Copyright The Philadelphia Inquirer

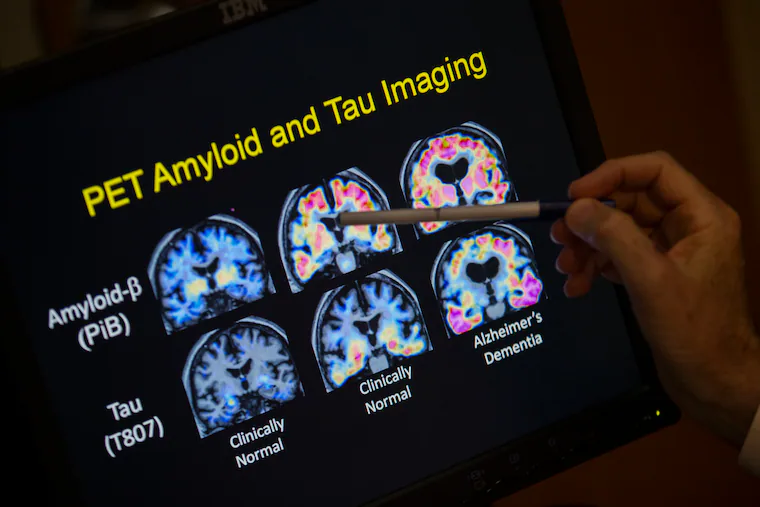

A revolutionary test is transforming dementia care. Days after a simple blood test, a person with dementia can learn whether they have Alzheimer’s disease. At least six companies sell these tests direct-to-consumer; no doctor’s appointment is needed. For a few hundred dollars, an online shopper can order an at-home Alzheimer’s biomarker test. Is Alzheimer’s ready for “direct-to-consumer” testing like COVID and HIV? Our answer is no — not until problems of accuracy, privacy, and access to follow-up care are addressed. Our concerns begin with test accuracy. The FDA guidance for Lumipulse, the first blood test the FDA approved to diagnose Alzheimer’s, emphasizes it should only be prescribed in settings such as a specialty clinic to a patient already showing signs of cognitive decline. This requirement lets a clinician decide whether this test is right for a patient. It also assures a patient that a positive test is truly positive, meaning the person has Alzheimer’s disease. Unlike medications that require a doctor’s prescription, diagnostic tests can be sold without FDA approval, and other blood tests similar to Lumipulse’s are available online. This means a person can obtain a test without any guidance from a clinician. This presents a problem. In the general population, such as the vast number of people who might want at-home testing, the likelihood of Alzheimer’s is much lower. So a large number of test results will be “false positives.” This means, many people whose result is “positive” don’t actually have the disease, and will require stressful and costly follow-up testing. » READ MORE: How to get help if you are struggling with Alzheimer's disease The blood test results also are often not conclusive. The test has three possible results — positive, negative, and “indeterminate.” Up to 20% of people with cognitive impairment tested in a specialty setting will have an indeterminate result and will need more Alzheimer’s biomarker tests. Understandably, a person who feels their memory and cognitive skills are slipping will want to know if Alzheimer’s is the cause. But the high error rate and chance of an indeterminate result are reasons not to take an at-home biomarker test but, instead, to see a doctor. We’re also worried that companies’ marketing language is vague. We’re dementia specialists, and we struggle to understand what they’re selling. Take the blood test to measure ptau217, a protein and key biomarker of the disease. Versions of this test are now marketed by several companies, and are supposed to measure Alzheimer’s pathology. Yet one company’s online description of the test avoids the word Alzheimer’s. Instead, they emphasize “cognitive decline” while marketing the test as an entrée to subscription-paid access to unproven treatments. Testing marketers claim to offer “science-backed” action to prevent symptoms, but their promises are not backed by medical evidence. Another firm amplifies ambiguity when they offer tests such as neurofilament light chain, which measures another protein biomarker. Limited data explain the clinical value of these tests, particularly when measured in the general public. All this vague language seems likely to cause the reader to lose focus on a critical question never raised in the test marketing materials: Are you sure you want to learn about a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s? A positive test result could put a person in legal, financial, and social jeopardy. Laws protect a person with HIV from discrimination, but no such protections exist for a person who is cognitively unimpaired and has a positive Alzheimer’s biomarker test. Genetic nondiscrimination laws protect persons at genetic risk of a disease. These laws don’t apply to persons with a biomarker risk of disease. The websites promoting these tests also don’t discuss how Alzheimer’s and dementia discrimination come in many forms, such as loss of a job, exclusion from a continuing care residence, and friends distancing themselves. Given these risks, the ethical use of Alzheimer’s biomarker tests requires education and pretest counseling. This was the practice in the early years of genetic and HIV testing, and it’s a practice that we and our colleagues have developed for research studies that use these Alzheimer’s tests. Unfortunately, home test providers’ marketing materials don’t promote these messages. Instead, they feature easy access and the value of learning results. Even if the tests were accurate in the general population, the language explaining them were clear, and pretest education was provided, users should be prepared for a positive test to set them on a difficult journey in an unprepared U.S. healthcare system. The nation already faces a shortage of physicians and other providers capable of caring for adults living with dementia. Even fewer are trained to use the new Alzheimer’s biomarker tests. Widespread home testing could lead to scores of people taking Alzheimer’s results to their physicians with questions, with few providers able to handle those interactions. For now, we think the industry of home Alzheimer’s testing is an innovation too far, until these challenges are addressed. Here’s how we would move forward: This is the work needed to ensure that learning your Alzheimer’s risk from an at-home test isn’t so risky.