Copyright Los Angeles Times

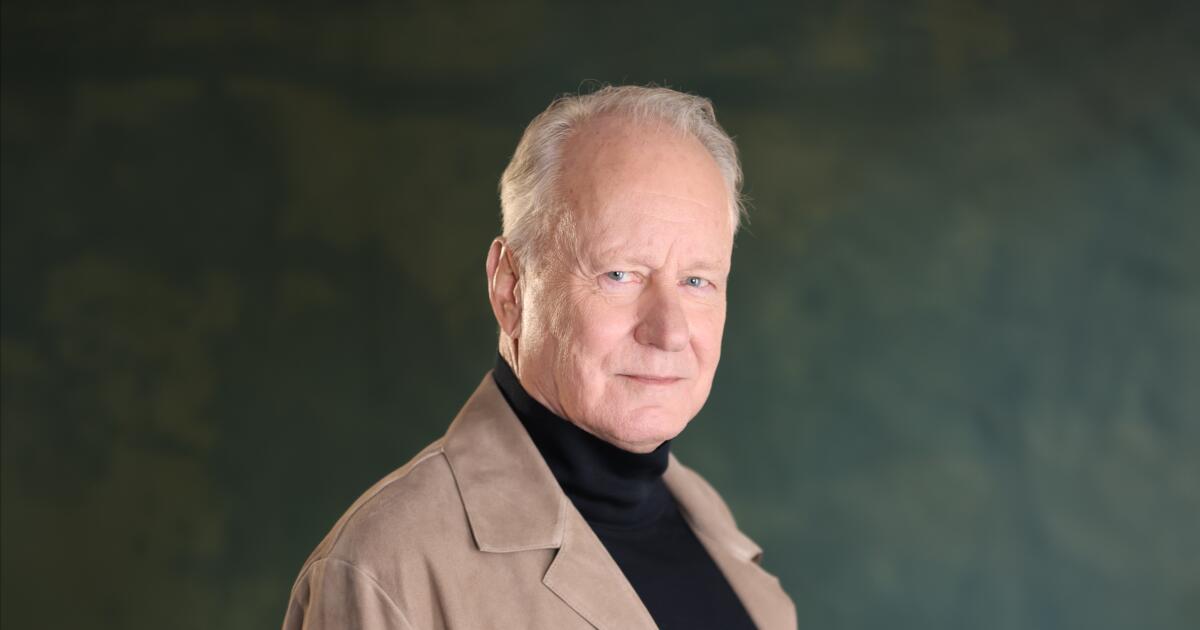

Three years ago, Stellan Skarsgård suffered a stroke. It wasn’t catastrophic but it left him with damage to his short-term memory and focus. For a moment, he was certain his acting career was over. “OK, so this is it,” he remembers thinking. “I’m finished.” The Swedish actor, 74, was then in the middle of the most visible run of his half-century in film and TV, a towering presence in two major franchises, playing the monstrous Baron Harkonnen in Denis Villeneuve’s “Dune” and the rebel mastermind Luthen Rael in the Disney+ “Star Wars” series “Andor.” As soon as the shock subsided, Skarsgård began to look for a way forward. “I said, I think I might be able to do it if I get somebody to read my lines,” Skarsgård says over Zoom from his home in Stockholm. “Because I can’t remember.” At the time, he was between seasons of “Andor” and between the first and second “Dune” films — still in demand but unsure whether he’d ever work the same way again. He called Villeneuve and Tony Gilroy, the “Andor” creator and showrunner, to explain what had happened and what might need to change. Since then he’s used a small earpiece feeding him dialogue, a difficult adjustment, he admits, but one that’s allowed him to keep working. The effects of the stroke linger, subtle but real. He speaks with the same measured warmth as ever — that deep, lilting rumble that can shift from conspiratorial murmur to amused growl in a heartbeat — but he sometimes loses a name mid-thought. As he recounts the story, he blanks on both Villeneuve and Gilroy. “This is what happens,” he says, almost apologetically. “I cannot any longer have a political argument, which is sad,” he says. “I become a little more stupid and a little more brief, almost getting the point and missing it by an inch.” There’s no self-pity in the observation, just a clear accounting of change. The stroke seems to have stripped away some of his old formality, leaving him more open, unguarded, even amused by his own lapses. That ease runs through his latest film, Joachim Trier’s “Sentimental Value,” a tender, sharply comic drama about a fractured family trying — and often failing — to heal. Opening in theaters on Friday after an acclaimed festival run, “Sentimental Value” stars Skarsgård as Gustav Borg, a renowned, narcissistic filmmaker who reappears in the lives of his estranged daughters after the death of his ex-wife, hoping to reconnect with them by turning their shared history into a movie. Nora (Renate Reinsve), a celebrated stage actor, wants nothing to do with the project — or with her father. Her sister, the more measured Agnes (Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas), tries to keep the peace as old grievances resurface and life and art begin to blur. Trier’s prior film, the Oscar-nominated 2021 romantic dramedy “The Worst Person in the World,” made him an international name. “Sentimental Value,” which won the Grand Prix at Cannes, seems poised for a similarly warm reception and could bring Skarsgård his first Academy Award nomination. A veteran of both Lars von Trier’s provocations and the Marvel universe, Skarsgård plays Borg with a mix of charm, vanity and self-awareness. He seems genuinely surprised by the response. “You can never tell how a film will hit,” he says, “but this one has reached everybody, every generation, every culture. It’s obviously touched something. And it’s remarkable, because in spite of its seriousness, it’s light. It’s like a soufflé with dark specks in it.” With “Sentimental Value,” Trier hoped to bring Skarsgård back to the kind of intimate, emotionally exposed territory that first defined his work in films like his 1982 Swedish breakout “The Simple-Minded Murderer” and Von Trier’s searing 1996 drama “Breaking the Waves,” which brought him international acclaim. “I wanted to offer him a chance at this age to go back to the roots of that dramatic, vulnerable