Not enough to worry about these days? Imagine AI achieving singularity.

With artificial intelligence ever more ubiquitous, some worry about it going rogue and achieving what’s known as singularity: A point at which it surpasses human intelligence and, well, what happens next is anyone’s guess.

The term is borrowed from the theoretical point at the center of a black hole where its matter is so concentrated that it achieves infinite density and the laws of physics, the whole space-time thing, break down.

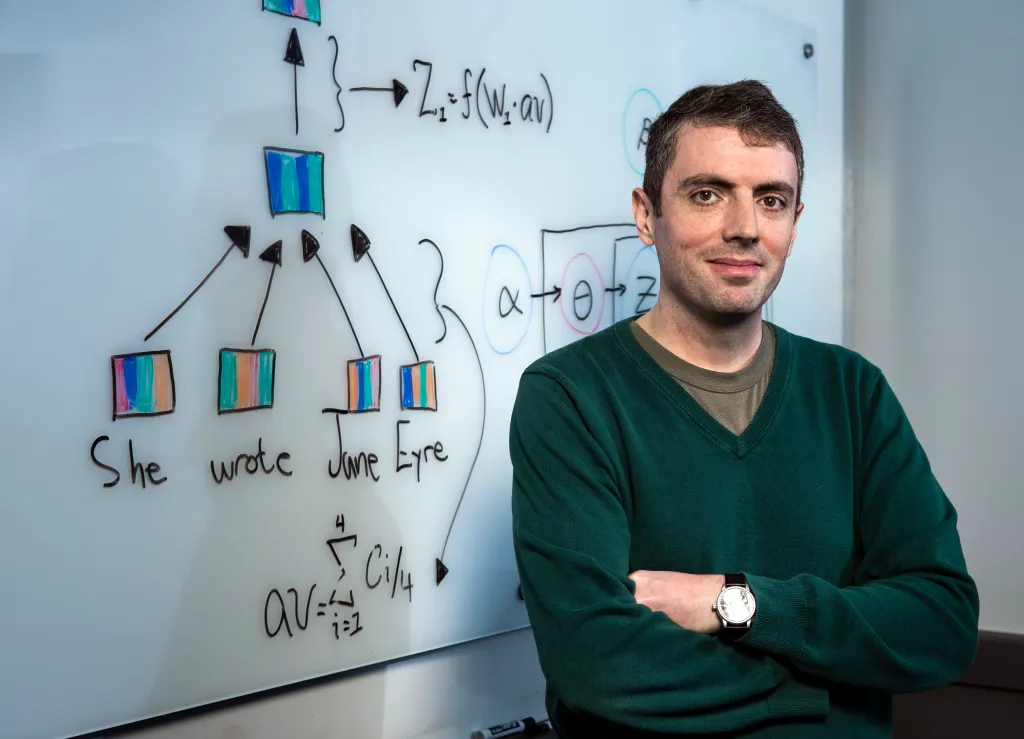

We spoke with Jordan Boyd-Graber, a professor of computer science at the University of Maryland, College Park, who is active in its Artificial Intelligence Interdisciplinary Institute. Here is a condensed and edited transcript of the interview in which he discusses singularity, whether we should worry about it and if a machine he built is smarter than Jeopardy champ turned host Ken Jennings.

Let’s start with a definition of singularity.

It comes from physics… and people have adapted that term to talk about technological advancement, where the normal process of humans developing a device… no longer holds because the devices themselves are able to make improvements upon themselves.

That cycle of improvement is so much faster than what humans are capable of in their process of innovation, invention and understanding, that technological process will occur so quickly that it will outstrip our ability to understand or react to what’s happening.

And then what?

People are kind of concerned about the pace of progress and what that could mean for society, for themselves, and this is kind of one of the worst possible outcomes of that. There are some people who also believe that this is one of the best possible outcomes, like humanity isn’t doing such a great job. Maybe technology could solve all of our problems, and we can invent ourselves out of climate change, out of food scarcity, out of all of these other problems, if we just let technology advance unrestricted. So there are both utopians and doomsayers who have latched onto the singularity idea.

