Copyright forbes

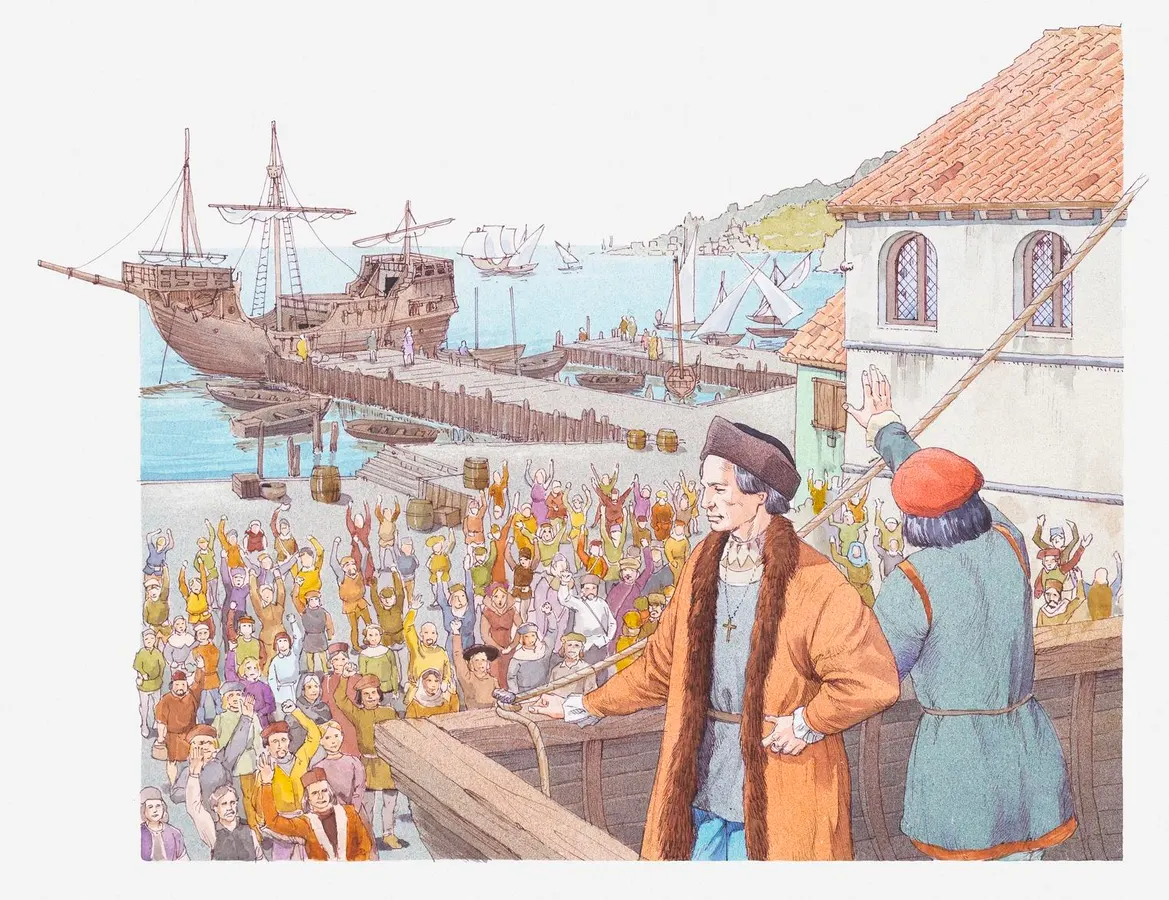

When we think about the “Columbian exchange,” much attention is paid to the diseases that were brought from the Old World to the New World. But disease transmission is always a two-way street. A biologist explains. The Columbian Exchange refers to the vast transfer of plants, animals, people and pathogens that followed Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the Americas in 1492. When most people think of this process, they picture the catastrophic diseases that decimated Indigenous populations: smallpox, measles, influenza, and bubonic plague. But often, biological exchange is never one-directional, much like trade itself. Some organisms traveled eastward as well. And one of them, a spirochete bacterium likely native to the Americas, caused what may be Europe’s first recorded sexually transmitted pandemic: syphilis. The Mysterious Origin Of Syphilis The disease now known as syphilis first exploded onto the European scene in 1495, when soldiers besieging the Italian city of Naples began suffering from grotesque sores, painful ulcers and systemic lesions that left many disfigured or dead. Contemporary accounts describe an affliction so virulent that it rotted the flesh within months. Within just a few years, it had spread across the continent. But where did it come from? As research from the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases denotes, for over a century, historians and scientists have debated between two main theories: The Columbian Hypothesis. In this framework, syphilis is believed to have originated in the New World, after being brought to Europe by Columbus’s crew upon their return in 1493. The Pre-Columbian Hypothesis. This framework suggests that the bacterium for syphilis existed in the Old World all along, only in a less virulent form. It’s believed to only have become more severe due to environmental or genetic changes. Today, most biological and paleopathological evidence points to the Columbian hypothesis being most likely. Skeletal remains from pre-Columbian Native American sites — particularly those in the Caribbean and coastal South America — show bone lesions that are commonly linked to treponemal diseases. Specifically, this is a family of diseases that includes yaws, bejel and, of course, syphilis. This theory only becomes more attractive upon recognizing the lack of convincing evidence of syphilis-like pathology in pre-1492 European remains. MORE FOR YOU How A New Pathogen Found Fertile Ground To understand why syphilis spread so explosively in Europe, we need to look at both biology and social behavior. The pathogen Treponema pallidum is a spirochete: a corkscrew-shaped bacterium with a helical structure that allows it to burrow through human tissues with remarkable, terrifying efficiency. Under the microscope, it looks almost like a metallic thread that vibrates constantly with motion. But once it makes its way inside the body, it can actually remain dormant for years. In turn, it can effectively evade immune detection by means of frequently altering the proteins on its outer membrane. This molecular “shape-shifting” makes it one of the most elusive pathogens known to medicine. Columbus’s crew introduced this bacteria to Europe at a point where the population had no immunological history with it. This resulted in a perfect storm: a naive host population, a highly transmissible pathogen and social conditions — crowded cities, armies and brothels — only made it easier for it to spread rapidly. The matter was only worsened by the fact that the late 15th century was a time of unprecedented