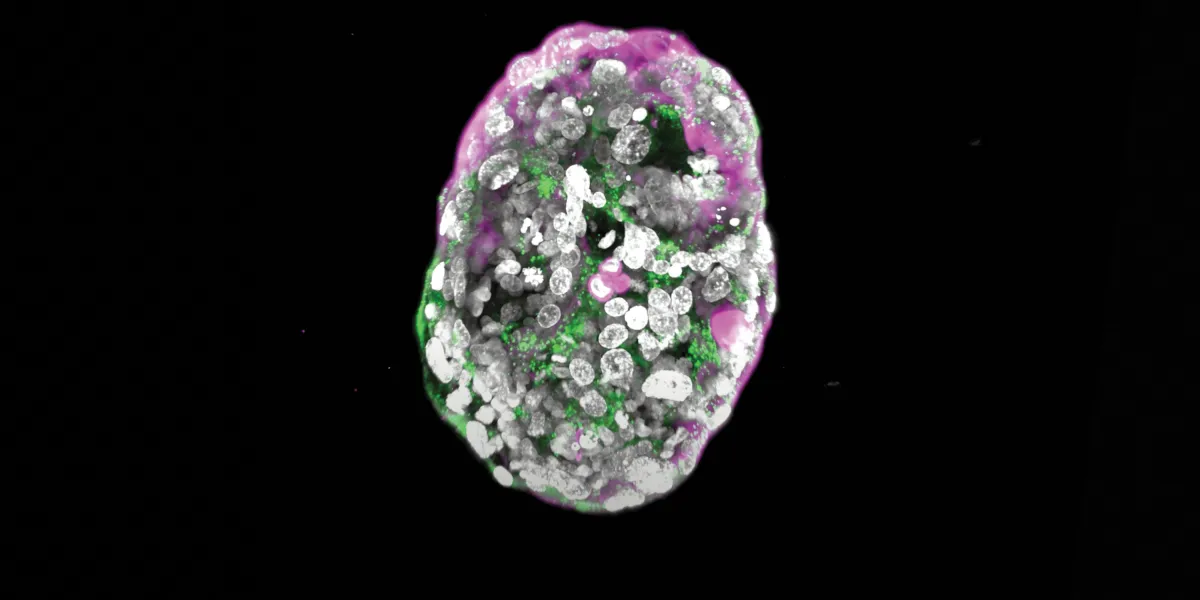

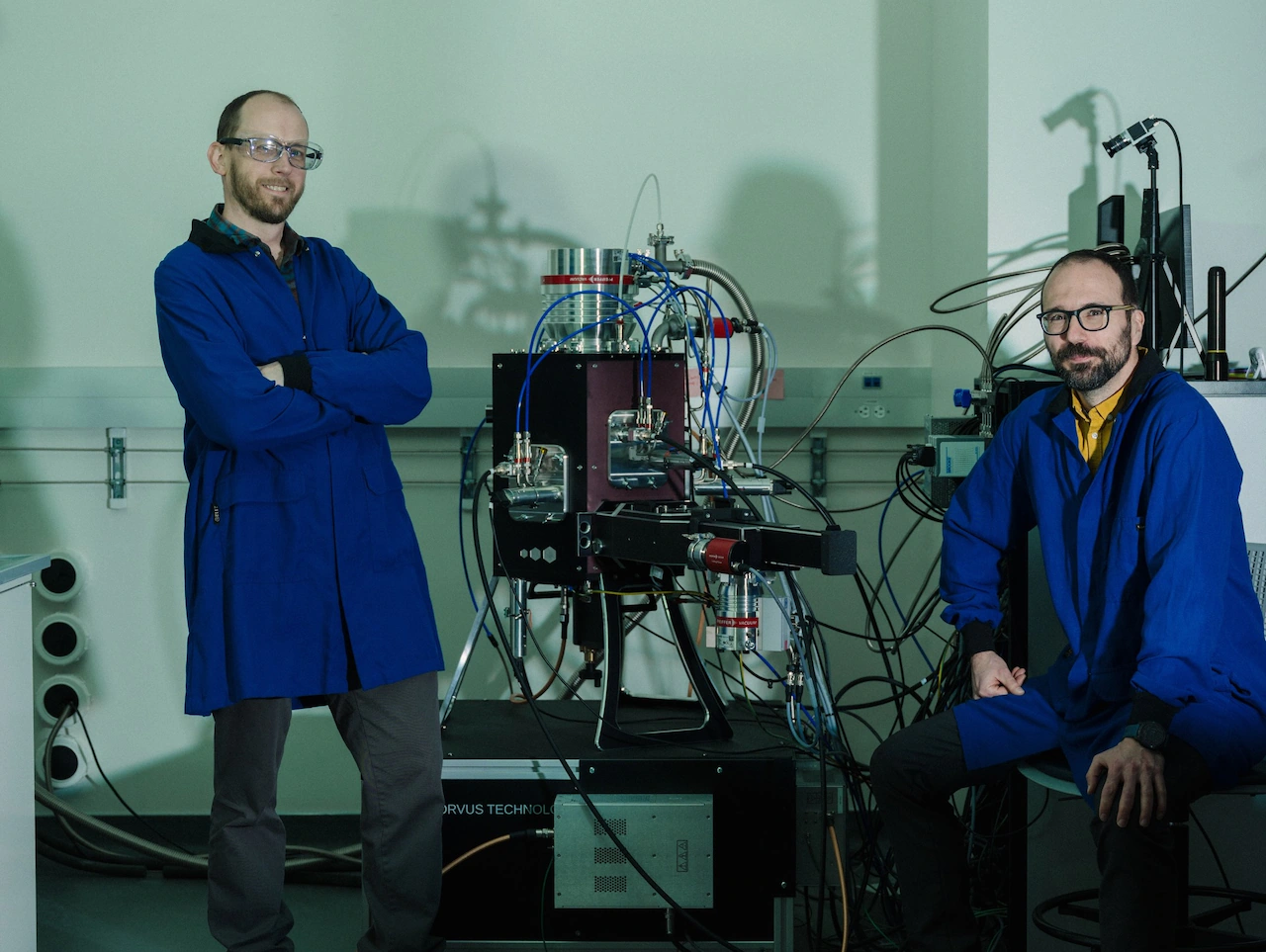

Veterans of the biotech business sometimes talk about surviving various “winters” for their industry — periods when funding drops and companies cut jobs or shut down entirely. They’re living through a bitterly cold stretch now, with recent layoffs at companies such as Takeda Pharmaceuticals, BioNTech, and Arena BioWorks, all of which have Massachusetts sites. But there are some sudden sprouts of hope, with $1 billion in new funding announced last week by just two Boston-area startups, Kaleira Therapeutics in Waltham and Lila Sciences in Cambridge. I also spoke to a first-time founder, Jean Pham, who is in the process of closing a smaller funding round for her Charlestown-based startup, Cellens. Here’s what they’re working on. A pill for managing obesity, developed and tested in China The biggest of the recent funding rounds — $600 million — went to Kaleira, a company that had also raised $400 million last October. It has two key products: an injectable weight loss drug that could prove more effective than those already on the market, and a once-a-day pill that Kaleira CEO Ron Renaud said could help people who’ve hit their target weight stay there. Those two drugs were developed and tested on patients with obesity and Type-2 diabetes in China, by a company called Jiangsu Hengrui Pharmaceuticals. Kaleira has licensed the products from Jiangsu Hengrui, and will work to get them approved in the U.S. and other countries. Why is the company bringing in a drug that was developed in China? Renaud said China has been focused for the past decade on ensuring that drugs developed inside its borders are tested in accordance with global regulatory standards, so that results from clinical trials are considered reliable. “When you take that and then you combine it with the speed and lower expense to do things in China, it really makes them a tremendous partner ... They can move quickly. They’re incredibly innovative,” he said. Renaud said the company had about a dozen employees a year ago. The company has since grown to about 140 employees, who work in Massachusetts and a second office in San Diego. Some employees work remotely, Renaud said. But while the company has leased office space in Waltham, it doesn’t have a lab for running experiments, since all that research and development work was done in China. “This is the first company I’ve run that doesn’t have a lab,” said Renaud. The company plans to manufacture its products in the U.S. to avoid potential tariffs on imported drugs. Artificial intelligence and robot-run experiments Lila Sciences was hatched in the Cambridge offices of Flagship Pioneering, an investment firm that helps to incubate new companies. Flagship is probably best