By Tom McTague

Copyright newstatesman

I write this note from a room with one of the best views in London. Stretched out beneath me lies the Thames, shimmering in the dark as it flows slowly past, the sun long since set. Ahead of me, I can see Lambeth Bridge and the new Vauxhall skyline beyond, the dark outline of Battersea Power Station just visible to the right. Where am I, you might wonder – a fancy hotel? A plush new set of offices for the New Statesman? Alas, no: bed ten in the Nightingale ward of St Thomas’ hospital, the beauty of my view somewhat dimmed by the rhythmic snorts of discomfort emanating from the bed opposite.

This was not the start of the week I was expecting. An almost-imperceptible splinter in my thumb had become inflamed, but I hadn’t thought much of it. By Friday it had become swollen and sore, but I thought I would try a little DIY surgery to remove the blighter rather than brave a visit to the doctors: a pair of tweezers soaked in salted boiling water would do the trick, I thought. But by Saturday night, it was clear my surgical skills were not as effective as I’d hoped. A trip to A&E beckoned. Still, I assumed an overworked doctor would deal with my clownishly large thumb with a quick slice of their scalpel and see me on my way with a bag of antibiotics. To my alarm, I was sent to “plastics” at St Thomas’, whereupon said clown thumb was numbed, sliced open and cleaned out (the burning sensation of the antiseptic off-puttingly perceptible under the anaesthetic). I was then told I would be staying first for one night and then another.

Dosed with regular shots of morphine and with a cannula in my arm, which was hoisted above me, I was confined to hospital for almost three days. The reason, I was told, was that the infection looked to have spread up my arm. Lines were drawn in pen – borders that the infection could not cross. Thankfully, it didn’t.

This experience has left me with a few half-formed thoughts. The hospital’s A&E was predictably grim. The “waiting time” clock when I arrived at 3am on Sunday morning suggested I wouldn’t be seen for more than eight hours. Three men, seemingly high on drugs, stumbled around giggling hysterically, while others waited in silence, worried. A policeman loitered. In the end, I was seen and home within four hours. And still, I had not been treated. The doctors did not feel they had the required specialism to treat me. Instead, I had to book an appointment at St Thomas’ at 11am.

When, around 2pm, I was eventually seen by the doctor, a young German man, I asked him what he thought of the NHS. The emergency treatment was much the same as in Germany, he said, but the bits around the edges were worse. “Which bits?” I asked. “A&E,” he said. He felt that doctors in Germany took more responsibility earlier, so cases like mine would be dealt with sooner.

I do not know how accurate this assessment is – I would be interested in readers’ thoughts – but it seemed to carry a certain truth. Once upon a time, didn’t GPs carry out minor surgeries? Why is this no longer so common? Perhaps it is part of a wider cultural shift: it can certainly feel as though we have become a nation of disempowered middle men and women whose jobs largely involve passing on tasks to the right people. They are to blame. We are powerless. And so we rage when nothing seems to work any longer.

These inchoate feelings of frustration apply across much of life: not just to A&Es, but the housing market, universities, prisons and social care. In politics, the same sense of powerlessness pervades. Keir Starmer does not look in control, nor Rachel Reeves, nor Shabana Mahmood. In fact, no one looks as though they are in charge.

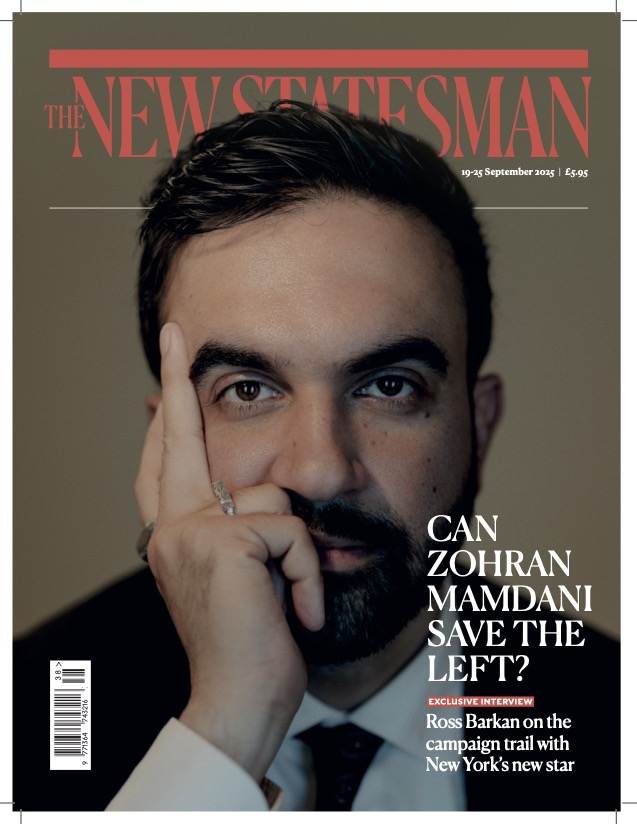

This helps to explain the appeal of figures like Zohran Mamdani, the Democratic candidate to be mayor of New York City and the subject of this week’s exclusive Cover Story. As Ross Barkan writes, Mamdani’s policy agenda is exciting to ordinary voters because it offers “an indisputably clear vision of tomorrow”. Like him or not, “his supporters and detractors know exactly what he stands for”. In other words, Mamdani looks as though he is in control of his agenda. His policies are simple: rent controls, cheaper groceries, and free buses and childcare. He identifies problems and offers solutions. Whatever their merits, they are policies that suggest politics can achieve things and isn’t merely a form of management. He takes responsibility. There are lessons for all of us in that.