Copyright The Boston Globe

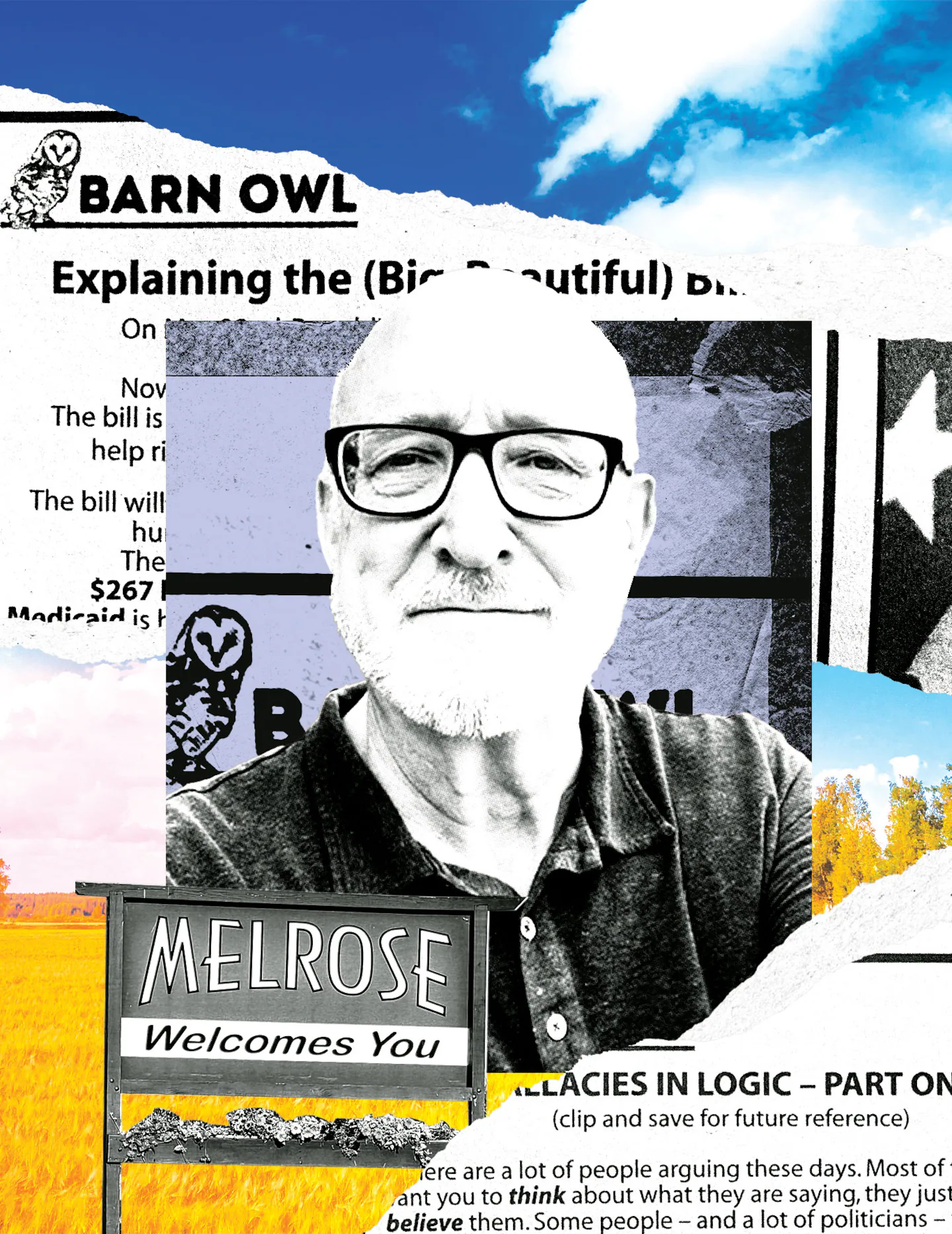

Rather than toss and turn at night, Boardman, 68, opted to resist in an unconventional way. Every week, he decided, he’d purchase six column inches of ad space in the local “shopper” paper that’s delivered free to every resident of his rural county, where Trump got 60 percent of the vote last November. Since early this year, Boardman has used this space to run his own column, about 400 words long, which he calls the “Barn Owl.” Wedged between puppy classifieds and excavator ads, the column — written in simple, accessible language — explains Trump administration moves and other current events from a liberal standpoint, from Medicaid cuts in the One Big Beautiful Bill to DOGE’s push to kick Social Security recipients off the rolls. Boardman started his column just hoping to reach his neighbors. But as feedback and interest rolled in, he realized the column could become a blueprint for piercing the red media bubble that surrounds so many small and rural communities. Research suggests his instinct is on target: Echo chambers that train members to shun outside views can be disrupted when someone those members trust — say, a longtime town doctor — offers them an alternate perspective. For any concerned citizen living somewhere with a free weekly shopper, all it takes to emulate Boardman’s approach is a few hours of writing time and a modest stream of income or donations. “It’s putting your money where your mouth is,” he says, “just saying, ‘OK, we’ve got to become a voice here.’” Boardman grew up in Madison, Wis., and served as an EMT in New York City before heading to medical school and specializing in family medicine. He repaid his medical school loans by working for the Indian Health Service, ultimately serving as medical director of two IHS clinics. Boardman now lives in his wife’s hometown of Melrose, Wis., population around 500, and has embarked on what he calls his “retirement cycle,” pulling about 15 urgent care shifts a month in the small city of Onalaska, Wis. That leaves him with enough free time for volunteer gigs. Since the Obama years, Boardman has watched his home county of Jackson trend steadily redder, like other rural communities around the country. He thinks the shift can be explained partly by conservative echo chambers that have formed in those areas and partly by people’s perception that the Democrats have abandoned them. This winter, as Boardman considered how to reverse the trend, he was inspired by a local voice on the other side of the aisle. For years, an area pastor had been buying ad space to run his own column in the county’s paper of record, the Jackson County Banner Journal. Though the column’s topics varied from politics to Scripture, the pastor’s consistency was what stood out to Boardman. “Just by being there, he is coloring the culture of the county,” he says. Boardman realized he could use the same approach in his own, more progressive column for Jackson County residents. He thought the name “Barn Owl” would resonate with his rural neighbors, while conveying a sense of watchfulness. In addition to placing his ad-articles in the Banner Journal, a subscriber-only paper, Boardman bought ads in the Banner Journal’s offshoot shopper publication, all for about $200 a week. Because everyone in Jackson County