openness that he does so well,” the Danish-born Norwegian director says by phone from his home in Oslo. “We spoke a lot about what kind of man Gustav was — the paradox of someone who can see people so clearly in his art yet be so clumsy and inept in his real life.” That tension between sensitivity and limitation is one Skarsgård knows well. As a father of eight from two marriages, he has long seen parenthood as the most humbling role of all. “I had to defend Gustav, in a way,” he says. “Being a father, which I am, is a very difficult thing to be. To be a perfect father, as we all strive to be, is impossible. So I felt very much for his failure. I told Joachim that I wanted to stress the humanity of it.” He chuckles softly. “Since 1989 when I left the Royal Dramatic Theatre, I’ve spent maybe four months a year in front of the camera and eight months changing diapers and wiping asses, being with my kids. So I haven’t lacked time. But is it enough? I don’t know. I have eight kids and they all have different needs. Whatever you do, you’ll fail. But you live with it.” The film, he says, captures a helplessness he recognizes. “All those scenes with the sisters, he’s trying so hard, and he really f— up. He doesn’t have the tools for that. But it’s not that he lacks sensibility. He’s a filmmaker, he’s tactile and sensitive. I think a lot of filmmakers have that in common. It’s easier to be vulnerable and soft in your profession than it is in private life.” For all of Gustav’s bluster and ego, the film leaves room for grace. “Maybe there’s an opening, maybe there is forgiveness and maybe there’s understanding — or the beginning of understanding,” Skarsgård says. “I look at my parents. They were very flawed, but I forgive them. They were human.” Learning to act with an earpiece — hearing his lines fed to him while still listening to his scene partners — became its own test of concentration and humility. “I thought it would be easy,” Skarsgård says. “But you can’t have the rhythm of the scene affected by it. The reader has to say my lines in a very neutral way while my co-player is saying their lines at the same time, so you get both lines at once. It’s tough but it works most of the time, I think.” On “Sentimental Value,” the long stretches of unspoken feeling in the script by Trier and the director’s longtime co-writer Eskil Vogt turned out to suit Skarsgård perfectly. “As an actor, you really appreciate when a director is searching for the wordless expressions and the subtleties,” he says. “In a less and less subtle world, it’s necessary to find your way back to that.” Skarsgård has long been one of cinema’s quiet constants, moving easily between Hollywood spectacle and European intimacy. A longtime collaborator of Von Trier, with whom he has made six films, he’s balanced roles in more commercial fare like “Pirates of the Caribbean” and “Mamma Mia!” with riskier, more searching work, including HBO’s “Chernobyl,” which earned him a Golden Globe. “I’ve hedged my bets,” he says with a dry smile. “I have [fans] from small girls to old farts.” He spent decades resisting polish. Early in his career, working with Swedish director Bo Widerberg, a pioneer of realism, Skarsgård absorbed a lesson that never left him: “‘I know you know how to do this,’” he remembers Widerberg telling his cast. “‘But I don’t want to see your f— tools.’” Skarsgård smiles. “I’ve made 150 films. I have the tools. But I don’t want to show them. I want to surprise myself and lose my footing. That’s when new things happen.” Like Gustav, Skarsgård comes from a family steeped in performance: Six of his eight children, including Alexander, Gustaf, Bill and Valter, are actors. Call them a dynasty if you like — or, in today’s less charitable parlance, a “nepo family.” Skarsgård himself treats the whole idea with a shrug. “How could I steer them away from something I love myself?” he says. “I didn’t push them, and I didn’t help them