Chinese AI developer iFLYTEK would have been happy to use American Nvidia chips to train a large language model that rivals ChatGPT, but says it’s now doing just fine without them.

Work on alternatives started when iFLYTEK was blacklisted by the U.S. Commerce Department in 2019 during President Donald Trump’s first presidency and before broader restrictions on the export of the most advanced AI chips to China imposed three years ago, amid fears for U.S. national security over technological advances by America’s biggest strategic rival.

“We overcame that difficulty,” iFLYTEK’s Chen Cheng told Newsweek and other foreign reporters on a Chinese Foreign Ministry-organized visit to Hefei, in the eastern province of Anhui, and other businesses in the Yangtze River Delta industrial hub.

The way that Chinese companies have developed their own advanced chipmaking industry and domestic alternatives to Nvidia’s AI chips underlines the challenge facing U.S. attempts to contain China’s business and technological advances in the race for world-beating artificial intelligence as well as in everything from electric vehicles and batteries to solar power generation and drones—with inevitable implications for the strategic balance as well as for global business competition between the United States and China.

“There are lots of areas where you could say that the containment policy has actually just given China a new lease of life to prove that it can continue to aspire to all the things it aspires to, but not relying on foreign imports and foreign technology,” said George Magnus, research associate at Oxford University’s China Centre.

“It may be that it satisfies American conscience to say: ‘Well, we’re not selling them our best stuff, our best kit.’ But I don’t think it necessarily means that the Chinese can’t compete,” he told Newsweek.

Rapid Change

Four days spent criss-crossing the Yangtze River Delta by high-speed railway to visit Chinese businesses gave an indication of the pace of change in the region that is one of the hubs of Chinese technology development. The provinces of the delta alone have an economy larger than Germany’s—the world’s third largest—and some 240 million people, more than two-thirds of the U.S. population.

The White House did not immediately respond to a request for comment on the effectiveness of its measures to curb technology exports in addition to tariffs imposed under Trump that have made trade unpredictable for businesses.

Commerce Department sanctions on iFLYTEK came into force in 2019 over its alleged role in the oppression of Muslims in China’s far-western Xinjiang region using high-technology surveillance. China rejects the U.S. accusations.

