By Alex Pappademas

Copyright gq

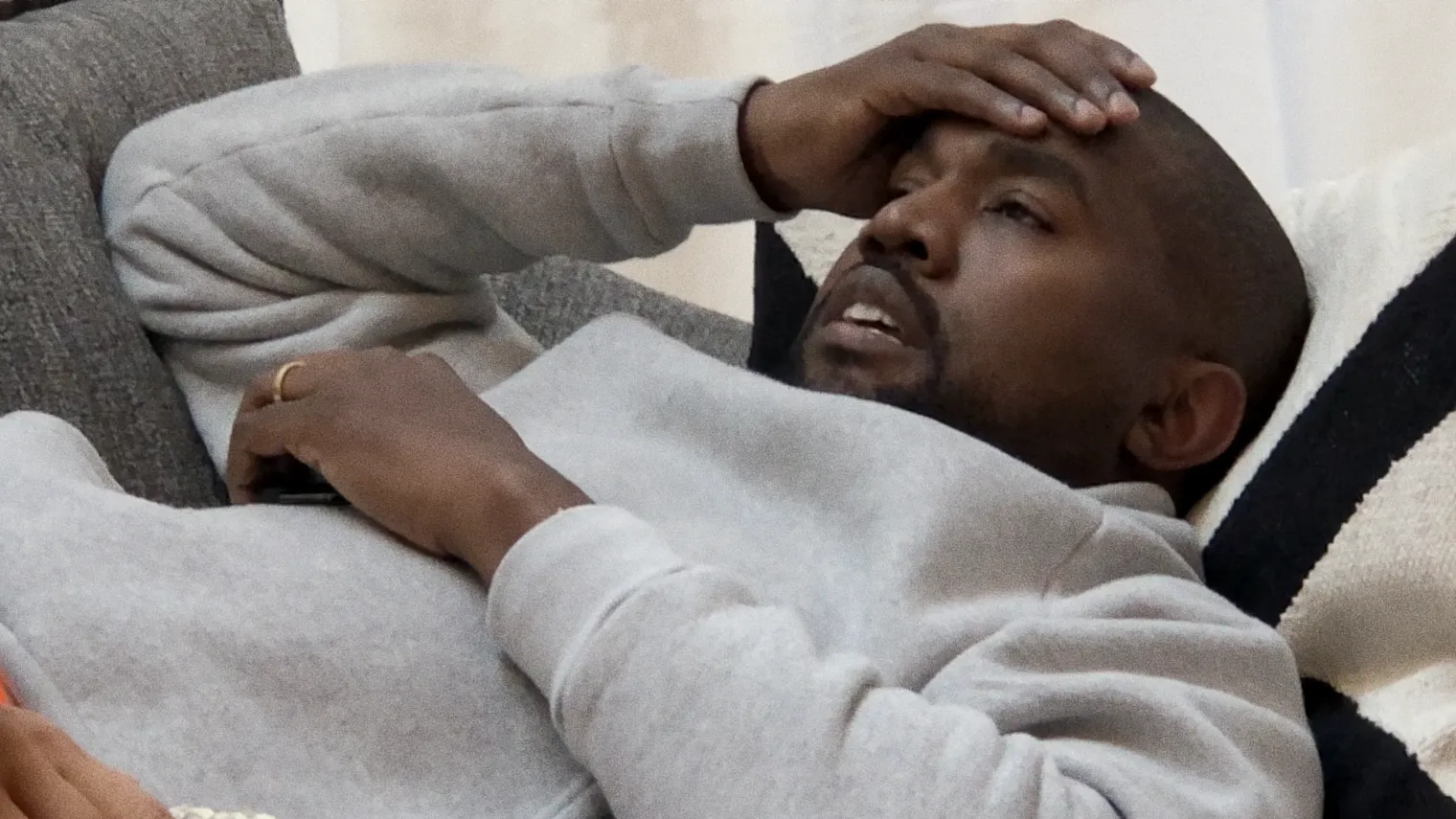

In Whose Name, a sleek and ominous and sometimes uncomfortably intimate documentary about Kanye West by director Nico Ballesteros, offers a verité-ish look at some particularly-tumultuous years in the never-not-tumultuous life of the producer-turned-rapper-turned cultural flashpoint who now goes by “Ye.” The first time I watched it, I felt like my own history with Kanye was flashing before my eyes, and sat there in the dark filling 26 notebook pages with thoughts and theories. The second time I watched it, I just got depressed, and drove home in radio silence.

Please interpret all that as a thumbs-up review: If Ye has ever meant something to you, whether you’ve since had it up to here with his bullshit or somehow still can’t get enough of said bullshit, you should absolutely see this film while you can. It’s still playing in limited release across the country, and may have pulled in enough money in its first and second weekend to stick around a bit longer—although it’s likely to get knocked out of the cultural conversation (and off more than a few multiplex screens) when Taylor Swift’s The Official Release Party of a Showgirl opens theatrically on Friday. Yes, at least zeitgeist-wise, Taylor is about to interrupt Kanye; if you’re a student of history and/or an afficionado of fridge-temp revenge, I probably don’t have to explain what’s both funny and poetic about that.

The first time Nico Ballesteros pointed a camera at Kanye West, it was 2018, and West was standing outside an office building in Calabasas, eating a taco from Taco Bell off the rear trunk lid of his Maybach. Ballesteros was only 18 at the time, an aspiring filmmaker from Orange County. He was still in high school, but through studious social-media networking and a few lucky breaks he’d worked his way to the outer edge of Ye’s inner circle. He’d become known to the team at Ye’s Calabasas office—the headquarters of Yeezy, Ye’s fashion brand, but also a more general-purpose creative hub that Ye called “the Energy Center”—as a videographer, and before long he got the call that changed everything. The indie-rock group Francis and the Lights, one of Ye’s favorite bands around that time, were doing a private show at the Yeezy offices, and Ye’s team needed someone to document the event.

They told him to come to the office the next day. They told him to bring a night-vision camera. “They were like, ‘Kanye just wants you to film,’” Ballesteros recalls. “‘Just don’t stop filming. The moment you find him, just follow him. Don’t stop until somebody says stop.’”

So Ballesteros sourced two camcorders with night-vision capability off Craigslist. And the next day, he drove to Calabasas. He’d never been there before. The sun was setting over the rolling hills as he arrived. “It’s, like, this mystical place,” he says. The Yeezy office was a mystical place, too, but one that Ballesteros was more familiar with. He’d spent years observing Ye through the keyhole of social media; he’d seen a million pictures of Ye walking out of this very building.

