Copyright gq

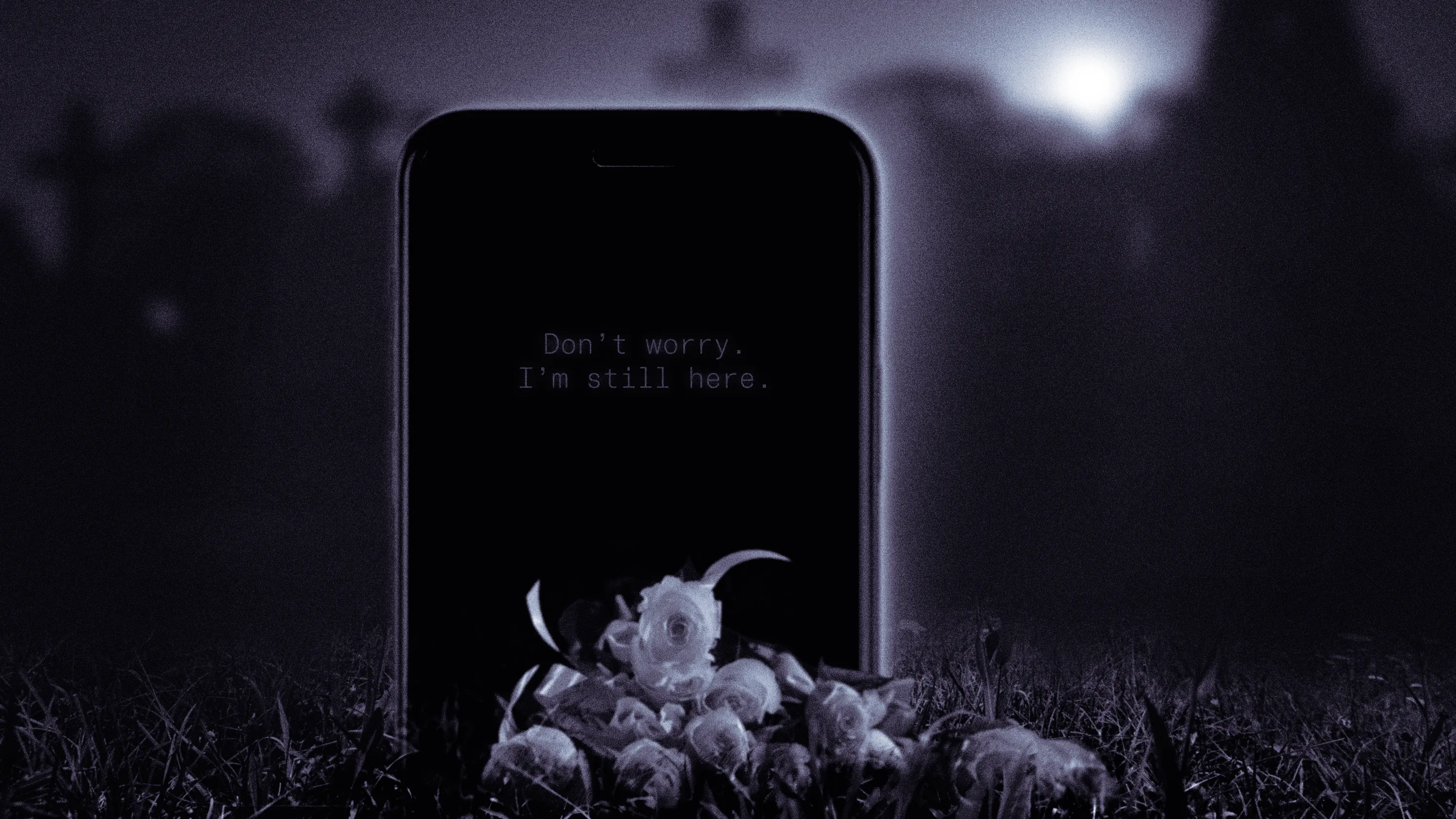

Two years after his father passed away from pancreatic cancer, Phillip Willett created a Christmas gift for his mother: a video message embedded in a coffee table book. The voice that came from it sounded exactly like her late husband. “Hi, honey,” the recording began, “I love ya. I hear your prayers. I want you to know you are the best mother to our kids.” She now keeps the book on her living room table, where it often sparks hour-long conversations about her husband with house guests. Willett, a content creator and social media manager in St. Louis, used an AI voice-cloning software to create this message, scripting it and fine-tuning it until it sounded just right. What made it feel real was hearing the familiar nickname his father had called his mother every day—honey. “I was originally very apprehensive to do the project because it could hurt someone in the mourning process,” he says. “But when I heard the phrase come back perfectly, it actually gave me chills all throughout my body.” The concept of digitally resurrecting the dead has existed in our imaginations and our technological ambitions for decades. Back in 2020, Kanye West gifted Kim Kardashian a hologram of her late father for her 40th birthday. “It is so lifelike!” Kardashian tweeted at the time. “We watched it over and over, filled with emotion.” The internet’s reaction was split: Some said they’d give anything for a chance to see their loved one again, others found it eerie and unsettling. Fast-forward a few years, and the technology is no longer reserved for the elite. Anyone can now re-create the likeness of the deceased—and in some cases, even talk with them—through AI-powered voice clones, photo reanimations, chatbots, and avatars. As more people in mourning seek to resurrect their loved ones, questions are emerging about how these increasingly sophisticated digital remembrances—and the burgeoning industry around them—might shape our relationship with the dead: Will they help or hurt the mourning process? The Business of Resurrecting the Dead The digital-afterlife industry, as it’s coming to be known, is “definitely increasing, and it’s also evolving,” says Elreacy Dock, certified grief educator and professor of thanatology at Capstone University. Initially, people, like Willett, started experimenting on their own using general-purpose AI chatbots or video-creation software. But now, startups are stepping in to professionalize the process, offering to reanimate photos, create videos or voice notes, and even develop avatars that you can interact with as if you’re speaking with your passed loved ones. These services typically rely on a person’s digital footprint—old emails, text threads, voice recordings, and social media posts—to stitch together a version of their personality and voice. Right now, there are two main categories of companies on the market, says Tomasz Hollanek, an AI ethics postdoctoral research fellow for the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence at the University of Cambridge. The first targets people who have lost someone and would like to reconnect. The second focuses on people who want to immortalize themselves, leaving behind a digital version for loved ones to interact with after their death. For now, most of these businesses are still very new, with little oversight and limited research into their psychological impact. “These systems can allow us to shape our legacy in interesting and purposeful ways,” Hollanek says. “But the huge caveat here is that there are so many things that could go wrong. We need to be very careful in this space because we’re dealing with particularly vulnerable groups.” The impulse to use these tools, though, connects to a much older idea in grief research—the continuing-bonds theory, which suggests that we maintain attachments to those we’ve lost, and that