Copyright Forbes

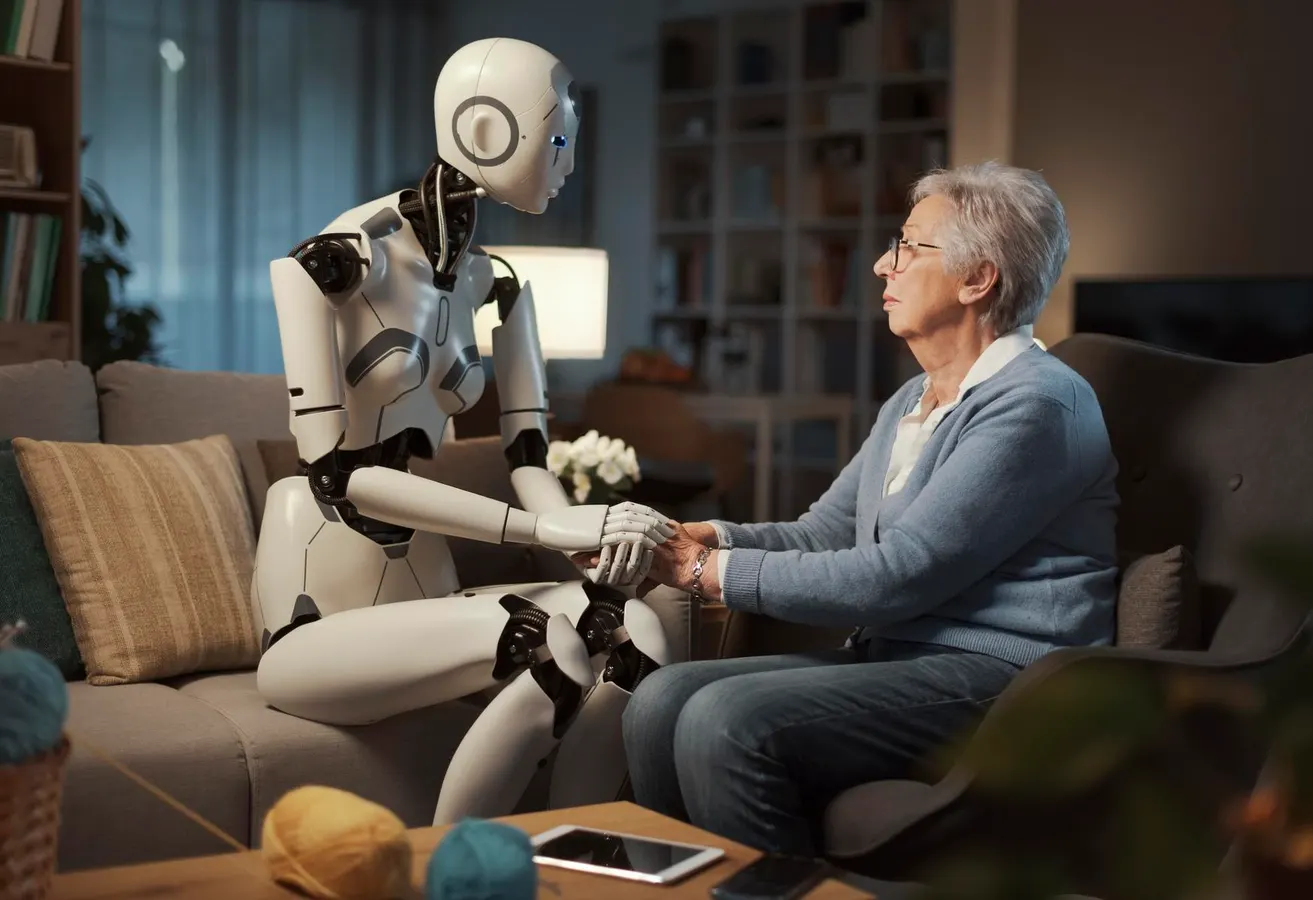

For academics, thought leaders, and other members of the armchair business punditocracy, one thing must be made abundantly clear: a new economic model is not about to arrive and rescue anyone. Capitalism isn’t going anywhere, and it will forever possess muscle memory. EBITDA pressures, pervasive growth targets, private equity investment, analyst expectations, and humongous cash-out exits remain on the scoreboard and will for the foreseeable future. And the investor base? No, it’s not about to wake up tomorrow and begin trading short-term returns for “social purpose” good vibes. Despite the fact that it could do a lot more to save the planet. The responsible path for organizational leaders to contemplate is far more difficult and—ironically—more practical: leaders must evolve how they run businesses within the existing and emerging constraints. That starts by being honest about two elephants already in the corporate crosshairs: AI and demographic change. Add to that the fact that, soon, government intervention might be needed to establish new regulations so companies—whether small, medium, or large—can operate without causing unilateral harm due to the AI or demographic elephants in the room. It may even be why Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell hauntingly described the U.S. labor market in September as follows: “Kids coming out of college and younger people, minorities, are having a hard time finding jobs.” MORE FOR YOU The elephants of AI and demography will be this century’s OPEC oil shocks and stagflation crises—twin forces that force leaders to reprice the operating model within the existing capitalist system itself. The Wobble of Entry-Level Jobs The data does not lie: entry-level jobs are wobbling. The telltale signals have been gathering velocity. Handshake’s late-August snapshot showed college job postings down by more than 16% year over year, while applications per job were up 26%. It is precisely what, as Powell described, a “low-hiring, low-firing” market looks like to a new graduate: few seats opening, minimal churn, and a lot more competition per opening. A recent Stanford study backs this assertion up, suggesting that for 22-25-year-olds, the AI revolution is having a “significant and disproportionate impact on entry-level workers in the U.S. labor market.” If you go beyond the headline and examine the trendlines, you’ll gain a fresh perspective. For example, the aforementioned Stanford study finds that early-career workers in the most AI-exposed occupations experienced a roughly 13% relative employment decline, even after controlling for firm-level shocks. Adjustments were made through employment rather than pay. Pair that with the youth unemployment readout the Bureau of Labor Statistics published on August 27—10.8% in July, one full point higher than the prior summer—and you get a picture that reflects what people are feeling on the ground: the first rung of entry-level jobs is getting narrower, and the career ladder above it is becoming far steeper. It’s no better in the United Kingdom. A recent study from King's College London found that firms with workforces exposed to AI reduced total employment by 4.5% on average, with employment in junior and entry-level roles falling by 5.8%. Furthermore, these same firms became 16.3 percentage points less likely to post new entry-level vacancies. The sharpest declines occurred in technical roles such as software engineering and data analysis. The question is not whether AI is good or bad, but whether leaders will design the labor market so that human learning and employment keep pace with machine capability. It feels like, in most days of late 2025, we are not only losing sight of what business is meant to serve, but some senior leaders are even pushing further, deliberately harming society through large-scale job losses caused by new efficiencies enabled by AI adoption. The 14,000 positions recently terminated at Amazon are just a small part of the one million jobs cut so far in 2025. One million! While it was Peter Drucker who claimed that “The purpose of business is to create and keep a customer,” maybe we need to quickly adapt that line to “The purpose of business is to create and keep a customer through employed human beings.” Companies keep implementing automated and artificial intelligence processes that swallow routine work that juniors and younger workers used to practice. Cutting entry-level roles might lift productivity, but it also deletes the live-fire reps that help people develop the ability to skillfully judge and decide. When Powell mused in September that employers who once hired straight out of college may now “be able to use AI more than they had in the past,” he was describing an incentive structure, not a mystery to be solved. Regarding