human mobility. Armies were moving across the continent during the Italian Wars, which means they carried the disease with them from Naples to France, Germany and beyond. It is suggested that the Italians blamed the disease on the French, the French blamed the Italians — all the while both populations were actively contributing to its spread across the entirety of Europe. Evolution In Real Time Interestingly, this early strain of syphilis from the Columbian Exchange seems to have been significantly more aggressive than modern-day strains. Historical accounts suggest symptoms developed within weeks, and were more often than not fatal. However, the disease evolved into a milder but more chronic form in the decades that follow. This, eventually, became the syphilis that we know of today, with primary sores, secondary rashes and a long latent phase. From a biological standpoint, this makes sense. Pathogens that kill their hosts too quickly limit their own opportunity to further transmit and thrive. In this sense, natural selection favors less virulent strains — those allowing hosts to remain sexually active for much longer — which is essentially what allowed the STD to become what it is today. In effect, the disease “learned” to persist, rather than to burn out too quickly. This also mirrors patterns seen in other infectious diseases, where initial outbreaks in new host populations are severe, but which tend to stabilize over time. This is a quintessential demonstration of what biologists call the “trade-off hypothesis.” This is the idea, as research from the Journal of Evolutionary Biology explains, that most pathogens evolve to balance transmission efficiency against host mortality. Global Ripple Effects By the early 1500s, syphilis had spread to Africa and Asia, only to eventually make its way back to the Americas via European colonizers. Ironically, the disease most probably returned to its evolutionary homeland in a new and much more virulent form. The global network of exploration and trade ensured that the “return flow” of disease was just as real as the westward transmission of smallpox. Medically, syphilis became one of humanity’s great scourges. Since penicillin, the antibiotic it’s most commonly treated with, was only discovered in the 20th century, it caused immense suffering until then. As a result, it was blamed for neurological disorders, blindness, miscarriages and congenital deformities. Its social stigma inspired everything from Elizabethan poetry to the rise of specialized hospitals. Even today, syphilis remains a serious public health challenge. The World Health Organization estimates that over 7 million people are infected with syphilis every year — mostly in low- and middle-income countries. And because T. pallidum still isn’t easily cultured in lab conditions, so many aspects of its biology remain mysterious to us all these centuries later. The scourge of syphilis reminds us that when humans move, microbes move with us. This is precisely what made the Columbian Exchange such an ecological upheaval: microbes, plants, and animals were all thrust into novel environments, and each of which was forced to either adapt or perish. For T. pallidum, the voyage across the Atlantic was an evolutionary jackpot. It found a massive, unexposed population and a reliable transmission route (sexual intercourse) that guaranteed persistence. Perhaps more than the idea of disease transmission, climate change has the power to change demographics. How worried are you? Take the science-backed Climate Change Worry Scale to know how your fear compares with others. Editorial StandardsReprints & Permissions