“There was so much aura with this office,” he says. “For me to now go there—it was the Charlie and the Chocolate Factory moment.”

And not long after Ballesteros got there, so did Ye. Ballesteros found him outside, standing with the director and photographer Eli Russell Linnetz, and started shooting. Nobody said stop. “He just didn’t acknowledge my presence—in a good way,” Ballesteros says. “He was just enjoying his taco, talking to Eli.”

Ye’s then-wife Kim Kardashian arrived. The concert started. Ballesteros moved through the crowd with his night-vision camera, filming Ye while also taking note of the ecosystem of the room. Creative directors and wannabe creative directors and designers and online demi-celebs. How they interacted with each other, how they spoke, how they navigated the gravitational fields of power in that room.

Then there was a commotion. Ballesteros saw Ye getting excited. “I whip-pan,” he remembers, “and Elon Musk comes in. And I’m like, ‘Wait a minute. Whoa. This is really interesting.’”

The next day, Ballesteros got another call from the team in Calabasas. Ye wanted him to start coming out to the office every day, to film the meetings he was taking there. Ballesteros’ first thought was about how that would work logistically; the drive from Orange County to Calabasas at rush hour takes ninety minutes on the best of days. But he wasn’t about to say “No.”

For the next six years, wherever Ye went, Ballesteros went with him, filming him more or less continuously, usually with a handheld iPhone. In Whose Name, culled from nearly 3,000 hours of footage Ballesteros collected during that six-year period, is in theaters now. It’s a bleak yet fascinating work of art wholly unlike the authorized, myth-burnishing docu-mercials cluttering up the “Music Documentaries” tab on Netflix or Hulu.

There are no talking-head interviews, no narration, and—aside from title cards dividing the story into three acts, like the episodes of a Greek tragedy—no onscreen text to tell us what we’re looking at and why. It doesn’t hold our hands and lead us to a conclusion; it doesn’t attempt to explain Ye’s decisions, or justify them, or condemn them. It just says, Here’s what it was like—what it was like to be Ye, during one of the most chaotic and difficult periods of his rarely-undifficult life, and (by implication) what it was like to be Ballesteros, an iPhone-toting fly on Ye’s wall.

Those Netflix/Hulu docs are artistically middling in part because they’re usually produced with the cooperation of their subjects, by filmmakers willing to barter away some measure of creative control in exchange for access, music rights, and everything else a documentary filmmaker can’t go without. Ballesteros, by contrast, had Ye’s cooperation, and seemingly-unfettered access to his creative, professional and personal life, but collected all this footage without ever making any kind of formal arrangement with Ye about what he might do with it afterwards; he even used his own credit card to buy the various iPhones he used to shoot it.

He and Ye did talk about what they wanted the movie to be. In the beginning, Ye imagined they were making a film about mental health (and in a sense, given that almost everything that happens in the movie could arguably be categorized as a downstream result of Ye’s decision to stop taking psychiatric medication, they sort of have). But he wasn’t involved creatively in the finished product. (He has, though, seen the movie three times, in various stages of completion; Ballesteros says he called the final product “crisp,” which was high praise, and gave the movie his full locked-in attention each time he watched it, which one imagines is even higher praise.)

In Whose Name is a more-or-less authorized film that feels like an unauthorized one, something fans might pass around as a Vimeo link, even against their hero’s wishes. Instead, it’s screening in 1,000 theaters across the country—although this almost didn’t happen. Nick Jarjour, Ballesteros’ manager, tells me that in the wake of Ye’s anti-Semitic heel-turn circa 2022, one early distribution deal was yanked off the table almost immediately, and that convincing anyone to even watch the film, let alone distribute it, got significantly harder after that.

“Somehow it felt like the negativity surrounding Ye had been transferred onto Nico,” Jarjour says. “Every chairman, every streamer, everybody had slammed the door shut.” (Unusually for a high-profile documentary feature, In Whose Name was not screened at even one major film festival; one person familiar with the situation suggests that programmers passed on it out of fear that Ye himself would show up.)

Eventually, though, Jarjour says, he screened the film for Gee Roberson, a film producer and veteran artist manager who’d actually managed Kanye decades earlier and had brokered his deal with Roc-a-Fella Records. Roberson had liked it enough to introduce Jarjour to a “very discreet and powerful operator” within the entertainment industry. And that operator connected them with Simran Singh, a powerful music-business attorney who was also blown away by Nico’s footage. “You don’t get that type of access,” Singh tells me on a Zoom call. “Even documentaries I’ve been part of—they are highly influenced by what the artists involved want to portray, for a lot of reasons. Studios, I think, are afraid of that backlash.”

They decided to distribute it independently; Singh flew around the country screening the movie for exhibitors like Cinemark and AMC. “Essentially, we built out a full-fledged theatrical distribution company, just for this film,” Singh says. (When it’s suggested that this is similar to the way Taylor Swift brought out her Eras Tour film, partnering directly with AMC in an end run around the studios, Singh says yes, it is, but points out: “She could have gone anywhere she wanted, anywhere in the world—any company would have taken her,” which was clearly not the case here.) Singh also went on to put millions of dollars of his own money into a marketing campaign for the movie. He is, he says, “heavily invested” in the project, in all senses. “I don’t know if my publicist would advise me to tell people that,” he says, “but, yeah. I do crazy things, man. I do crazy things.”

When I talk to Singh and Jarjour about the movie they both say they fought for it because they believe in Ballesteros, and the film, and what they think it has to say about mental health—namely, that mental-health struggles can take anyone down, even one of the most famous people in America. In the sense that In Whose Name, broadly speaking, serves as a case study of what can happen to someone who stops taking a prescribed psychiatric medication they believe is dimming their natural creativity, a mental-health documentary is exactly what it is. Whether it’s a particularly useful case study is another question; the circumstances it depicts are pretty specific to exactly one person’s extremely rarefied experience.

Keith Richards once said, after one of his many run-ins with the authorities, that what he had was not a drug problem but a police problem. Ye’s issue, during the era depicted in this movie, is seemingly less that he’s bipolar and has chosen to forego medication and more that he’s bipolar and has chosen to forego medication and someone is constantly putting him in front of a microphone or a camera and broadcasting whatever he says to the entire world, including the publicly-traded companies that are his partners and are then obligated to take action. In some ways, as a rich guy with a catalog of hit records and an influential fashion brand, Ye is more shielded from direct consequences than a more average off-their-meds American, but he also had far more to lose.

