Copyright Vulture

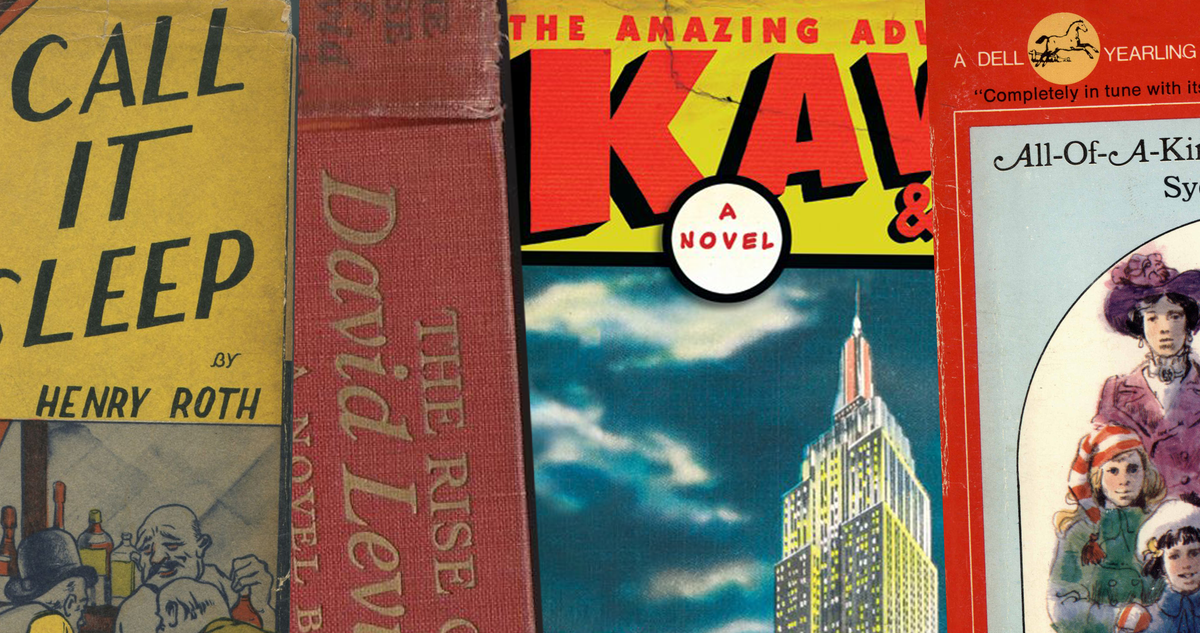

The plot of every Jewish holiday goes something like this: They tried to kill us, we survived, let’s eat. On Purim, we revel in the tale of a Persian court adviser who tries and fails to exterminate the Jews. We skip the part where, after he is hanged, those same Jews kill 75,000 Persians as a form of preemptive self-defense. At Seder, we make a meal out of being slaves in Egypt; Hagar, the Egyptian slave owned by Abraham and Sarah, tends to go unmentioned. These details didn’t make it into my religious education. They would have complicated the larger narrative that many Jews tell ourselves and others about who we are: a powerless, morally infallible minority struggling to stay alive in a world that wants us dead. I understand the appeal of this story. Telling it keeps us tethered to our past, which all too often has been a history of persecution. As Peter Beinart points out in his recent book, Being Jewish After the Destruction of Gaza, “there are still fewer Jews alive today than there were in 1939. It’s not surprising, then, that victim often feels like our natural role.” And it’s not just history: The past year has seen deadly attacks against Jews in Washington, D.C., and Boulder, Colorado. To some, Hamas’ massacre on October 7 was proof that the story is as relevant now as ever. Israel’s genocidal campaign in Gaza has laid bare the plot holes in this story. One especially glaring inconsistency is that while we are a small minority, and though we are persecuted in many quarters, we are not powerless. In fact, Jews in the United States and Israel wield a great deal of power — economically, politically, and militarily. According to a Pew survey conducted in 2020, about half of American Jews report their income as being at least $100,000, “much higher than the percentage of all U.S. households at that level.” From 2010 to 2020, a third of Supreme Court justices were Jewish, though Jews make up less than 3 percent of the U.S. population. Israel is a wealthy country with a robust military widely believed to have nuclear weapons. That country has killed at least 66,000 Palestinians since October 7, around half of whom were women and children. So much for moral infallibility. But Jewish power is often mere subtext to our story. Acknowledging it can feel like giving fuel to antisemites, who see in those statistics evidence of a vast con spiracy. That’s not the only reason we struggle to accept our power. It also scrambles our collective sense of self and forces us to take responsibility for what has been done in our name. “It evokes something unnerving,” Beinart writes, “something our tradition knows: that Jews can be Pharaohs too.” But where in our tradition? I’m not a student of the Torah, but I am a novelist, and for the past hundred years, the novel, not the Torah or the Talmud, has been the medium through which many American Jews work through questions of identity and morality. And so I sifted through a century of stories in the hope of understanding how Jewish writers in America have addressed their ever-changing relationship to power. One doesn’t need to have read Henry Roth’s opus Call It Sleep to know the narrative tropes of the Jewish American immigrant experience. They were illustrated in Sydney Taylor’s children’s series, All-of-a-Kind Family, and committed to celluloid in films like Once Upon a Time in America and, more recently, The Brutalist. Growing up in the ’90s, I first encountered many of them second-hand, as in the Simpsons episode in which Krusty the Clown is revealed to be Herschel Krustofsky, a rabbi’s son who grew up on the Lower East Side of Springfield. These stories all deal in one way or another with the challenges of the Jewish immigrant, in particular poverty and marginalization. So I was surprised to discover, in my late 20s, a body of early Jewish American fiction that deals with a seemingly opposed set of problems: those of assimilation and success. In fact, the first major Jewish American novel, 1917’s The Rise of David Levinsky, by Abraham Cahan, reads like Ragged Dick on downers: The eponymous hero pulls himself out of poverty only to end up wealthy but alone, trapped in a life “devoid of significance.” As it turned out, Jewish American writers have been worrying about the cost of power since the first great wave of immigration brought millions of Eastern European Jews to these shores. A similar trajectory — rags to riches to regret — haunts the fiction of Anzia Yezierska, the other major Jewish American writer in the decades before Call It Sleep. Like many Jewish immigrants of her generation, Yezierska fled the Russian empire and landed on the Lower East Side, where she worked in sweatshops, restaurants, and laundries. Her first story to achieve recognition, “The Fat of the Land” from 1919, is a cautionary tale of upward mobility, a theme she would return to throughout her