known for launching Moderna Therapeutics, the Cambridge vaccine-maker. Lila has an ambitious vision: creating a new kind of highly automated lab that will leverage artificial intelligence to design and run scientific experiments. The company is focused not just on developing new medicines, but tackling challenges in other industries such as energy and materials development. The company announced this month that it had raised $350 million from a group of investors including Flagship, NVIDIA’s venture capital arm, and IQT, an investment firm created by the Central Intelligence Agency. (It has raised $550 million in total.) Lila Chief Executive Geoffrey von Maltzahn said the company believes that AI models trained on the right kind of data sets will be able to solve lots of unsolved problems, by running scientific experiments faster than ever before. He said a properly designed AI system “could be like a polymath across all materials, chemistry and life science, and become super-intelligent … by doing what every scientist around the world and throughout human existence has done, which is to model the world, design experiments, test hypotheses, run those experiments, interpret the results and keep going.” Von Maltzahn doesn’t think that will render human scientists obsolete, but instead free them from grunt work — what he calls the “the 99% of Edisonian perspiration, [like] pipetting small fluids around for years on end.” Creating this kind of new AI-fueled “science factory,” if it works, could be “the ultimate competitive advantage in science, and therefore it is critical that the US and our allies win this,” von Maltzahn said. The company currently has 230 employees, and another 50 open roles listed on its website. Lila recently leased a large office in the Alewife section of Cambridge — one of the biggest biotech leases of 2025. It also has an office in San Francisco, and plans to open another in Europe soon, von Maltzahn said. Lila’s chief technologist and chief scientist, Andy Beam and George Church, are both highly regarded professors at Harvard University. Better cancer diagnostics Cellens is developing a new technique for detecting cancer. The startup is first focusing on identifying recurrences of bladder cancer by testing urine — rather than relying on a current test that is more invasive. Jean Pham, the company’s CEO and co-founder, said Cellens is in the midst of completing a financing round this month. She called it an “incredibly tough market” for fledgling companies hunting for their first few million dollars. The technology, initially developed at Tufts University’s School of Engineering, uses machine learning, a form of artificial intelligence, to spot cancerous cells in a urine sample. How? With a device called an atomic force microscope, and