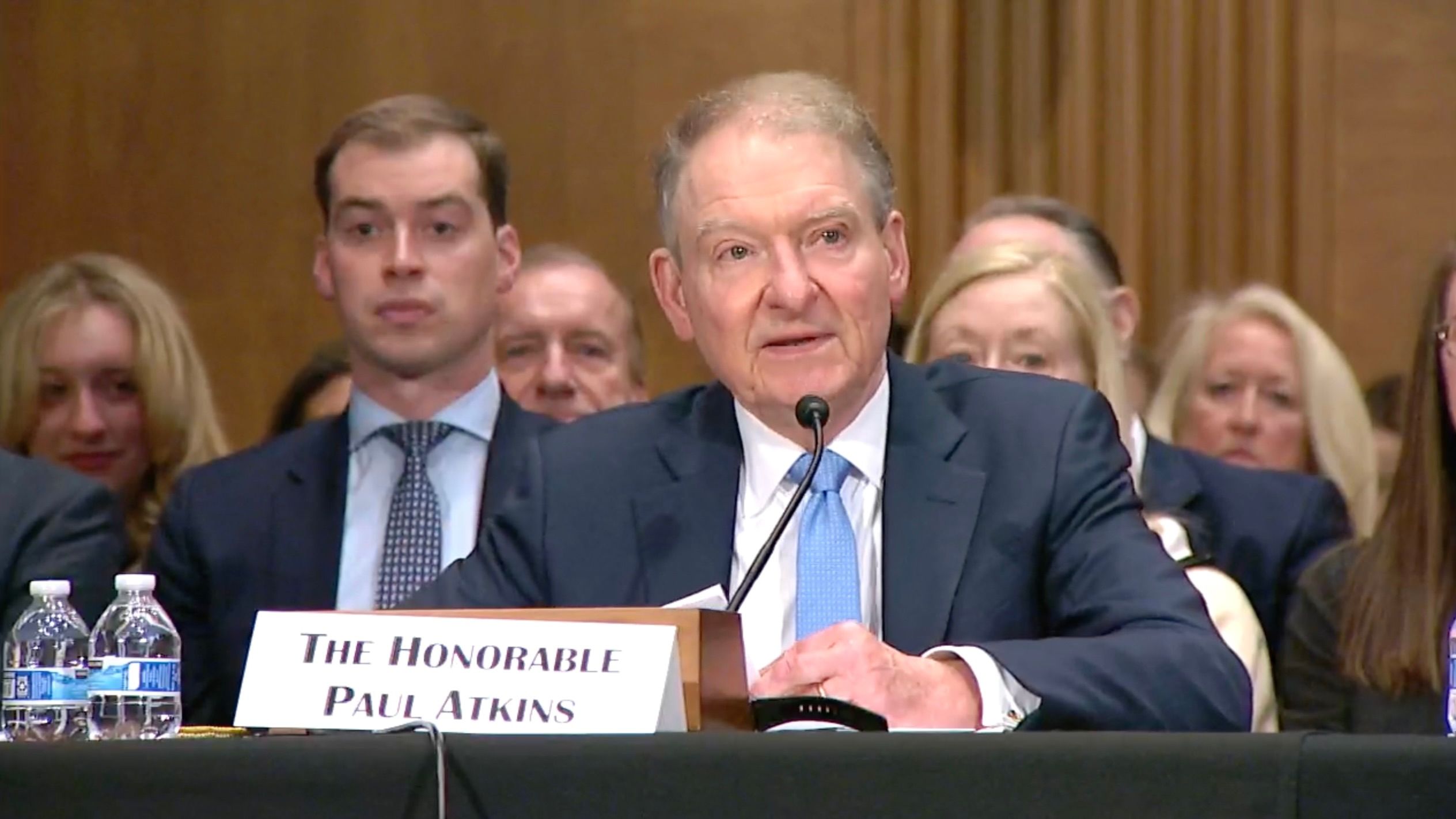

Now iFLYTEK shows off its Spark large language model as an alternative to ChatGPT or China’s own DeepSeek, which was developed in Hangzhou in neighboring Zhejiang province. Spark comfortably answers questions and generates striking graphical presentations—at least on subjects deemed acceptable by Chinese authorities. Spark is showcased for visitors alongside an automatic test-grading machine of written papers to save time for teachers, and two-way screens that allow for real-time automatic translation. All are already in production and use around China.

Chen, iFLYTEK’s general manager of AI translation software, said the firm had cooperated with Chinese companies such as Huawei on chip development.

“Huawei’s chip is now the best in China, and it’s us that makes their chip workable for large language models,” she said. “It takes us…more than quite a few months to make that work.” Huawei did not respond to a request for comment.

Even after exports on some Nvidia chips were eased by Washington, it’s now China that’s now restricting them—because it has its homegrown alternatives. Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang was quoted by media this week saying China is just “nanoseconds” behind the United States on chips and that export curbs should be lifted.

Navigating U.S. Restrictions

Most Chinese companies who spoke during the government tour were reluctant to go into detail on the impact of the U.S. restrictions, but those who did said they were finding their ways around.

“It’s not difficult for China,” Yuru Yang of Donghai Laboratory, which develops marine surveillance equipment including with military applications, told Newsweek.

Allen Ni of Tencent, whose WeChat messaging, social media and payment app alone has more than a billion users, said: “With our own self-developed technology and others, we will make sure that it won’t affect our development in AI.”

AI development is now an important focus in the Yangtze Delta, a cradle of China’s more than 4,000-year-old civilization that is held up as a prime example of China’s technological advances.