career. When we first meet Hanneh Breineh, the protagonist, she is half-mad with hunger and struggling to feed her six children. All the hallmarks of Jewish immigrant fiction can be found in the story’s first pages: the cramped tenement, the stale bread, the pushcarts. “Without money,” she tells her neighbor, Mrs. Pelz, “I’m a living dead one.” Years later, one of Hanneh’s sons finds success in the garment business and moves his mother uptown. On Riverside Drive, Hanneh can’t relate to her new neighbors. Her spoiled children criticize her immigrant manners. She feels “cut off from air, from life, from everything warm and human,” her material comforts having “choked and crushed the life within her.” Fed up with her luxe accommodations, Hanneh eventually returns to Delancey Street to stay with Mrs. Pelz. When she arrives, however, she finds she can’t tolerate the cold, the mice, the soiled mattress. She may not feel at home in her new life, but she isn’t home in her old one, either. The story ends with Hanneh standing in the rain outside her Riverside Drive apartment, “unable to enter, and yet knowing full well that she would have to enter.” Other characters in Yezierska’s fiction meet a similar fate upon getting a taste of the good life. Some essential part of them is always left behind. It’s no surprise that writers like Cahan and Yezierska cautioned against extravagant material wealth; like many Lower East Side Jews, they were socialists. But the story is not simply about politics. After publishing her first collection — a year after “The Fat of the Land” — Yezierska received a telegram from a Hollywood agent asking her to “ telephone immediately.” Too poor to call the movie studio, she pawned her mother’s Sabbath shawl for a quarter, which she fed into a pay phone. When she reached the agent, she learned Samuel Goldwyn wanted to buy the film rights to her book for $10,000. In the press, Yezierska soon became known as the “Sweatshop Cinderella,” spirited away from Hester Street to Hollywood by limousine. The fairy tale came to a fittingly Yezierskan end. She later wrote that her success left her feeling “like the beggar who drowned in a barrel of cream,” cut off from the people and the poverty that had been her creative inspiration. Within a decade, she had vanished into obscurity. (A critic accused her of exhausting the one story she had to tell.) In an article for Cosmopolitan called “This Is What $10,000 Did to Me,” she wrote that she had lost her soul. After World War II, anxieties about assimilation inspired an increasingly morally complex literature. Writers like Philip Roth, Saul Bellow, Grace Paley, Norman Mailer, Cynthia Ozick, and Bernard Malamud trained their considerable energies on questions of identity, exploring what it meant to hold dual loyalties to a democratic ideal and to one’s own tribe. Unlike Yezierska, these writers were born and raised in America (or Canada, in Bellow’s case) and wrote in the American Century. Native English speakers with public educations, they mostly occupied a higher social status than their parents, from whom they inherited what the critic Irving Howe called “an ironic relationship to power.” To Howe, this was their “cultural legacy.” Roth probed that relationship in his breakout 1959 short story, “Defender of the Faith.” Its subject is Sheldon Grossbart, a military trainee who exploits his Judaism for personal gain. He gets out of barracks cleanings by claiming he has to go to shul. He demands special meals despite not keeping kosher. Yet no matter how much Grossbart bothers his super visor, Sergeant Nathan Marx, the sergeant finds himself defending his trainee. If Grossbart represents a certain kind of Jewish figure — powerless but clever, surviving by his wits — Marx represents another and, at the time, newer type: the half-assimilated company man, torn between tribal solidarity and his duties to the dominant culture (in this case, the U.S. military) that has granted him a measure of conditional power. Like Roth, who insisted he was not an “American Jewish writer” but an American writer, Marx’s loyalty is to his country — but all it takes is a Yiddish term of endearment to undo him. “‘Leben!’” he thinks, when he hears Grossbart use the word. “My grandmother’s word for me!” Toward the end, Grossbart goes over Marx’s head and pulls some strings to get himself out of combat duty. Marx retaliates by pulling a string of his own, getting Grossbart back on the list of soldiers headed to the Pacific, potentially turning his co-religionist into cannon fodder. This is not a decision he makes lightly: The story ends with Marx “ resisting with all my will an impulse to turn and seek pardon for my vindictiveness.” But he does resist and takes responsibility for what he’s done. When “Defender” was published in The New Yorker, it caused an uproar. Establishment Jews felt Roth had painted them in a poor light. The problem was Grossbart, whose