Just over a week before In Whose Name opens in theaters, I meet Ballesteros at a post-production facility near Santa Monica Boulevard in Hollywood, to talk about the movie and the years he gave over to making it, and the logistical and psychological effort it took to winnow those 3,000 hours down to the length of a commercially-releasable feature film. (Ballesteros always saw it as a feature, rather than, say, a limited series. The finished version clocks in at a compact 106 minutes; one early cut ran two hours and 40 minutes, before a friend gently told Nico that audiences would probably balk at the idea of sitting through an almost-three-hour documentary, complete with intermission, about anybody, even Kanye West.)

Ballesteros is slim and tall and polite and serious, with a sparse mustache and longish dark hair that makes him look a bit like a young Nick Cave. Today, though, he’s dressed like a young Nick Cave on his way to teach grad-school English in the Texas hill country—silver-tipped belt, reptile cowboy boots, woven summer sport coat.

He’s 26, and this is maybe the second or third interview he’s done about the movie that’s consumed his life for seven years. He’s articulate and focused, a complete-thoughts-in-complete sentences type of speaker, but sometimes he gets lost in context, in recounting every single event that led up to some turning point or other, and it takes us forty-five minutes, in conversation, to get to the part of the story where he films Ye eating that taco. At one point he tells me that the story of Jack Kerouac’s “infinite scroll” version of On the Road—the first draft of the book, which Kerouac typed in its entirety on a single 120-foot sheet of paper—influenced his approach to the editing of In Whose Name, a process that at one point involved nine thousand individual strips of paper, each one representing ten to maybe sixty seconds of the film, taped to the walls of an Airbnb in Palm Springs.

The day after we have this conversation, he calls me on the phone, and I start to worry that he’s going to ask me to strike some sensitive detail from the record. But it turns out he just wants to fill me in on a trip he took to Paris while making the film, where he met Tony Shafrazi, who’d been Basquiat and Keith Haring’s art dealer once upon a time, and he wants to tell me this because he thinks I should know it was Shafrazi who urged him to read Kerouac. Everything is connected, everything is pivotal; it’s not hard to understand how the movie itself became a bit of an infinite scroll, at least for a while.

Ballesteros first picked up a video camera when he was about eight years old. He started filming his day-to-day life, the way another kind of kid might keep a journal. But the important part was what happened at the end of the day, when he’d run back what he’d shot.

“I would play the day back on the TV,” he says. “I would relive my day, and try to understand the phenomenology of a lived experience captured and then replayed, and how that feels.”

Later he’d learn about the psychological phenomenon in which people viewing images in sequence ascribe different emotions to the same picture of a human face depending on what it’s juxtaposed with. This is called the Kuleshov Effect, although of course eight-year-old Ballesteros didn’t know that. He just knew that when he’d hook the camera up to the TV and play his day back on a screen, even things that had happened a few hours earlier seemed to take on a different meaning.

He went to Orange County School of the Arts, a public arts charter school in Santa Ana, centrally located between his mother’s house in Fullerton and his father’s house in Mission Viejo. By the time he got there he knew he wanted to make films. But he wasn’t thinking about making the next Star Wars or becoming his generation’s Spielberg. He was interested in the technical side of filmmaking—by the time he was a sophomore, he was working as a DP on other students’ senior-project films—but he didn’t really watch a lot of movies. He watched YouTube, early vloggers like Casey Neistat, and Vice’s gonzo news shows. A documentary-film class lit his brain up. He started to think about nonfiction filmmaking as a space in which he could thrive.

Back then he still wore regular jeans and button-down shirts, like any other high schooler. Fashion, to him, was something remote—the word made him think of The Devil Wears Prada. But then he started making friends with kids at his school for whom fashion was a subcultural identity with a language and value system all its own—kids who wore Supreme and (yes) Yeezys, and spoke with reverence of “Rick” and “Raf” and “the Antwerp Six.” These kids got Ballesteros interested in hip-hop, streetwear, skateboarding, high fashion, and Japanese style, and the designers and other creatives whose work lived at the intersection of those things, including Virgil Abloh (then the creative director of Ye’s mystery-shrouded creative agency DONDA) and Ye himself.

Those kids took Ballesteros to see Travis Scott kick off his Rodeo Tour at the Observatory in Santa Ana. And one day in early 2016 they all ditched school to sit in a theater and watch a live stream of Ye unveiling two new projects—his third Yeezy collection for Adidas, and his seventh studio album The Life of Pablo—at Madison Square Garden.

It was a pinnacle moment in Ye’s history, a massive crossover event uniting celebrity and subculture, attended by a galaxy of stars. The Kardashians in furs and custom Balmain; everyone from Naomi Campbell to Lil Yachty modeling Ye’s post-apocalyptic athleisure; Travis Scott and A$AP Rocky jumping around like contest winners behind Ye, the man of the hour, as he worked the aux cord in a dad hat and a red I FEEL LIKE PABLO sweatshirt, busting with pride as he premiered what’s still maybe the best music he’s ever made, from gospel-infused instant classics like “Ultralight Beam” and the infamous Taylor Swift-baiting “Famous.”

In that moment, on a weekday in February, sitting in an AMC multiplex in Santa Ana watching Ye’s moment of triumph, Ballesteros knew what he wanted to do with his life. He wanted to make a documentary about Ye and the cultural zeitgeist, and how those two forces shaped each other. He’d entered high school intending to go on to USC film school after he graduated; by senior year, the whole idea of college had fallen off his radar. “All my friends are going to NYU,” he remembers. “Some are going to Harvard. Everybody’s going to great schools. And I’m the kid who’s like, No. I’m going to go make a documentary with Kanye.”

By then Ballesteros had started making connections with Instagram tastemakers who moved in Ye’s orbit—people like the content creator Kerwin Frost and then-teenage model Luka Sabbat and Instagram fit-pic kingpins known by handles like “Mike the Ruler” and “Asspizza.”

In those days, Ballesteros says, it was easier to build a network through friends of friends. “Social media changed,” he says, “because of TikTok. The algorithm now is an intention map, where it just puts everything out at the same level, and anything that gains certain traction can pick up in the algorithm. But back then, it was a social map. So it mattered who followed you, who you followed, who liked your photo. That’s what the algorithm was based around. That was clout culture.”

He volunteered to shoot a launch event for a collaboration between Frost’s crew, Spaghetti Boys, and Abloh’s brand Off-White. “I take the photos, the photos go up. Boom—now Virgil’s liking the photos. I’m like, Oh, OK—this is organically happening,” he says.

After that, things moved fast; the degrees of separation between him and Ye began collapsing. “I’m in class, I’m texting people, and they’re like, We’re with Kanye in Malibu. Link up later?”