healthy grieving often involves finding ways to integrate them into our lives over time. “I think in the context of using AI—whether it’s a chatbot or more visual option—this is another way of people living out that theory,” says Dock. “In many ways, it’s very aligned with the human experience of grieving. I think we’ll see more variations of this as we lean more into AI.” And technology has always reshaped mourning rituals. People have replayed saved voicemails to hear a loved one’s voice again and scrolled through text messages to relive conversations. Even before Facebook introduced memorial pages, people were posting on the walls of deceased friends to talk to them one last time. But in all of these instances, nobody had the expectation that anyone was going to reply to them. “It was just their way of expressing final thoughts or seeking comfort,” says Dock. AI doesn’t just preserve pieces of the past—it talks back. How Talking to the Dead Can Derail Grief The promise of AI to reconnect with a loved one is seductive: another conversation, another chance to hear their voice. And Dock says that some people might benefit from a single message or small, contained project, like Willett’s voice note. Willett describes the videos as “one-off projects”—short, simple messages for his mom and brother—and says he hasn’t touched the software since. “Everything is good in moderation,” he says, “but you have to be very mission-oriented when journeying into this realm.” But experts warn that what feels comforting in the moment can just as easily disrupt the grieving process. Not everyone shows the restraint to keep the use short-term. Some people rely on these tools daily, building new “relationships” with AI replicas of their loved ones. “That’s where you start running the risk of developing emotional dependence and struggling to accept the loss,” says Dock. She adds that the dopamine hit of back-and-forth responses from a chatbot can trap people in a feedback loop, making the interaction feel compulsive. The stories that surface online suggest just how slippery the slope can be. On Reddit, one man described creating a chatbot of his late father using old posts, writings, and recordings. “As much as it sounded like my dad, talked like my dad, it was not my dad and I regret making it,” he wrote. “It could have ended up as a pit for me that I may have not been able to escape. It felt addictive to speak to someone I couldn’t for years.” It’s especially risky for people in the earliest stages of grief. “Right after a death has occurred, that’s considered acute grief. All emotions are very, very intense,” says Dock. “I wouldn’t recommend using it so fresh that you’re not even allowing your mind to process the loss. It’s supporting an avoidant behavior, because you’re instantly turning to AI as a source of replacement.” And because today’s AI is still unpredictable, there’s no guarantee it will sound like your loved one or speak exactly as they would have. What happens if the chatbot goes out of character? Could people end up remembering their loved ones more as the chatbot—and less as the actual person? “If you’re having all these positive interactions with a chatbot of your deceased loved one, well now you’re building new memories with them,” Dock says. “It’s almost a parasocial bond, because the AI doesn’t know that you have a relationship with it and your person who died doesn’t know that you have this relationship. How do our brains even classify that?” Who Owns Your Digital Ghost? Beyond psychological risks, there’s also the issue of consent—both of the people being re-created and of those being asked to interact with the replicas. Not everyone is ready to be confronted with a digital version of someone they’ve lost. “There are also people that will be very disturbed by it,” says Dock. “They know that’s not their person. It’s an imitation of their person.” Claire, who