current-day capitalism, Geoffrey Hinton—sometimes referred to as the godfather of AI—worryingly claimed in September, “What's actually going to happen is rich people are going to use AI to replace workers. It's going to create massive unemployment and a huge rise in profits. It will make a few people much richer and most people poorer. That's not AI's fault, that is the capitalist system.” That does not bode well, however you position it. Strip away the polemic and the point stands. Incentives rule. Capitalism will always be king. That is why the “purpose over profit” sermon rings hollow for so many executives in the age of AI. What we need is a revised form of capitalism, one where purpose is aligned with profit design, not purpose posing as strategy, and where government policy helps set the rules for ethical use of artificial intelligence. According to research from FCLTGlobal, “long-term companies tend to outperform on revenue growth, earnings, and job creation,” suggesting there is a management method to keep the capitalist lights on while building AI guardrails into a revised operating model. What is evident is that capitalism will not reform itself. However, leaders can still extend their thinking and rewire what produces their earnings while keeping people employed. As author Faisal Hoque rightly points out, “AI has the potential to be a great global equalizer—or it could become the most powerful driver of inequality in human history.” Demography Enters the Chat If AI is the first of our two new elephants in the corporate boardroom, we must also acknowledge that several line items of demographic math are simply not adding up. In the United States, the median age reached 39.1 years in 2024, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Older adults are now growing faster than children, and in nearly half of all U.S. counties, the 65-plus cohort outnumbers children. While the labor market ages the early-career pipeline is thinning. It is becoming a structural mismatch, and the rapid ascent of AI—vacuuming up entry-level tasks and jobs—tightens the vise. The demographic undertow—one that far too few leaders are even thinking about surfing—will change the math of hiring, training, development, and succession the way a tide changes a harbor: slowly, then all of a sudden, look out, your keel is scraping the seabed. Wherever you look, demography is rapidly shifting in society, as well as the workplace. In the U.S., births fell again in 2024, with the total fertility rate sliding to roughly 1.59 births per woman, well below the replacement rate of 2.1. The median age of a U.S. worker in 2004 was 40.5, but 20 years later, it had increased to 41.7. Canada mirrors the pattern with a record-low fertility rate in 2024 of 1.25 and a median age just under 40, and rising. Immigration might prop up the population, yet the intake pipeline remains structurally tight, as the number of children that immigrants either bring into the country or give birth to is equally anemic. The Future If organizations continue to chop entry-level roles in favor of AI and automation, while the raw number of young people dwindles, there will eventually be a wisdom gap. When the base thins, you cannot delete early-career roles and still expect judgment and wisdom to appear by magic. In my experience as a former chief learning officer in tech and telecom, practice produces judgment, and judgment compounds into wisdom. Similarly, a cohort-heavy band of late-career experts who retire en masse (or, as in the case of Amazon, are terminated with the sharp slice of a sword) sees tacit knowledge exit faster than it can be recorded, let alone transferred. From there, middle-aged and mid-career workers quickly become the organizational fulcrum, balancing raising their kids and caring for aging parents, while also bearing the added burden of picking up the slack left by dwindling numbers of young and older workers. And we wonder why rates of anxiety and burnout are on the rise? Artificial intelligence can help fill the void of the coming demographic disruption. But as it is being deployed in its current form, the AI cart is being put before the horse, ahem, human. If leaders want AI to close the demographic gap while meeting capitalist requirements, they must redesign the workflow so humans are not in the loop—they are the loop. You cannot 3D print young people, and you cannot outsource wisdom. Wisdom, of course, is earned experience. The AI genie is not only out of the bottle, it’s quickly becoming the bottle. Leaders should consider redesigning the workplace for an age-aware form of capitalism—and make that both the strategy and its purpose. And if governments aim to reduce large-scale job losses, they might consider implementing AI and demographic guardrails—for example, universal basic income and AI policy—to avoid additional casualties.