But a number of other things happened before Ballesteros actually met Ye. In October 2016, Ye cut short a show in New York City after learning that Kim Kardashian had been held at gunpoint and robbed in a Paris hotel suite. On November 8, Donald Trump was elected President of the United States. In November, after resuming his Saint Pablo Tour, Ye delivered a 25-minute monologue during a show in San Diego, announcing that if he’d voted that year, it would have been for Trump. On November 21st, Ye announced that he was cancelling the remaining dates of the tour due to exhaustion and stress.

That same day, Ye’s trainer Harley Pasternak visited Ye at his home in Los Angeles. Later, in a deposition quoted by The New York Times, Pasternak would say he’d found Ye “writing Bible verses and drawing spaceships on bedsheets with a Sharpie.” A doctor called 911, and Ye was placed on involuntary psych hold at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center for nine days. So began a new and strange chapter in Ye’s life and career. In 2017, he revealed that he’d been diagnosed with bipolar disorder during his hospital stay. The following year, he began telling interviewers that he’d stopped taking the psychiatric medications he’d been prescribed, believing that the meds were blunting his creativity.

Ballesteros says Ye’s hospitalization “was when everything changed.” He realized, he says, that the film he wanted to make about Ye would have to be about more than just the cultural union of hip-hop and high fashion: “It’s about something much greater. It’s about the psychology of an artist, and chasing ideas, the consequences of that.”

He started reading Freud and Jung, wrestling with big ideas. He was 18 by then; he was, he says, “dealing with a lot of angst, just trying to find myself…I wanted to get out of high school so bad. My senior year was just horrible. I hated being in class. All I wanted was to be with my new friends out in LA or New York, or wherever they were.”

So when he got the call about the Francis and the Lights show, he didn’t hesitate. And when they asked him to come back, he came back. He’d wake up in Orange County in the same bed he’d slept in as a kid, push through traffic on the 5 and the 101, and get to Calabasas in time to film Ye meeting with the director Steve McQueen, or The Weeknd, or Spike Jonze, or NFL great Jim Brown, or Drake.

What he didn’t do, at least at first, was talk—not to Ye, anyway, not for a while. There’s footage of the Drake meeting in In Whose Name; we see Ye introduce Drake to Ballesteros. “That was the first day Ye talked to him,” Nick Jarjour says. “He had already been there for months, literally. Like Silent Bob.”

When asked what it was that led Ye to trust him with this much access to the inner workings of the Energy Center on the basis of very little, Ballesteros answers, “Youth.” There were a lot of young people in Ye’s orbit around that time. Jarjour calls them the “culture kids”—would-be artists, would-be designers, would-be documentarians, all looking to trade ideas and intel for clout.

“These baby Virgils and baby Stanley Kubricks,” Jarjour says, “all hanging out together.”

But Ballesteros, Jarjour says, “wasn’t like the other culture kids, who would demand their place, their credit, their name, who would try to outshine the master…Everybody is constantly selling themselves, trying to do this, trying to do that. [Ballesteros] didn’t require any of that validation from Ye or any of those people around, which made him—this is a Hollywood thing to say, but it’s like it made him already a star.”

Within a few months of Ballesteros’ arrival on the scene, Jarjour says, “Ye cut everybody else out. He’s like, ‘It’s all about Nico.’”

At first it was a nine-to-five job, although nine-to-five sometimes meant nine-to-six, or nine-to-7. But before long, Ballesteros found himself in Wyoming, filming at the sessions for Ye’s collaborative album with Kid Cudi, Kids See Ghosts. After that, Ye took a vacation, and Ballesteros took a vacation, but when he got back to California he got word that Ye had a lot of travel coming up and wanted Ballesteros with him.

After that, Ballesteros says, he and his subject started “just jet-setting all over the place.” They went to New York, for a party celebrating the 50th anniversary of Ralph Lauren, and then to Chicago, where they moved into the Waldorf-Astoria for a while. Ballesteros would get up in the morning, walk down a hallway lined with Kanye’s security guards, and knock on the door of Kanye’s room. He’d be in there eating breakfast, doing business on the phone. Nico would start filming. And then, boom, Kanye would get another idea—like when he decided he wanted to work with the rapper 6ix9ine, because he wanted to work with people who’d been cancelled, and it turned out that 6ix9ine was in Colombia, so Ye and Ballesteros went to Colombia.

That was where Kanye drew a little sketch of Ballesteros, just a mouthless face with sunglasses and a fringe of hair, filming with his iPhone, and captioned it “NICO WITH THE CAMERA,” and posted it on his Instagram, and after that Ballesteros was a visible mystery man, a known satellite in Kanye’s galaxy, part of the Yeezy Extended Universe. People on Reddit and Instagram had been taking note of his presence in the background of photos, but NICO WITH THE CAMERA made him, he says. “I was like, ‘Okay, this is official. This is who I am now.’”

“He grew his own weird cult following,” Jarjour says, “that was 99% art-house creative kids. He built this little culture around him that’s really based on, You can take nothing and turn it into something. This kid with an iPhone that followed Kanye West and Kim Kardashian, the biggest celebrities in the world at that time, twenty-four hours a day.”

Twenty-four hours a day is an exaggeration, but only slightly—whenever Ye was working, Ballesteros was there filming, sometimes for eighteen hours at a time. After that he’d go back to wherever they were staying, order something off the late-night menu, shower and get to sleep by three or four o’clock in the morning, and the next day he’d be up at seven, packing bags and charging batteries while doing what he could to archive the previous day’s footage. The clips were unwieldy—sometimes he’d shoot for two hours straight, but shooting for eight hours wasn’t unheard of.

“I didn’t want to stop recording, ever,” he says, “because I felt like if I stopped, lo and behold, that would be the only moment that I missed, the most important moment ever.” It got to the point, he says, “where I just started buying more iPhones. If I filled up a phone and I didn’t have time to dump [the contents], I would just buy another phone on my credit card and keep it going.”

He wouldn’t eat when everybody else ate, because he’d be busy filming everybody else eating and couldn’t put the camera down. “Eventually,” he says, “what happened was I would do this thing where I’d prop the phone up on a glass of orange juice and eat some eggs. I did eventually do that, but in the beginning, I’m just so in it and thinking, “I got to document and I got to be present.” And I don’t want to break the fourth wall in a way or become a part of the mise en scène. I wanted the mise en scène to be untouched by me.”

Some of what he captured was banal. But only some of it, according to documentary filmmaker Justin Staple, who was one of the first editors to try cutting a movie out of Ballesteros’ footage and has an co-executive-producer credit on In Whose Name. “This is someone who wanted to creative-direct the world, to change the world, and was becoming the richest Black man in America, and all these historic things,” Staple says. “And the 3,000 hours were highly, highly watchable. Every day, all of it could have been usable, in some sense.”

