Copyright thehindu

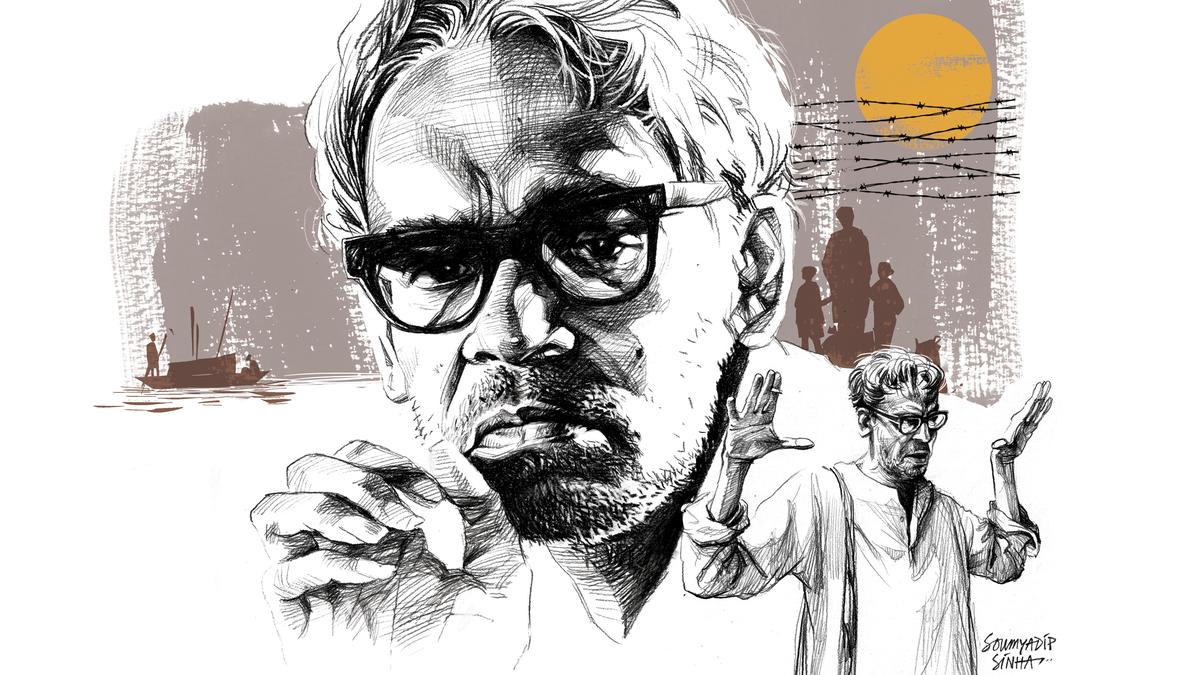

Amongst the great trinity of Bengali Cinema, Ritwik Ghatak was the youngest, the other two being Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen. He lived a short and reckless life, burning it on both ends. His passion and commitment to cinema were as intense as his political beliefs. Even his close comrades could not contain the extra-revolutionary ideas he was obsessed with, and eventually he was left with no choice but to pursue his ideology all on his own. Ghatak was a born iconoclast. And he came to be known as the enfant terrible of Indian cinema. In perfect unison with his life and work, he died comparatively young, in his early 50s. His life and contributions have been unique. There were no parallels; he had no competitors, not even imitators. Starting with Bari Theke Paliye (1958), each of his films was a testament to his uncompromising spirit and ceaseless struggles. It was in 1963, my second year at the Film Institute of India, that he joined us as the Vice Principal and Professor of Film Direction. We had heard about his incredible adventures (in theatre and cinema) and his accomplishments, and were in awe and admiration. Naturally, we were looking forward to watching his films and listening to him. When it happened, we were thrilled, excited and enthused. He never fought shy of speaking about his films. He would tell us why he broke the basic rule of observing the imaginary line that helps keep the gaze of the characters in the right direction. We also came to learn from him the potential of sound to enhance the effect of a particular scene and add new dimensions to viewers’ perception. His uncompromising and passionate approach to filmmaking, as expressed in his extensive and in-depth discourses, was the most impressive and rewarding aspect of his teaching for us students. Equation with Ray Luis Buñuel, the Spanish-Mexican filmmaker, was Ghatak’s favourite and he was an admirer of his 1959 film, Nazarin. He did not seem to appreciate Swedish director Ingmar Bergman. He was dismissive about his religiosity. Once when he screened Ray’s film, Aparajito, in the classroom, he pointed out certain sequences to say, ‘Here is great cinema!’. This turned out to be a revelation to us who had been under the wrong notion that Ray and Ghatak were adversaries. Far from it, the truth was the two had great admiration for each other. It was a closely guarded secret that it was Ray who recommended Ghatak to Indira Gandhi, the then Minister of Information & Broadcasting, for appointment to the Institute. Ghatak elicited appreciation from Ray too, as opposed to what was commonly believed and propagated. Ray once told me, “Ghatak is someone who has cinema running in his veins.” Not a small compliment from a person unfairly pictured as an adversary. In this context, I am reminded of a painful incident Ray narrated to me once. On learning about Ghatak’s death in a hospital in Kolkata, Ray went to pay his last respects. As he came out of the hospital ward where the body was lying in state, a group of young people waiting in the veranda pointed their fingers at Ray and shouted, ‘You killed him.’ Art of melodrama Ghatak’s deep knowledge of the Vedas and Indian culture and tradition found many an admirer among us. Bengal’s partition and the scale of human tragedy it precipitated became a recurring theme and obsession of his films. People, the common lot, always identified him with alcoholism. But there was not a single instance of him coming to the classroom in an inebriated condition. I used to feel impressed seeing the new books he always carried in his hands. Ghatak’s cinematic exercises were unique in their erratic charm, conceptual originality, untamed creative energy, and incisive observation of everyday life. His pervading preoccupation with the ‘mother cult’ set them apart. Ghatak’s uniqueness also lay in his mesmerising talent to transform melodrama into high art. His use of visuals and sounds were totally unconventional. In fact, he carried over a few practices from theatre (his active involvement in the famed Indian People’s Theatre Association is well known) and used them in ways hitherto alien to cinema. A scene or a sequence can be ‘pictured’ strictly following a written script and carry forward an idea convincingly. But Ghatak handled the same scene in stark contrast to the commonplace practice. He would fill it with urgency and feeling by using unfamiliar angles, lenses, lighting, compositions, and above all, jump-cuts while smooth transitions were the norm. Sound also played an important role in his filmmaking. It was given as much importance as the visuals. His use of sound was not just meant to suggest the atmosphere of the place of action but to elicit a dramatic impact. His soundtracks were rich with layered sounds, suggestive and reflective sounds, music and dialogue enhancing the impact of the visual narration and the theme in general. He composed his unique music himself. Among disciples and apostles Of the eight films Ghatak made, my favourites are Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960), Subarnarekha (1965), and Ajantrik (1958). Bimal Roy’s 1958 film Madhumati, the story and script written by Ghatak, is an all-time classic of Hindi cinema. Everything about it is memorable and beautiful. The story, particularly the twist at the end, the casting, songs, the passionate and tragic romance, the valley locale — it was the great combination of two outstanding filmmakers, Ghatak and Roy, that did the magic. As I recall the old days, I realise that the admirer in me did not have a personal relationship with Ghatak. I had never met him outside the classroom. Maybe, it was because I was too shy to form a relationship with my hero of a filmmaker. There were my juniors, Mani Kaul and Kumar Shahani, in particular, who kept themselves close to him as they identified themselves as his faithful disciples and his ‘apostles’. Strange as it may look, none of Ghatak’s films participated in any international film festivals during his lifetime. Nor did he travel abroad. All the same, several retrospectives of his films at international festivals followed his early and untimely demise. It was a decade after I passed out of the Institute that I shared a film festival stage in New Delhi along with Ghatak and his close disciples. I thought I must pay my respects to my teacher and walked up to him and introduced myself, “Sir, I was a student of yours at the Institute. Do you remember me?” He looked up at me with a vague expression and replied, “No.” And that was it. The writer is an internationally renowned filmmaker.