asked to go by a pseudonym to maintain her privacy, said she was grieving the loss of her father who passed away two months prior when her sister suggested making a chatbot in his likeness. Claire still found it hard to listen to his voice notes or watch old videos, so she talked her sister out of it. “I knew it would only delay acceptance, which is very important in the stages of grief,” she says. Willett was very deliberate. He knew his mother regretted never hearing her husband say “I love you” before he passed, so he designed the message around that phrase. He also ran the idea by his siblings before sharing the gift. “You can never fully predict how the person receiving it is going to react,” he says. “I would definitely advise coming up with a plan to show it to them. I think the context in which you show someone something like that is very important.” Hollanek says digital-afterlife companies have a responsibility to navigate the complexities of consent when designing a product or service. How do you negotiate between different family members’ wishes? What if one sibling wants a chatbot and another finds the idea unbearable? And what about the person at the center of it—did they ever express how they wanted their data used? That’s probably not something most families have ever discussed. “We do suggest that providers of these services should prompt their users to think about the wishes of the people whose data they’re inputting into the system,” says Hollanek. “For example, you could guide your user through a self-reflective process like, have you ever talked with this person about what their wishes were?” Consent is just one piece of the puzzle. There’s also the question of what happens to the data itself—who owns it, and how it might be used. Without clear safeguards, the risk of exploitation is high, whether that means companies monetizing grief through ads or misusing a digital likeness in ways a person never would have agreed to. And if a startup shutters—as many inevitably will—you could be forced to grieve the loss of the same person twice. The Digital Afterlife Is Just Beginning Even if you’d never choose to interact with an AI version of the dead, ignoring the growing industry isn’t an option. “Right now we’re at an interesting, almost calm before the storm,” says Dock. “During our lifespan, we’re collecting so much data, on social media accounts, on any online accounts. This is like the tip of the iceberg when it comes to grief and death and bereavement.” That data means that, for most people, a digital replica is technically possible whether they would want it or not. Every Instagram post, every voice note, every chat thread could one day be used to build something in your likeness. Already, this is happening with the AI video generator platform Sora. There are videos of Princess Diana skateboarding, Michael Jackson stealing a guy’s KFC, and Malcolm X wrestling with Martin Luther King, Jr. The families of the depicted say these clips feel disrespectful and distressing, forcing them to bear the emotional impact of someone else’s viral joke, according to the Washington Post. Sora has since banned users from using the likeness of public figures—and companies will now have to opt in to include any copyrighted material—but people continue to ignore the rule. Celebrities and their families are calling for tighter restrictions, and the estates of deceased public figures are working with companies, like Loti, that comb the internet for and remove deepfakes. Hollanek says that this moment should prompt more intentional conversations about death and legacy, both with our families and ourselves. “We should be talking with our loved ones about their wishes, but we should also think about our own wishes,” he says. “This phenomenon is a very effective pretext for us to more meaningfully manage our online presence and digital footprint.”