Around the time Ballesteros began following him with a camera, Ye became one of the most controversial entertainers in America—or maybe one of the most controversial people, period. He’d touched the third rail of the culture before—with his off-script declaration that “George Bush doesn’t care about Black people” during a 2005 telethon for Hurricane Katrina relief, by interrupting Taylor Swift’s Grammy acceptance speech, and by tweeting “BILL COSBY INNOCENT!!!!!!!!!!” in 2016, after more than fifty women had accused the comedian of sexual misconduct.

But in December 2016, he visited Trump Tower to meet with a President-elect most of his liberal fans viewed as an ascendant supervillain. By 2018, he’d become Trump’s most visible Black supporter, tweeting approvingly about the President’s “dragon energy”; that September, he wore a MAGA hat during a performance on Saturday Night Live, then delivered an extended rant, cut from the live broadcast, about the liberal media, “monolithic thought,” and his support for the President. A month later, Ye visited the Oval Office, where he hugged the President in front of news cameras while Trump grinned his best canary-eating I-love-this-crazy-guy grin.

Chances are you remember most of this stuff; it wasn’t that long ago. Ye tweeted about, and then started palling around with, conservative commentator and onetime Turning Point USA communications director Candace Owens. Owens’ onetime boss Charlie Kirk shows up very briefly in the film, which is an odd coincidence for a movie released this month, but it’s Owens who seems to have gotten in Ye’s head early and often; it’s Owens we see in the movie diagramming for Ye, on a dry-erase board, how politics is downstream from culture. You may recall the Paris fashion show where Ye and Owens showed up in matching t-shirts that read WHITE LIVES MATTER, a provocation about on par with any other idea ever hatched, as this one appears to have been, inside the offices of the Daily Wire. And then not long after that, as if looking for a hotter stove to place his hand on than the idea that Black Lives Matter was a scam, Ye started making increasingly overt anti-Semitic comments and social-media posts, like the instantly-infamous tweet in which he announced plans to take a nap and then go “death con 3 on JEWISH PEOPLE.”

In Whose Name doesn’t answer, or attempt to answer, the bigger question that’s hung in the air throughout Ye’s years-long MAGA-morphosis—namely, whether his support for Trump (and later, his avowed anti-Semitism) was something he actually believed, or a vast lib-triggering performance piece concocted by an artist so averse to being told what to do that he felt obligated to hurl himself against the new social barricades of the so-called “woke” era, over and over, even at the cost of his career.

Whether “death con 3” was an actual heartfelt statement of hatred or a shitpost or a mentally ill man’s cry for help—and it was probably all of the above—it accelerated things precipitously. Ye continued to say and type out-of-pocket statements about Jewish people. He went on the podcast Drink Champs and bragged, “I can say anti-Semitic shit and Adidas cannot drop me.” Adidas then dropped him. Around the same time, the Gap (which had continued to sell products from a cobranded Yeezy Gap line even after Ye announced that he was terminating his two-year-old partnership with the retailer) pulled all Yeezy items from its stores and Web site, citing Ye’s recent public statements. By month’s end, Balenciaga, CAA, JP Morgan Chase, and Vogue magazine (a Condé Nast publication, as is GQ) had also cut ties with Ye.

This is more or less where the film leaves off; by the time Ye fired off the “death con 3” tweet, Ballesteros had also started to distance himself from his subject, less because of the growing controversies and more because he’d amassed a mountain of footage since 2018 and felt the need to bring the project to some kind of conclusion. They met and filmed sporadically after that; in the last third of the movie, the time-jumps between scenes become noticeably bigger, as if Ye is accelerating toward some career-derailment event horizon. Which he kind of was. In the years since Ballesteros finally stopped filming new material for the doc, Ye has veered into more and more indefensible territory while producing very little art worth separating from the artist.

As such, In Whose Name feels a bit like a time capsule. The Ye it depicts is unreasonable and impolitic and a bit of a screamer, but seems like a not-terrible hang in comparison to the Ye of 2025, a self-proclaimed Nazi who makes songs like “Heil Hitler” and “Cousins” (in which he claims to have engaged in sexual activity, at 14, with a cousin half his age) and seems to have recently exhausted the patience, or possibly the conscience, of the venal novelty rapper Dave Blunts, a collaborator who allegedly said, in a text exchange bringing their partnership to a close, that Ye was “very lost” and needed to “Find God.” We need not relitigate the other data points here: the “I LOVE HITLER” tweets, the Super Bowl ad directing interested shoppers to a Web site selling swastika-branded Yeezy t-shirts, the pileup of lawsuits from former employees and the disturbing allegations made therein, the rumors about Ye abusing both AI and nitrous oxide, or the YZY memecoin whose launch he announced after declaring that memecoins “PREY ON THE FANS WITH HYPE”—except to point out that all of those things happened this year alone.

Also this year, in March, when Ye met with the YouTube personality DJ Akademiks for a hotel-room interview, he arrived in street clothes before changing into a black Ku Klux Klan hood and robe and a bejeweled swastika medallion. In the video, he proceeds to unleash the full stream of his aggrieved consciousness circa 2025, alleging conspiracies against Sean “Diddy” Combs and Playboy Carti and “the kid from Linkin Park” and railing against enemies such as “the Jews,” “the whites above the Jews,” Universal Music Group chairman Lucian Grainge, Jay-Z and Beyoncé, “street n*ggas” and “faggot-ass celebrities,” the National Football League, Kamala Harris and Barack Obama, former GOOD Music recording artist John Legend (for “wearing sweaters in motherfuckin’ Barbados”) and even his late friend and collaborator Virgil Abloh. When Akademiks asks Ye a question about the Abloh beef—an unusual one, in that it seems to postdate Abloh’s death, of cancer, in 2021, an event Ye publicly mourned at the time—Ye responds simply, “I’m evil,” his voice under the hood as coldly venomous as the Riddler or the Zodiac speaking.

Akademiks is, let’s say, unprepared to steer this encounter toward substantive dialogue; over the course of an hour and change, he just kind of hangs on to the Grand Dragon’s tail for dear life. Akademiks does make one provocative observation, though, pointing out that Ye is proof that “cancellation” doesn’t work—and he is probably right about this, because few people have ever been more cancelled than Ye, and yet we will still be thinking about him for the rest of our goddamn lives, even as Ye keeps on pushing through to whatever unknown public status lies on the other side of cancellation, doing everything he can think of to render himself repugnant, as if trying to prove that whatever love America once professed for him was always false and conditional underneath it all.