At a banquet on select delicacies of Anhui cuisine—renowned for the unique flavors of its wild local ingredients—Qin Junfeng, director-general of the Anhui Foreign Affairs Office, rattled off the latest impressive digital development statistics to a couple of dozen guests around the giant table. Toasts were drunk, although notably with orange juice given President Xi Jinping’s crackdown on excessive official consumption at the sort of functions that were once lubricated with plentiful bai jiu spirit.

The Communist Party’s attention to growing digital businesses was underlined by Wang Dongming, vice chairman of the Standing Committee of China’s National People’s Congress, at the opening of the Global Digital Trade Expo in Hangzhou: with the exhortation that it supported Xi’s vision of “global security, global civilization, and global governance,” with China “on the right side of history.”

At the expo, makers of humanoid robots lined up with electric vehicle companies, AI companies, the latest gaming apps and an automated lavatory attendant, among other devices.

State Backing

China’s high-tech push, however, also draws attention to a state industrial policy that critics say is used to give some firms an unfair advantage, both locally and internationally, and that can prove wasteful. A white paper from the International Monetary Fund in August put the equivalent fiscal cost of industrial policy through cash subsidies, tax benefits, subsidized credit, and subsidized land for favored sectors—including both private and state firms—at about 4 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), much more than in other countries.

It found tech companies were among the most favored.

“Many companies that are kind of incorporated as private in fact may be much less private than they seem,” said Magnus, the Oxford researcher. “They benefit enormously from the biggest transfer of wealth to industry that I think the world has ever seen.”

Chinese companies also reap the rewards of strong infrastructure investment. Officials in coastal Jiangsu province proudly showed off the Changtai Yangtze River Bridge, which had opened just weeks earlier with the longest span of any cable-stayed bridge in the world at nearly 4,000 feet.

Downstream at the Shanghai Hongqiaio International Central Business District, representative Frank Kong underlined the goal of the human part of the equation. China wants not only to attract returning Chinese engineers and keep the ones it has, but also to import talent from other countries—at a time that the United States has just hiked the fee for the H-1B visa used by tech companies to $100,000. From October 1, China is rolling out its own “K visa” precisely to bring in top science and technology workers from abroad.

“Technology is ultimately people and teams. The U.S. should hold on to talent rather than drive engineers out through immigration raids,” Dan Wang, author of the recent book Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future, wrote on X.

While challenges for those working in China include everything from the language to officialdom—and its visas do not provide a path to citizenship—lifestyles can be comfortable. Although not typical of most of China, Shanghai’s annual per capita GDP of over $30,000 is not far short of that in Japan.

However, the overall impact of high-tech industries for China should not be overstated, said Magnus. Some 80-85 percent of the economy does not consist of modern manufacturing and may not be faring nearly so well, he said.

“It’s very easy to be wowed by all of these incredible achievements and accomplishments which Chinese manufacturing has demonstrated and may yet demonstrate in the future. It’s also quite important to put it in perspective,” he said.

The technology does not always perform to order. One company developing pilotless electric air taxis had to cancel its planned display and instead showed off the aircraft in their hangar because it was raining.

Global Challenge

But the challenge posed to global competitors by the rapid growth of China’s tech sector is evident across the region.

No Chinese tech company showroom is complete without a giant glowing map of the latest app downloads, cars charged, or gigawatts of solar power generated in real time. It is as essential as a wall covered with patent certificates and awards from industry and government.

For some companies, the maps focus on China; for others, they are global. But only a handful indicate a presence in the United States. Uncertainties over tariffs under Trump have proved a discouragement for many as they look to alternative markets in Asia, Europe and the Global South.

High-end electric vehicle maker NIO, which has set up a battery swapping system as a three-minute alternative to recharging stops, said it had no U.S. plans for now as it adds another 20 countries for exports this year to the European markets it already serves, with largely automated production lines set to produce up to 350,000 vehicles in 2025.

It was a similar picture at China Aviation Lithium Battery, or CALB Group, one of the world’s top suppliers of batteries for electric vehicles, in Changzhou, Jiangsu province.

“We currently make our focus on Europe mostly,” said sales manager Ryan Xuan. “You know, the policy of America is not stable.”