either. I let them decide for themselves. They saw that I was having fun in my life and they were drawn to that.” Still, he insists, there’s no mentoring across generations. “You can’t,” he says. “When I was young, I was protesting the war in Vietnam and my parents’ generation didn’t understand why. I realized then: They knew more about some things, but they didn’t understand the world we were living in. It’s the same now. Young people have to build their own world out of the shambles we leave behind.” For all his talk of generational independence, the family connection still runs deep. At this year’s Telluride Film Festival, Skarsgård was there with “Sentimental Value,” while his eldest son, Alexander, best known for “Big Little Lies,” “Succession” and “The Northman,” was also in town with the Cannes-lauded erotic biker drama “Pillion.” After the “Sentimental Value” screening, Trier watched as Alexander, eyes wet with tears, approached his father. “There was this serious moment,” he says, “and then Stellan just said, ‘Now that’s how it’s done.’ They both broke into laughter and hugged.” When his other children saw the film, it hit them just as hard. “My second son said, ‘You’re so great in it. I hope you recognize yourself.’ I said, ‘F— you, what do you mean?’” He smiles. “Of course he’s seen that thing in me, the artist who’s failed as a parent because he’s too obsessed with his art.” His youngest, Kolbjörn, just 13, “cried so much,” he adds. “He took it very personally, but in a good way.” Over the years, Skarsgård has watched the business shift around him. “Theaters have been bought up and butchered,” he says. “But I still think there’s a need for film, maybe even a bigger one now. People are bored with their noses in their phones. They long for concentration, for a communal experience. But of course, in Sweden too, Netflix and the streamers have taken over and they’re making fewer films and more reality shows. The power of money is always disgusting.” These days, his criteria have shifted slightly. “I want roles that are sitting down — or maybe lying down,” he jokes. “I’m a little more picky now. But the market’s more picky too. There are more Alzheimer’s parts for me and fewer first lovers. My naked body doesn’t sell as much. The real problem,” he adds, getting serious, “is that there just aren’t many good scripts. Most of what you read, you think: I’ve seen that film.” He recalls something Von Trier — with whom he has made such fiercely original films as “Dogville,” “Melancholia” and “Nymphomaniac” — once told him. “Lars said, ‘I make the films that haven’t been made.’ And I said, ‘Yes, you’re right. They haven’t been made. None of them.’” Both “Andor” and “Dune,” he notes, unfold in worlds ruled by vast, oppressive empires, and in a moment like this, amid fears of rising authoritarianism, he’s well aware of the resonance. “I don’t think you build new worlds or tear down old ones with a film, but you can point things out to people, discreetly,” Skarsgård says. “When they realize something is wrong, when they decide to do something about it and what they do — that’s what audiences can pick up on most.” At this stage, Skarsgård says, the real work lies in keeping the craft alive. “In some ways it’s easier,” he says. “You don’t spend a lot of effort on bulls—. You learn to avoid that. But to get it really where it should be, that’s a balancing act. It’s dangerous — and that’s where you want to be — but it’s also a gold mine for an actor.” Asked if he ever considers retirement, he scoffs. “They’ll have to carry me out,” he says. “I like being on set, with the actors, the crew, the director, inventing things together. Play. That energy — I don’t want to miss it. Because that would be missing out on life.” The words come evenly to him, with firm conviction. Whatever else may have changed, the impulse that’s guided Skarsgård all his life — to keep creating, to stay alive to the moment — remains intact.