In a silly interlude on The Life of Pablo, Ye rhymes knowingly about fans who moan about missing the “old Kanye” (and who lament “I hate the new Kanye, the bad mood Kanye.”) The one constant in our lives as Kanye fans is that there’s always a new Kanye around the corner. Past performance being indicative, this means that just as In Whose Name is enough to make you miss a Kanye who was actively becoming a pariah, a newer iteration of Ye may come along one day to make us miss the guy who made all that AI slop with Dave Blunts.

But you never know. Somebody told me he’s doing better of late. I’m as ready for this to be the case as I’ve been since 2016. One of my favorite artists of all time is Bob Dylan, who during his Christian period cursed the unbelievers of Sodom from the stage (and around the same time, told one rebellious audience, “You can go and see Kiss, and you can rock and roll all the way down to the pit!”); another of my favorite artists of all time is David Bowie, who in 1976 at the height of the Station to Station cocaine-bullet-train period he would later claim to barely remember, told a press conference “As I see it, I am the only alternative for the premier in England…I believe Britain could benefit from a fascist leader. After all, fascism is really nationalism,” and later called Hitler “one of the first rock stars” in an interview with young Cameron Crowe. Both Dylan and Bowie went on to write more chapters in their books; they also went through their cancellable phases before social media existed. When Bowie put out Let’s Dance in 1983 there was no way to Google “David Bowie + Nazi” like I did a second ago while writing this paragraph. Charlie Sheen is not one of my favorite artists, but even he’s on the comeback trail now, and it didn’t take that long. It felt like we talked about “tiger blood” for two solid years, but these days, who can remember?

Ballesteros tells me that he wanted In Whose Name to be more than a movie about Kanye West—that he wanted it to act as a mirror, a Rorschach test, not just a study of Ye’s downfall but something historians could watch in the future to understand the historical moment in which it took place. The finished film opens with the epigram “Dedicated to America, whatever that is,” from Kerouac’s Visions of Cody, a posthumously-published quasi-novel that revisits some of the same territory as On the Road, morphing Neal Cassady into the fictional “Cody Pomeroy.” Ballesteros liked what Kerouac wrote in the author’s note to that book: “Instead of just a horizontal account of travels on the road, I wanted a vertical metaphysical study of Cody’s character and its relationship to the general ‘America.’” That idea, Ballesteros tells me, after Googling the quote and reading it to me off his phone, “was my number-one inspiration.”

In its years-long engagement with its subject and the way its pace makes you feel the protractedness of that engagement even as the airplane-dream editing blurs the passage of time, Ballesteros’ film feels at least like a metaphorical expression of the defining characteristic of America’s relationship with Ye—our inability to stop paying attention to him, no matter how upsetting our enmeshment becomes, or how complicit it makes us feel in his downfall. What else the historians of tomorrow will get out of In Whose Name is hard to predict. Its perspective is pretty tightly locked on one particular American, albeit one who gets tossed around more than most by the tempest that is the last five or six years of American history. But maybe it’s a vertical metaphysical study of America in that the same powerful brain-warping forces that were waiting to bombard Kanye West the minute he stopped taking his medication—the cosmic rays of troll-farm ideology—are working on all of us, every day, and Ye is just one canary in a country-sized coal mine.

As Carl Jung is supposed to have said to James Joyce after analyzing Joyce’s schizophrenic daughter Lucia, “You are both submerged in the same water, but you are swimming, and she is drowning.” The fact that most of us don’t currently behave like Ye doesn’t mean we’re any less inherently vulnerable to the delusion that we’re not delusional. If there’s anything we should all understand after the last five or six years, either by observation of society or by observation of our own lives, it’s that it feels good as hell to slip into paranoid unreason if you can convince yourself you’re finally waking up. It certainly seems to feel good for Ye in this movie, except when it really, really doesn’t.

Ballesteros didn’t actually film inside of the Oval Office, by the way—the footage of the Trump meeting that appears in the movie is from a TV-news feed. But he was there on the ride in, sitting in the back of a bulletproof SUV with Ye, watching him demand to be admitted to the White House through the same entrance a visiting head of state would use, telling Jared Kushner over the phone, “I put my life in danger by wearing the [MAGA] hat and I need to be loved and respected as such.”

“I didn’t really feel a type of way for not being in the room,” Ballesteros says, “because I was like, ‘Well, that room”—and what was about to happen there—“is already so publicized.’ What always interested me was the quiet moments before and after those things.”

But in the movie, after the White House visit, even the quiet moments start getting pretty noisy. In Whose Name is also, in flashes, a close-up study of the Kardashian-West marriage as it frays; in one tense phone conversation, after Kim warns Ye that if he continues to burn bridges (by, for example, referring to the corporations he does business with as “slave ships”) he could wake up one day and have nothing, Ye screams at her, telling her to never put that idea out into the world.

This section of the film becomes a little movie unto itself about Ye screaming at women. Ye’s voice rings off the walls of Kim’s mausoleum-like Axel Vervoordt kitchen as he browbeats Kris Jenner about his hospitalization, asking “Did you have an effect on my mental health?”; Kris says yes, then breaks down crying. (Ballesteros is briefly visible here, a lanky shadow reflected in a window.) And then we’re in Uganda, in a makeshift recording studio inside some kind of glampy geodesic tent, watching Ye scream at his cousin, Kim Mitchell.

What’s at issue in this moment is murky—something about a possible threat to Ye’s life, and a difference of opinion between the security detail he’d brought with him and the local guys he’d hired on the ground as to whether it was safer to fly home immediately or spend the night in the bush and leave in the morning. Or maybe he’s upset because he’s been told he can’t broker a meeting between Ugandan president Yoweri Musveni and the opposition leader Bobi Wine.

But by only letting us catch what we can of that context, the film shifts the focus to the immediate impact of Ye’s paranoia—a common symptom of bipolar disorder—on the people around him. It’s unclear if any actual danger has presented itself but you can feel everybody’s cortisol levels spiking; Kim Kardashian seems to be coming to grips with the extent of her husband’s mental-health issues in real time, in front of Ballesteros’ camera.

“I remember thinking, ‘This will pass. This is just the moment,’” Ballesteros says. But he left Uganda early. When he landed at LAX, he drove straight to Big Sur, pitched a tent, and spent the night there, trying to process what he’d just experienced. Ultimately, he decided to keep following the story—“I feel like that’s what I’m called to do,” he remembers thinking, “and like that’s what [Ye] wants as well.”