conniving seemed to corroborate the worst stereotypes about the Jewish people — and so soon after the Shoah. Today, as debates rage on about whether Israel can be both a Jewish state and a true democracy — for Beinart, the answer is “no” — it’s Sergeant Marx who seems more likely to offend hard-line Jewish Zionists, prioritizing democratic principles over tribal affinities. Such decisions aren’t easy, Roth suggests, especially when a third of the tribe in question has just been wiped off the face of the earth. Still, even those with limited access to power have a responsibility to their principles. In 2016, I was excited to learn that Jonathan Safran Foer’s new novel, Here I Am, his first in 11 years, would be set entirely in the present day. I had grown up reading Foer in the aughts, a decade that saw a resurgence in Jewish American fiction. A 2009 essay in Vanity Fair, “Rise of the New Yiddishists,” by David Sax, cited such figures as Nathan Englander, Michael Chabon, Dara Horn, Nicole Krauss, and Foer as redefining what it meant to be a Jewish American writer, seeking inspiration in Jewish history, folk tales, and mysticism. Theirs were best -selling, prizewinning books much discussed in Jewish families like mine. As Sax pointed out, the New Yiddishists “emerged during a turning point for American Jewish identity. Never in history have Jews been so integrated and accepted into the mainstream of a Diaspora country.” This acceptance allowed them to plumb the past and write “unabashedly, unambiguous[ly]” Jewish stories. Just as notable was what they didn’t write as much about: their own lives as American Jews in the new millen nium. In The Nation, William Deresiewicz wrote that they “appear to be avoiding their own experience because their own experience just seems too boring.” Instead of engaging with the meaning of this new sense of security, which was likely to be temporary and conditional anyway, this new generation of Jewish writers sought inspiration in past historical traumas — the Civil War (All Other Nights), the Dirty War (The Ministry of Special Cases), World War II and the Holocaust ( Everything Is Illuminated, The History of Love, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay) — or, in the case of Here I Am, imagined ones. Here I Am is the story of a family in Washington, D.C., and much of the novel is concerned with the domestic: a sick dog, a funeral, a divorce. In other words, the stuff of much contemporary fiction, albeit from a Jewish perspective, featuring Jewish characters with uniquely Jewish preoccupations: a boy’s bar mitzvah speech, the state of Steven Spielberg’s foreskin. Two hundred and fifty pages into the novel, however, an unlikely earthquake leads to a war between Israel and an unlikelier “ Transarabian” alliance. (The earthquake is a convenient way to get a war going without getting bogged down in questions of accountability.) Although dozens of pages are devoted to the war, it remains in the background, rendered as a series of headlines and news interviews. This is undoubtedly part of Foer’s broader point about the safety of being Jewish in America, the danger of being Jewish in the Middle East, and the distance — spiritual as well as geographic — between these states of being. But as I read the back half of the novel, I started to suspect that Foer didn’t trust that his readers would be moved by the mundane lives of his characters and so contrived a disaster to hang them on. Jacob, the protagonist, is constantly bemoaning his small problems, “small thoughts,” and “small feelings.” Of course, there is nothing small about a divorce or the death of a loved one; everyday domestic affairs animate many, if not most, major works of literary fiction. But reading Here I Am, I found they did feel small, largely because Jacob keeps fretting that they are. Unlike his Israeli cousin’s, his life is not in danger. Unlike his grandfather, he is not a Holocaust survivor. Assimilation and security have robbed him of the sense that his life is meaningful, urgent, and important. This might have been fruitful terrain for Foer had he not so plainly shared his character’s concerns. Rather than explore what it means to be a Jew in a time and place where, for once, we aren’t staring down extinction, Foer felt the need to raise the stakes — as though there could be no Jewish story without widespread suffering. His previous novels, both best sellers, centered on world-historical tragedies: the Holocaust, the bombing of Dresden, 9/11. Lacking a contemporary tragedy for Here I Am, Foer seemed forced to invent one, inadvertently revealing the crisis at the heart of Jewish American identity. These are strange times to be an American Jew. Antisemitic hate crimes are on the rise; at the same time, antisemitism has been weaponized by the Trump administration — and by mainstream Jewish American organizations — to quash dissent. We find ourselves in the uncomfortable