Nine-year-old Donald Cook knew he had to react quickly as the fire engulfed the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus big top in Hartford on July 6, 1944, known as one of the most devastating fires in the state’s history.

Separated from his mother and his siblings high up in the bleachers, Linda Cook, his wife, and daughter, Heidi Loomis, recounted how Donald Cook ran across the backs of the bleachers when he saw an opportunity to drop down and get out under the tent.

The act helped him survive the horrible blaze that killed 168 people and injured more than 700. The death toll included 59 children who were 9-years-old or younger.

Loomis said she admired her father’s bravery and quick thinking that enabled him to find safety as a child.

The day the clowns cried: The story of the Hartford circus fire

His mother, Mildred Cook, insisted on taking her other two children, Eleanor Cook and Edward Cook in a different direction. Both children perished in the fire while Mildred Cook sustained severe burns, according to the Cook family.

“He wanted them to go with him because he was a sharp little kid and he could see that he could get out the other way,” said Linda Cook, explaining that Mildred Cook and her children were close to the origin of the fire.

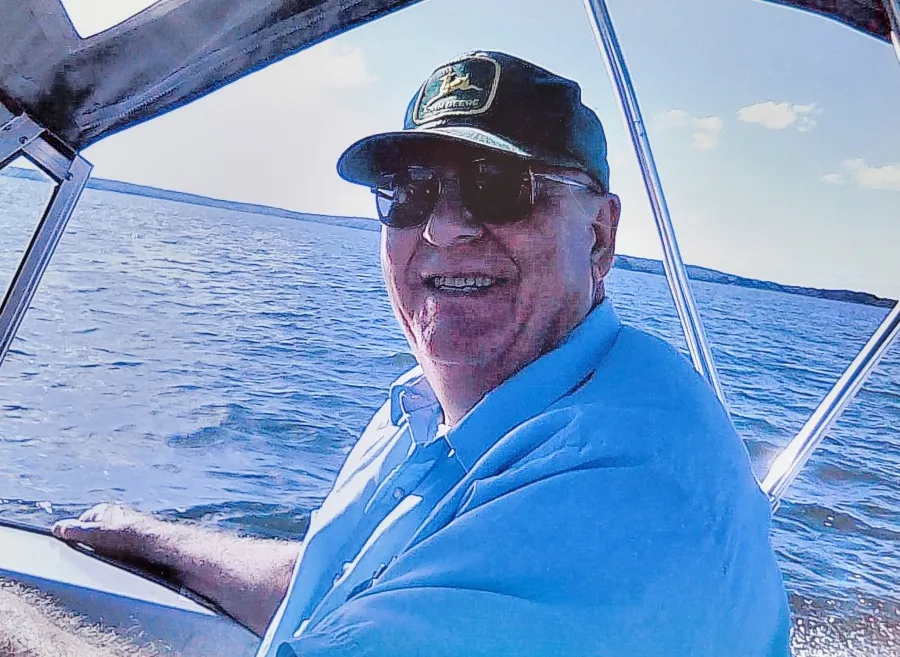

Linda Cook and Heidi Loomis reflected on Donald Cook’s life as a survivor of the fire and the longstanding impact it had on his life as the now Madrid, Iowa resident died Monday at the age of 90.

Natalie Belanger, public programs manager at Connecticut Museum of Culture and History, said in the wake of the fire Connecticut adopted much stricter fire codes and oversight of outdoor structures like tents.

According to eyewitness accounts, the 48-foot tall big top burned in less than 10 minutes. Flaming canvas, sealed with gasoline and paraffin wax, burned some to death. Extreme heat suffocated others and the ensuing panic also resulted in trampling deaths.

An investigation after the fire showed that there were 30 pails containing 12 quarts of water each beneath the bleachers, only a few of which were used in an attempt to stop the spread of flames. None of the circus’s 36 fire extinguishers were inside the tent that day, according to witness statements.

Even though Ringling Brothers carried only about $600,000 in liability insurance at the time of the fire, it would go on to pay just shy of $4 million in claims for the families of 698 dead and injured who filed claims. The last payment to families was made in 1950. The last legal action was taken in 1969, when the award to the late Charles Tomalonis was turned over to the state because he had no heirs.

Little Miss 1565

Linda Cook shared the impact the fire had on her husband’s mother.

While Edward Cook was immediately determined to have perished in the fire, Eleanor would not be identified until 1991.

Six unidentified victims in the aftermath of the fire were all buried with their morgue numbers in a cemetery in Windsor, Belanger said.

“I can tell you that she lived with guilt for her entire life until she was identified in 1991,” Linda Cook said. “She always harbored that little thought that Eleanor had been taken in by another family and raised by another family. She always harbored the thought that the little girl had lived.”

Eleanor Cook, known as “Little Miss 1565,” was identified in 1991, Belanger explained. The name was given by Hartford detective Thomas Barber, who was at the circus that day helping to rescue people and later identify victims at the morgue.

“He was obsessed with the identity of Little Miss 1565,” she said, adding that the museum includes an archive belonging to Barber. “We have collections of letters from around the world of people who wrote to him touched by his vigilance.”

Belanger said that Barber’s research was picked up by the Hartford Fire Department who identified Eleanor Cook in 1991.

After the fire Donald Cook was raised by his aunt and uncle in rural western Massachusetts, according to his obituary.

He attended Springfield College before being drafted into the U.S. Army where he spent 18 months in North Africa as a topographic “surveyor” with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers,” his obituary further states.

His family said he spent his life in sales where he managed the maintenance of a 4,000 car fleet of long-term lease vehicles.

“He was very congenial and very friendly,” said Linda Cook. “He could read people and adjust to their personality.”

A big loss

Growing up without siblings, Linda Cook said it certainly affected her husband’s life.

“He rarely talked about it and his daughter knew nothing about it for a long time,” she said. “The loss of his sister and brother really impacted him greatly.”

The family moved out of Connecticut and lived in several states over the years including Indiana and then finally Iowa, his wife explained.

Loomis said the loss shaped her father’s determination and resilience.

“He taught us to never give up on anything,” she said. “He was self taught in a lot of things. He was very personable.”

Loomis recalls that the experience made him cautious about fire and that he was not a fan of large crowds.

More than 160 died, hundreds injured: One of last survivors of Hartford circus fire recalls July day

“Whenever we were in any kind of large group such as the theater or anything of that sort he always wanted to sit on the end,” she said. He always wanted to know how you would get out of a place.”

This example taught her to be vigilant herself concerning fire safety and exits, she said.

“To this day I am very aware of fires,” she said. “I don’t burn candles and things like that. I never go out of the house without turning the dryer off. It did have an effect on both my sister and I.”

Overall, Loomis said the fire made the family stronger and aware of things.

Belanger said the fire was a preventable tragedy.

“It was the type of disaster that required a lot of different institutions failing,” she said. “It is still unsettled whether it was an arson or an accident. Even so, the scale of injury would not have been as great if regulations had been enforced. There were some regulations in the city of Hartford relating to tent safety that were not enforced that day. There were also safety rules that the circus had in place that they did not carry out.”

The Connecticut Mirror and earlier reporting from the Hartford Courant staff contributed to this report.