Nick Jarjour says this dynamic continued throughout Ballesteros’ time with Ye. “The lifestyle and the excess mixed with the extreme episodes that he was experiencing every single day, mixed with the creative genius,” he says, “created this thing that he wanted to leave, but always wanted to go back to every morning.” Jarjour says he wrestled with the ethics of not stopping Ballesteros from going back into a situation that seemed to be taking a dark turn. After a while, he says, “it was almost like a wellness-check system that me and him had, where as long as he knows he’s got enough oxygen in the tank, boom—he’d go back down for another SCUBA mission.”

After Uganda we see Ye telling someone over the phone that he’s stepping back from politics to focus on architecture and parenting. These moments are a kind of refrain in the film; later, he says he’s getting out of the fashion industry to focus on schools and sustainable architecture. This is also a movie about a guy who’s decided that his job is revolutionizing things, and wanders the world looking for something to revolutionize. Ye seems to be forever in search of some new arena he can enter where what he has to offer will finally be properly valued; when he’s not immediately greeted as a genius, or encounters any friction at all, it proves every point he’s trying to make about the forces arrayed against him, and soon enough it’s on to the next arena. One battle after another.

He’s also, seemingly, forever searching for some higher calling to surrender himself to. First it’s Trumpism. Then it’s God, via his “Sunday Service” events at Coachella and elsewhere. He goes to Houston, where he speaks at Joel Osteen’s megachurch but also leads a gospel choir inside the county jail. The incarcerated worshippers wear orange, the choir wears blue. Like the Sunday Service sequences, the scene is a reminder that even after he put on the red hat, Ye could still create moments of striking beauty, reaching in his art (in his music, yes, but also in the clean and minimal and aesthetically-unified look and feel of his stage presentations, his clothing and shoe designs, and the interiors of the spaces where he lives and works) for a degree of calm and spaciousness and order he seems utterly incapable of cultivating in his actual life.

The Jesus period is just a moment, though. It doesn’t last. In the film Ye always seems to be building something and abandoning it, like the futuristic moon-colony we see him constructing in the wilds of Wyoming (on property since “left to rot,” per one tabloid.) He ramps up again. In 2020, on the Fourth of July, he announces he’s running for President as a third-party candidate, despite it being too late for his name to appear on the ballot in at least six states. At one campaign event, he gets onstage in a bulletproof vest in Charleston, South Carolina, rails against guns and porn and Percocet, and breaks down scream-crying about how he and Kim almost made the decision to abort North: “I almost killed my daughter.”

In 2021, reportedly under contractual pressure to deliver a finished version of his tenth album Donda to Def Jam/Universal, he moves into Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta, paying (again, reportedly) somewhere between $150,000 and one million dollars a day to live in a locker room and work around the clock until the record is finished. We watch him go off, James Brown/Buddy Rich style, on some of his Donda guest rappers for not taking the mission seriously; Rick Rubin sits behind him, approvingly bobbing his head as if this rant is Ye’s new music, and on some level, who’s to say it isn’t? Eventually a listening party does occur—he burns down a replica of his childhood home, he stages a surreal mock wedding with his soon-to-be-ex-wife Kim as a veiled corpse-bride, he sets himself on fire.

And Marilyn Manson’s there, for some reason, hanging out on the replica porch of Ye’s replica house. Why the fuck is he there? His presence robs Ye of whatever shred of moral authority his crusade against cancel culture might have had. When Donda launched, Marilyn Manson wasn’t cancelled because liberal society couldn’t handle his ideas. Marilyn Manson doesn’t have ideas. Marilyn Manson was considered cancelled, in that moment, because he’d been accused of psychological and sexual abuse by at least six women, including his former partner Evan Rachel Wood. But his presence does give Ballesteros’ film its best comic-book-movie image—a low-angle shot of Manson, Playboi Carti in Pennywise clown makeup, and the stylist Burberry Erry, a punk with an enormous head of liberty spikes, looking down at Ye from the top of a small flight of stairs. They look like supervillains, seemingly beckoning him to walk up there and take his place in their Legion of Doom, to join them on the Dark Side of the Force. Manson doesn’t seem to have become a fixture of Ye’s world, but they hung out a couple of times and since then Ye’s entered the Going Door To Door Trying To Shock People phase of his career. I refuse to believe this is entirely coincidental.

Ballesteros imagined Donda might be the end of his movie: Ye survives it all and turns his album rollout into a darkly majestic opera depicting the loss of his marriage and his public immolation, turning personal devastation into an aesthetic triumph. It would have made for a nice, clean arc. But then “death con 3” happened, and the Adidas and Gap deals blew up, and that became the climax of the story instead.

By then, Ballesteros says, he’d already started to feel like whatever story he’d been telling was approaching a natural endpoint. He rattles off events that felt like signs: Virgil Abloh had died. Ten fans had been trampled to death at a Travis Scott concert. The whole zeitgeist Ballesteros had once yearned to capture in a film seemed to be dissipating. Even the Yeezy office in Calabasas closed; temporary spaces came and went after that, and for a time Ye worked out of a warehouse in downtown Los Angeles. Ballesteros went there on occasion, and it’s there that he captures a great moment in which Ye decides to prove he’s not an anti-Semite by bringing out his Jewish friend, who turns out to be cancelled American Apparel founder Dov Charney. But it wasn’t the same; there was no longer a fixed center to Ye’s universe.

Maybe more importantly, Ballesteros wasn’t the kid who’d walked into the Energy Center with a night-vision camera and a dream anymore. He’d begun to think of his unmade movie as a coming-of-age film, even if its autobiographical component would never be apparent to anyone but him; having now come of age, he felt it was time to close the book on the story.

By then Ballesteros had attracted his own coterie of culture kids, people he trusted and had tried to bring along professionally, he says, “in the same way that I saw Virgil develop people, in the same way I saw Ye develop people.” One of them was Jack Russell, another aspiring filmmaker who’d moved to L.A. from Idaho a few years earlier and pestered Ballesteros with replies to his Instagram stories until finally Ballesteros broke down and said, Let’s meet.

Ballesteros was renting a tiny house in Pacific Palisades, steps from the beach; they called it The Dojo. Toward the end of Ballesteros’ time with Ye, he and Russell became roommates there, and Russell took it upon himself to start logging and organizing all of Ballesteros’ Ye footage, which at the time was stored on over fifty different LaCie hard drives scattered around the Dojo.

“That was my job,” Russell says, “because no one wanted to do it. Nico, basically, psychologically, couldn’t do it. He was like, ‘I just can’t relive my own life in totality again. It’s just so overwhelming.’ So I was like, ‘I’ll do it. I’ll watch it all, label it all, put it all in order, figure out which hard drive it’s on, make sure it all links together.”

