By Yohji Lam

Copyright scmp

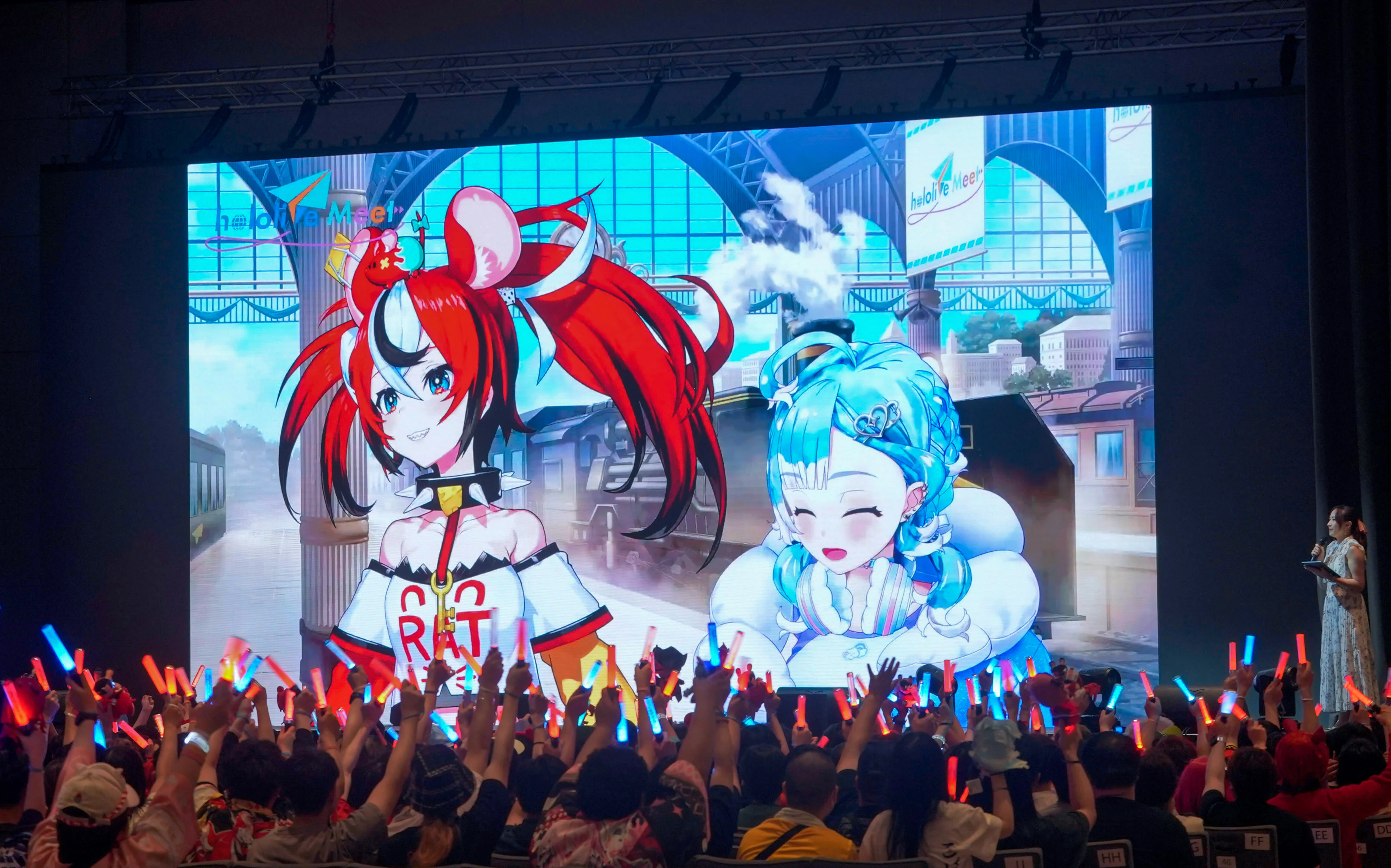

On a humid summer day, a long queue of people snakes outside a hotel ballroom turned concert hall in Wan Chai, Hong Kong, light sticks in hand.

But they are not waiting for a chart-topping Cantopop star nor a viral K-pop sensation. Instead, this is a concert headlining virtual YouTubers, or “VTubers”.

Originating from Japan, a VTuber is an online persona that uses a virtual avatar, typically an anime-style character, to create and stream content. The person who controls the avatar in real time using motion capture and face-tracking software remains anonymous.

Although the name reflects its YouTube roots, VTubers are found on various digital platforms such as Twitch, Bilibili and TikTok.

They play games, sing and interact with fans in their live streams, and their connection and bond with their followers is often described to be “more real” than that between traditional celebrities and their fans.

Some VTubers operate as independent content creators, managing all the work themselves, while others join agencies such as Tokyo-based Hololive, considered the world’s largest of its kind, with 89 talents and more than 97 million subscribers in total.

For its sold-out Hong Kong concert and other meet-and-greet events in July, Hololive brought 11 of its talents to the city.

The lights dim and the concert finally gets under way. The crowd erupts and the Wan Chai venue instantly turns into a sea of orange light sticks.

Showing their appreciation for the rapturous reception, the VTubers address the crowd: “Hey Hong Kong, sing with us! All of us, synchronise!”