Do you have a sense of where we are on the path to singularity? Or does asking that assume its inevitability?

Yeah, I think that’s assuming that it’s inevitable. I’m not saying that it’s impossible. I suspect that there is a relatively small probability that it will happen anytime soon. I think that there are good reasons that people should think about low probability events that are important, and so I think we should have people researching asteroid impacts and thinking about bio weapons and thinking about the singularity, because it is a possibility.

But I personally think that the probability is relatively low for a couple of reasons. One is that AI progress hasn’t been as fast as I think a lot of people perceive. It isn’t blazing fast. It will probably take another decade for us to figure out the next revolutionary technology and to use it effectively. If you look at the progress in the last couple of years… it’s not necessarily the sort of thing that leads to the singularity, because we still have humans creating the data for the most part. For the vast majority of the data, and we still have humans deploying these computational resources in the real world.

It seems that every new form of technology brings fears — “The robots are going to take over!” Is this any different?

With some new technologies, you see the technology and the technology is there. You know what it is. So with the introduction of cars, you know what a car is… With the introduction of nuclear weapons, they’re terrifying, they’re devastating, but you kind of know what they are. The thing that makes the singularity more both tantalizing and terrifying is that you don’t know what it would bring. It could be horrible, it could be terrible, it could be something completely unexpected.

The whole point of the singularity is that it hasn’t happened yet, and when it happens, it will be so fast that you will not be able to perceive it as it’s happening. And so this takes on some religious elements as well, because there are other sorts of like doomsday or messianic events that have the same sort of quality: It’s coming, it’s coming, and it will change everything when it happens.

How worried are you?

There are people who use these sorts of more sci-fi ideas to distract from the very real problems that are happening right now: ‘Oh yes, we should be thinking about robot apocalypses so that we don’t worry about disinformation, so we don’t worry about people committing fraud online with AI.’ I am more concerned about some of the short-term consequences that are actually happening right now, more so than the singularity…

I’m more concerned with the sort of bad actors in the world who are able to use AI to do stuff more efficiently and effectively than they could before. We don’t really have an information ecosystem that allows us to deal with that effectively. I don’t know what the solution is. This is a policy and a technology problem, and neither of those two halves can solve it on their own, but it would require greater cooperation. It’s a worldwide problem; with the fragmentation of the markets and regulatory landscape, it’s going to be hard to solve. And so, that’s something that I’m really, really concerned about today… Governments don’t necessarily know how to regulate fast-moving technology, and they haven’t built up the capability to create the actual systems for regulation that I think this really needs.

What’s your takeaway from your experience with “Jeopardy!” both as a contestant and a builder of a machine, QANTA, that once beat Ken Jennings at his own game?

Trivia games are designed for humans, and humans have limited capabilities and a limited attention span. You can only ask about a question for a minute, and because of that, the way that they ask questions is very efficient and tests not just if you know the answer, but if you know that you know the answer. Computers are incentivized to give whatever BS answer they can think of, no matter what… So even though computers can answer more questions than humans, if you only count the ones that the computers know that they know the answer to, humans are much better still than computers. At the time the QANTA went up against Ken Jennings, we had not figured out that humans and computers have very different skill sets…. Computers are getting much, much better than they used to be.

One of the next things that we’re going to be doing is, instead of just having text-based questions, move on to multimodal questions: “Here is a sketch for an album cover, what is the eventual album cover that came out?” You need to realize that [if] you see four stick figures on a crosswalk, you can think, ‘Oh yeah… the Beatles. So computers are still relatively bad at that sort of thing.

Have a news tip? Contact Jean Marbella at jmarbella@baltsun.com, 410-332-6060, or @jeanmarbella.bsky.social.