gets the shopper, he figured his potential audience would be far larger. Boardman often uses his six column inches to expose the dangers of Trump administration policies, whether or not readers are looking to hear about them. One of his columns focused on Ned Johnson, a man who lost his Social Security benefits after DOGE wrongly declared him dead, and explained why other beneficiaries were also at risk. Another ran through examples of public institutions under threat: city hospitals, public radio and TV, public schools. Under Trump, Boardman wryly concluded, “the public has become enemy number one.” Boardman also likes to give readers the historical context behind news stories. In one column about Trump sending the National Guard to large cities, Boardman discussed the 1878 Posse Comitatus Act, which forbids the US military to take on domestic police duties without authorization from Congress. Once the “Barn Owl” had been running for a few weeks, Boardman started getting some unexpected feedback. “I was getting calls from the Democrats — ‘Ben, what are you doing?’” As it turned out, readers had been approaching local party leaders and thanking them for the column, not realizing it was Boardman’s independent effort. Soon community members were pitching in to cover weekly ad-space costs. (He also republishes the columns on his Substack.) Efforts like Boardman’s may seem to have little hope of piercing well-funded right-wing echo chambers. But as researcher C. Thi Nguyen points out, a foundation of basic trust goes a surprisingly long way in getting people to question entrenched ideas. One reason echo chambers are so tough to penetrate is that members systematically mistrust outside information, as Rush Limbaugh trained listeners to do when he derided the “mainstream media.” As a result, simply exposing those in the echo chamber to different views won’t work — they’ll just write those views off as suspect. A better tactic is to establish rapport with people before offering new or opposing opinions. “Since echo chambers work by building distrust towards outside members,” writes Nguyen, a University of Utah philosopher, “the route to unmaking them should involve cultivating trust between echo chamber members and outsiders.” In this sense, Boardman has a leg up as a fixture of his community. He does have occasional critics, of course. “I’ve got a couple people who are arguing with me online, and I’ve got one really impressive hate mail,” he says. But so far, he’s gotten more positive comments than negative ones, and he thinks that’s partly due to the trust he’s earned as a local doctor. “People know who I am, and they know people who know me. I’m not just a carpetbagger from Madison.” Boardman’s months-long test run is going well enough that people now contact him hoping to replicate it. Wisconsin donors are now buying ad space for the “Barn Owl” in a nearby Buffalo County publication, and one reader in rural Oregon wants to publish Boardman’s columns in his own local paper. No matter what happens with these offshoots — or with other columns the “Barn Owl” may inspire — Boardman plans to keep writing each week, connecting with steady readers who rely on his perspective. “Part of the point is just, you continue to be present, right?” he says. “You are an opinion that remains there and it doesn’t drift away.”