The energy is palpable – the event is a celebration of belonging, hope and shared dreams.

“I’m so flabbergasted,” says Max Jackowski, a fan who cannot hold back his excitement after the concert. “I’m euphoric, that’s the best way to put it. Hololive gives me hope.

“VTubers are such an egalitarian medium of entertainment where you’re not constrained by just shallow aesthetic appearances. [They] can create something wonderful, beautiful and magical [that] connects [them] with the fans.”

The influence VTubers have on their fans cannot be understated. Collectively, they muster more than 50 billion annual YouTube views. VTubing provides fans a sense of community, purpose and even a reason to keep going.

“[The phenomenon] allows me to continue to live,” says Rainy Chan, a fan of a local VTuber. “They are a highlight of my life,” echoes VTuber fan Sakura Yip.

MM Liu, a Dutch VTuber fan, says: “It’s become its own subculture. For many people, it’s a way to connect, literally, connect with each other.”

This acute need to connect became apparent during the Covid-19 pandemic when the world went digital during lockdown.

Social isolation and a relentless work culture have driven many young people to VTubers who – with their regular streams and openness to share their own struggles, often facilitated by their anonymity – have become a new kind of companion. And they are just a click away.

VTubers interact with their audience in real time, reading comments, accepting donations, responding to jokes and even sharing their own vulnerabilities. While the relationship is parasocial (one-sided) on a technical level, it feels reciprocal to some extent, and the interaction helps forge deep bonds between creators and their fans.

“Compared to traditional celebrities, VTubers feel much more accessible and relatable,” says Hololive founder and president Motoaki “Yagoo” Tanigo. “VTubers can engage with audiences in a much more personal way.”

Emotional engagement aside, VTubing is a big business. Hololive amassed 43.4 billion yen (US$301 million) in sales in the financial year ending March 2025. Tokyo-based QY Research projects the global VTuber market will hit nearly US$4 billion annually by 2030.

Other than receiving donations online, revenue is generated through official and doujinshi (self-published works) merchandise, commercial collaboration, and even things like Octopus cards featuring VTubers in Hong Kong school uniforms.

Some fans create their own videos, memes and music to catch the attention of their favourite VTubers and fellow fans.

“Biboo tax”, a meme video created by Hololive fan Ludokano, went viral and was adopted by VTuber Koseki Bijou as her anthem.

Hololive later partnered with Ludokano to create visuals for other official music videos.

For Gordon Yeung, a VTuber fan who also does content creation and filmmaking, the goal is simple.

“I hope that one day, I get to collaborate with Hololive officially, to spread VTubers to the ends of the world, and let people know how Hololive or the rest of the VTubing industry encourages and tugs at one’s heartstrings, able to save a lot more people who may feel isolated.”

The impact of VTubers extends beyond solace and emotional support.

In July, Ironmouse, widely considered to be the world’s biggest independent VTuber, raised more than US$1 million for the Immune Deficiency Foundation within 48 hours.

“Her authenticity, her vulnerability, inspired me,” says Jorey Berry, president and chief executive of the Immune Deficiency Foundation, in a YouTube statement. “You made a difference.”

Ironmouse herself suffers from a severe immune disorder that has left her bedridden and housebound in between extended hospital stays – a story that resonates deeply with her fans.

She has even inspired fellow content creators to hold fundraising events of their own.

“I’m just really glad that we could somehow support the Immune Deficiency Foundation so they could be there for other people like me, and they don’t have to go through the same thing that I went through,” says Ironmouse on a tablet screen brought on stage, tearing up as YouTuber Connor “CDawgVA” Colquhoun concluded their two-week cyclathon across Japan.

Dokibird, an independent VTuber who organised a similar charity event for the Brain Behaviour Research Foundation in 2024, believes that the motivation of fans donating could be summed up in one sentence: “It’s literally saving lives, and we want to save lives!”

For Nerissa Ravencroft, who is managed by Hololive’s English-language division, being a VTuber is an opportunity to realise her dream of being a voice actor.

“For a long time, I really wanted to be a voice actor. Instead of just doing voice acting and playing a character, I get to be a character all the time, and that sounds really, really fun,” she says.

For most VTubers, if not all, anonymity remains the core of their being. With great intimacy and connection with their fans often comes great risk. Doxxing, for instance, is a persistent threat.

But for fans like Yeung, not knowing who is behind the voice is not an issue.

“It doesn’t matter who they are. Who cares?” he says. For him, it is about their personality and soul, their voices, and the joy they exude.

While there are worries about fans blurring the boundaries between support and obsession, experts suggest that the artificiality of a VTuber persona could act as a buffer.

“Real idols, I think, are always held to impossible standards. But VTubers are already beyond the realm of the real,” says Dr Isaac Gagné, a principal researcher at the German Institute for Japanese Studies in Tokyo.

“Fans tend to be fully aware that the VTuber avatar is a construction. In this sense, the VTuber avatar really can’t betray them because it is already artificial.”

VTubers may be virtual, but their impact is real as measured in lives touched, communities built and hope restored.

“I hope this Japanese culture will continue to spread and grow, and that the term VTuber will become more widely known,” says Kakinuma Takeru, a Japanese fan who came to Hong Kong for the concert.

“This is a culture that Japan can be proud of, so please continue to do your best every day.”