position of straddling vulnerability and complicity. The contem porary Jewish American novel that may best capture this moment is Joshua Cohen’s Moving Kings. Published in 2017, the book has become newly relevant for its portrayal of the 2014 Gaza War — and the war’s impact on Americans. The first of the novel’s three sections follows David King, an outer-borough outsider at a fancy party prowling for customers and political connections. He runs his own moving-and-storage company, and his politics are “aspirational, inferior.” Like a 21st-century Sergeant Marx, he’s stuck between stations. Like many Jews of his generation, he doesn’t see himself as white, much less a gentrifier: “His color was Jewish.” His arguments with his daughter about Israel will be familiar to any Jewish person. The second section belongs to David’s Israeli cousin, Yoav, and his army friend, Uri. As soldiers, they have the power to terrorize Palestinians by destroying their homes — a power they exercise out of boredom or for no reason at all. As ex-soldiers, however, they are lost, traumatized by what they’ve seen and done and hated everywhere they go for being Jews, or Israelis, or (in ironic cases of mistaken identity) Arabs. Cohen excels at describing the existential aimlessness afflicting young men set loose upon the world after completing their compulsory military service. Many of them surf and pay for sex while backpacking through Southeast Asia. Yoav and Uri wind up working for David. The third section introduces another main character, Avery Luter, a.k.a. Imamu Nabi, a Vietnam veteran facing eviction. The job falls to Yoav and Uri. The premise of the novel lies in the parallels between the Israeli occupation and the eviction of a Black Muslim from his home by Jewish American and Israeli movers: “They were still going into a house and checking the rooms by the floor. Checking for people, checking for possessions. Clearing the people before clearing the possessions. The possessions would stay with them, the people were allowed to go wherever, provided it was always on the other side of the propertyline.” Moving Kings is the rare contem porary novel to grapple with the paradox of power and persecution that defines Jewish life in the U.S. today. Whether American Jews want this is another story. Moving Kings was released to mixed reviews: celebrated in the Washington Post, panned in the New York Times. Cohen’s next novel, The Netanyahus, was set in the 1950s and focuses on the only Jewish professor at a fictional college, a man on the receiving end of much antisemitism. The novel not only won the Pulitzer Prize, it won a National Jewish Book Award. Given the differences in reception between these two books — one set in the present in which Jews are persecuting people and one set in a past defined by the persecution of the Jews — it seems clear which dynamic many of us would prefer to linger on. It’s still too soon for novels written and set after October 7, but some stories have begun to trickle out. Cohen’s “My Camp,” published last year in The New Yorker, follows a writer who protests the war by raising money on behalf of the IDF and sending it to charities for Gaza — but not before buying himself a place in the Pine Barrens. A slew of new nonfiction books explores similar terrain. The British writer Rachel Cockerell’s Melting Point, published earlier this year in the U.S., is a formally inventive history of the early days of Zionism. Pulitzer Prize winner Benjamin Moser is also working on a history of Zionism, as told from the perspective of Jews around the world who resisted it, called Anti-Zionism: A Jewish History. Times reporter Marc Tracy is writing a history of (and present report on) the Jewish Diaspora with the working title Far-Flung. Then there’s Beinart. “From the destruction of the Second Temple to the expulsion from Spain to the Holocaust,” he writes in Being Jewish After the Destruction of Gaza, “Jews have told new stories to answer the horrors we endured. We must now tell a new story to answer the horror that a Jewish country has perpetrated, with the support of many Jews around the world.” The challenge facing Jewish fiction writers today is in telling that story or stories like it — stories in which Jews behave badly in the name of Judaism — without fear that our work will be used against us or co-opted to nefarious ends. Then again, that’s practically an occupational hazard. Countless Jewish American writers have been accused of sketching unflattering portraits of their people; the Zionist activist Eliahu Ben-Horin called “Defender of the Faith” an “ugly piece of antisemitic literature.” But literature is not public relations and, in any case, cannot be written from a place of fear. Defending “Defender” in 1963, Roth cautioned against allowing antisemites, or non-Jews generally, to control the conversation. “This is not fighting antisemitism,” he wrote, “but submitting to it.”