In the summer of 2022, after taking about five months off from filming the movie, Ballesteros went to see Ye, who was staying at a hotel in Los Angeles. He didn’t film; they just talked. Ballesteros told him about the footage he and Jack had been logging, acting out scenes: And then you said this, and then Jacques Herzog said this. And Ye listened, and then said, “We got to start filming again.”

Ballesteros said, Definitely.

The last leg of the journey might have been the most intense phase of the process. “We would go to London, and then we’d be back in LA, and then we’d go to Paris, and we might go back to London. We’d go to Tennessee and then we’d be back in LA. We went back and forth between Europe and LA, I kid you not, probably 20 times in the span of three weeks, or something wild like that.” Ballesteros remembers sleeping on a lot of planes, touching down in three or four time zones over the course of a few days; things got pretty blurry.

“I was there with him in some of the most exhausted states of mind toward the end,” Jack Russell says. “I could see, visibly, how tired he would be, and I don’t know how he would do it. He would wake up at 7:00 AM and get back at it the next day.”

At some point Russell finished cataloguing everything Ballesteros had shot to that point; having caught up, he’d ingest each day’s new material, living Nico’s life on a one-day delay. “It was like, ‘You can go out and shoot, and just know I’ll be here labeling and cutting what you did the prior days, and when you get back I’ll make sure there’s some food to eat. I’ll even make sure your bag’s packed, whatever,’” Russell says. “I was kind of just holding down those little details just so he could keep going.”

Ballesteros remembers being in New York with Ye around this time, asking him “Have you ever thought about how long you may want me to film you?” Ye thought about it and said, “I was just thinking, maybe one day North grows up”—meaning, in his mind, eventually Ballesteros would be there (with an iPhone 46 or whatever) to document that, too.

“I remember, I was just like, ‘Yeah!’ I was just so in it,” Ballesteros says. “I was like, ‘Yeah, man—that could be a part of the story.”

It could have gone on forever: Ye living his big and ever-more-complicated life, Ballesteros bearing witness, Ye forever doing or saying some new crazy thing that would change what that story was, and Jack Russell back home in the dojo, logging footage, keeping Ballesteros fed and logistically backstopped. A stable system. In a way, “death con 3” and its cascading consequences gave Ballesteros his life back.

“I was like, ‘Well, this is an end to the story, for now.’ I felt called to take a step back,” he says. “I was like, ‘All right. I’m going to go edit the film now.’”

He’d been getting calls from reporters looking for comment on Ye’s situation; he changed his phone number, got off social media. He went home for Thanksgiving, drove north to Carmel and stayed at the La Playa, the resort hotel where Steve Jobs unveiled the prototype of the Macintosh during a retreat with his Apple development team in 1983; the ensuing celebration, which involved alcohol, a beach bonfire, and skinny-dipping, got Apple banned from the place for almost 30 years.

It was there that Ballesteros decided he needed to get out of the country. “I feel like in order to tell this story,” he told his team, “I need to get out of America, because it’s such an American story that I need to reset.”

So Ballesteros, Russell, and a third friend-turned-story-editor—a theater actor and writer named Shy Ranje who Ballesteros had met in 2019 and bumped back into years later—packed everything (the hard drives, a server, some ultra-wide monitors) into padded Pelican cases and took everything to a house in the jungle down in Costa Rica, where they worked on the movie for an entire year.

This was partly a security measure; in the wake of Ye’s public implosion, plenty of media outlets would probably have killed to get their hands on 3,000 hours of unedited Ye footage. (When I meet Ballesteros, all that material is under lock and key in a vault in Beverly Hills, like in the Gatlin Brothers song about all the gold in California.) But why Ballesteros and Co. felt it necessary to get this far away—why they decided to take their hard drives to the fucking jungle for a year—is harder for everyone involved to explain.

“I don’t know if there really is a cohesive, sensible answer,” Jack Russell says, when asked why they couldn’t have just moved their operation up the 405 to Pacoima and put their cell phones in a drawer. “It was not, in hindsight, super logical or easy, as far as transporting the hard drives and computers. That was a big part of the story in the beginning—just, logistics.”

“It was just this big thing,” he says. “We set off into the world. I think we did it for the story, in some ways. I wouldn’t say I could say that for Nico, but it felt that way.”

“I was honestly just really inspired, I guess you could say, by people like Kanye,” Ballesteros says, “and [his] idea of, ‘We gotta go to Hawaii to make the album.’ So, I was like, ‘We got to go to Costa Rica.’”

A year flew by. After that would come a gradual process of reintegration, of bringing the movie together and bringing it into the world—Ballesteros decided that having spent that time in the jungle, they needed to go to the desert, and that’s when they taped all those strips of paper to the wall in Palm Springs, and then after that they holed up at the Chateau, and Ballesteros and Justin Staple sat with a six-hour cut of the movie, carving it down to size, and in time they had something Ballesteros could show to other people.

That part of the process—showing it to people, hearing what they think—will continue through opening weekend, when Ballesteros will bounce around watching it on different big screens in theaters all over town, with audiences that he’s surprised to discover are full of teenagers, kids around the age Ballesteros was when he watched the Life of Pablo livestream at that Santa Ana AMC. At one screening he’ll get recognized after it’s over; one of those kids in the crowd will ask him to sign a copy of Ye’s Graduation, an album that came out when Ballesteros was seven years old, as if he’d had something to do with making it.

It’s possible that those teenage fans are an endlessly renewable resource, that as long as there are new culture kids coming of age and looking to define themselves, Ye will never stop making new fans. Whether any of those fans will make anything as profound as In Whose Name is harder to say. At one point in our conversation Justin Staple points out that by enlisting someone to film him all day every day, Ye anticipated the rise of the “streamers”—the Kai Cenats and IShowSpeeds of the world, who’ve made always-on reality shows from just hanging out and doing whatever.

Ye himself has spent some time in front of streamers’ cameras of late, as if he misses being the subject of someone’s endless movie. He used to have Nico; now he has Sneako. It feels like a downgrade. Streamers, by definition, exist to pull eyes and fill time and build brands, nothing more. Narrative isn’t the point; scale and reach and sponsorship deals are. The camera is just there to feed information to the Internet, to the chat. It’s not there to capture—or, at any rate, no one will ever bother to ingest what it records and place it in context or arrange it into a story. In the end, In Whose Name is a sad movie not just because it’s a record of a genius blowing up his whole life through a series of unforced errors, but because it may be the last time anyone puts this much time and care into presenting his life as a story. Ye is an irresistible subject and there will always be someone else ready to point a camera at him—but it’s hard to imagine he’ll ever be seen quite this clearly again.