a “very sharp probe” that “acts like a nano-scale finger,” Pham said. This tiny finger touches the surface of cells. “It turns out that cancer cells do have very distinct physical properties compared to normal, healthy cells,” she said. Pham said the company, which has eight employees, got a sweet deal on lab space in Charlestown, given the high vacancy rates in greater Boston. Looking ahead I caught up with four veterans of the biotech industry to ask if they were seeing any signs that this winter was thawing. The most dour of them didn’t want to talk on the record. But he said that until more biotech companies started paying back their investors — by going public or getting acquired — the industry would be hurting. Jonathan Gertler, CEO of the consulting firm Back Bay Life Science Advisors, pointed to a lot of money that was raised by venture capital firms to invest in biotech in recent years — but is still sitting in their bank accounts. “You can’t sit on that capital forever,” he said. Gertler said this industry downturn “feels better than previous downturns” because of that dynamic. But Gertler said it’s still “a chaotic time, with regard to policy and with regard to the challenges to science,” which include cuts to research funding from agencies like the National Institutes of Health, as well as anti-vaccine messaging from the Department of Health and Human Services. Bigger pharmaceutical companies have started buying biotechs with promising products, observed Anna Protopapas, a director of several Massachusetts biotech companies. (Earlier this month, pharma giant Bristol Myers Squibb paid $1.5 billion for a Cambridge company developing new cell therapies.) Those kinds of deals are a good sign, she said. But while some companies, such as Kaleira, are hunting for Chinese-invented drugs that have shown signs of promise at a bargain price, Protopapas also views China as a serious competitor that is seeking to keep cultivating its own biotech industry, with far cheaper labor and manufacturing costs than the US. That will require US-based companies to find ways to operate more frugally: “I think we have to become much, much smarter about moving things forward in a capital-efficient way,” she said. “Volatility will remain, as the chaos of Washington isn’t likely to go away anytime soon,” said Bruce Booth, a partner at Atlas Venture, a Cambridge venture capital firm. He mentioned the current government shutdown — the Food and Drug Administration isn’t currently accepting paperwork from companies that want it to review new drugs or medical devices — as well as debates around how and whether to change the pricing of prescription drugs. But Booth pointed to a biotech stock index that has been rising since April, and said there’s “lots to be optimistic about.”