Vast source of rare Earth metal niobium was dragged to the surface when a supercontinent tore apart

By Sophie Berdugo

Copyright livescience

Skip to main content

Close main menu

Live Science

Sign up to our newsletter

View Profile

Search Live Science

Planet Earth

Archaeology

Physics & Math

Human Behavior

Science news

Life’s Little Mysteries

Science quizzes

Newsletters

Story archive

CDC changes measles vaccine guidance

Skyscraper-sized asteroid flyby

Mysterious hand positions on Maya alter

It’s too late to stop AI, readers say

Anthropologist Ella Al-Shamahi on human origins

Don’t miss these

Lake Superior rocks reveal build up to giant collision that formed supercontinent Rodinia

World’s oldest rocks could shed light on how life emerged on Earth — and potentially beyond

400-mile-long chain of fossilized volcanoes discovered beneath China

Hot blob beneath Appalachians formed when Greenland split from North America — and it’s heading to New York

Study raises major questions about Earth’s ‘oldest’ impact crater

Planet Earth

‘Pulsing, like a heartbeat’: Rhythmic mantle plume rising beneath Ethiopia is creating a new ocean

There’s a ‘ghost’ plume lurking beneath the Middle East — and it might explain how India wound up where it is today

Enormous blobs deep beneath Earth’s surface appear to drive giant volcanic eruptions

Planet Earth

Scientists discover that mysterious giant structures beneath the North Sea seemingly defy what we know about geology

Scientists discover long-lost giant rivers that flowed across Antarctica up to 80 million years ago

Archaeology

We know humans arose in Africa, but archaeology is only just uncovering secrets of the continent’s early civilizations

Mercury’s ‘missing’ meteorites may have finally been found on Earth

Archaeology

2,200-year-old Celtic settlement discovered in Czech Republic — and it’s awash in gold and silver coins

Giant meteor impact may have triggered massive Grand Canyon landslide 56,000 years ago

Largest known Martian meteorite on Earth sells for $5.3 million at auction

Planet Earth

Vast source of rare Earth metal niobium was dragged to the surface when a supercontinent tore apart

Sophie Berdugo

19 September 2025

Potentially the largest known source of niobium discovered in central Australia formed 830 million years ago, and we can thank the breakup of the ancient supercontinent Rodinia.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

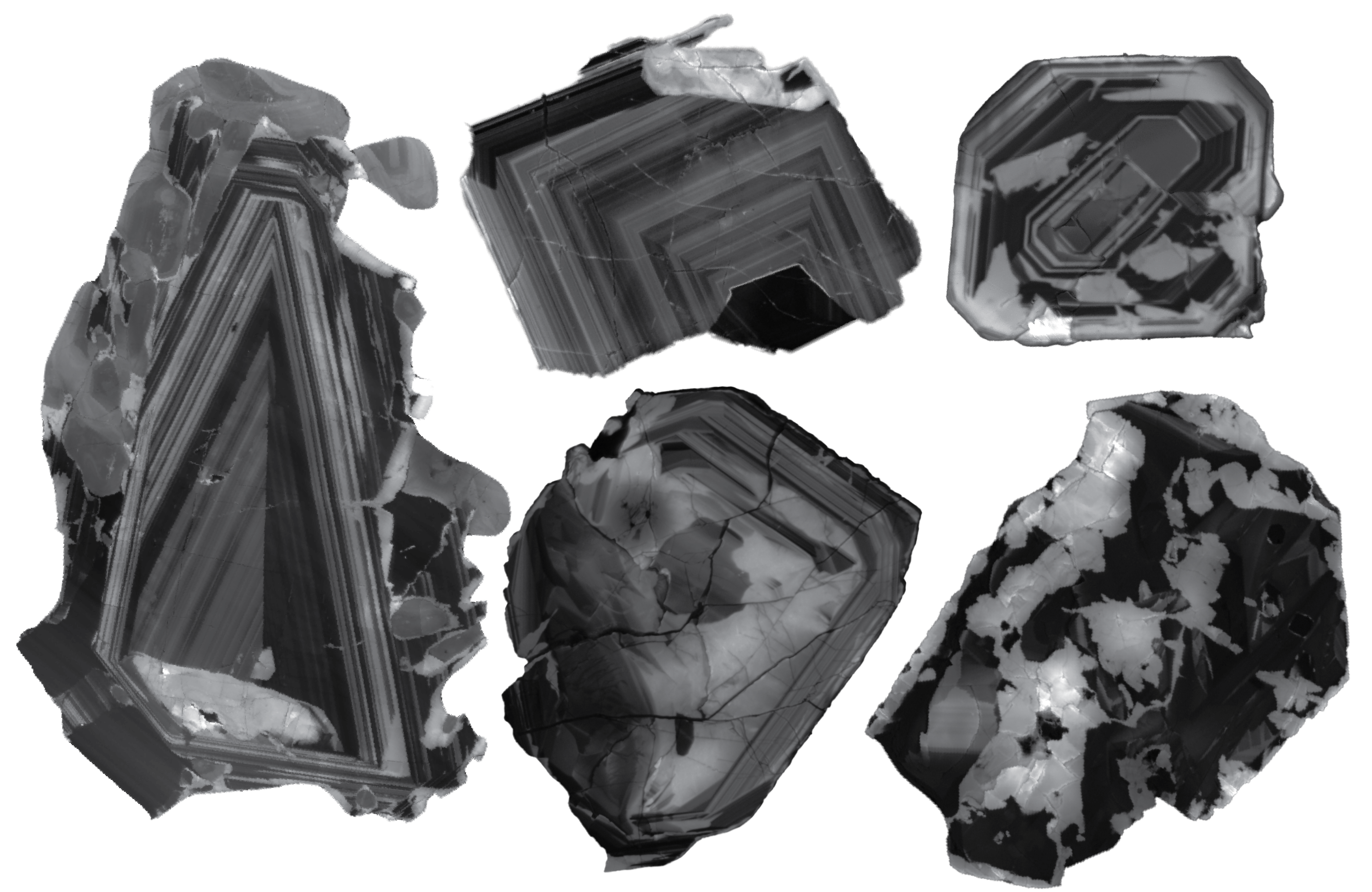

Zircon crystals ranging from 0.1 to 1 mm that were analyzed in this study. Their isotopic signatures allowed the scientists to determine the age of carbonatite formation with high precision.

(Image credit: Figure reproduced from: Droellner et al., (2025) Geological Magazine, Volume 162 , e33. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756825100204. © The Author(s), 2025. Published by Cambridge University Press. Licensed under CC BY)

A recently discovered enormous source of niobium — a metal that’s essential for much of today’s technology — appears to have formed when the supercontinent Rodinia ripped apart around 830 million years ago, according to a new study.

The niobium-rich carbonatites, which could be one of the world’s largest sources of the metal, have come from deep within the Earth’s mantle, scientists reported in a study published Sept. 2 in the journal Geological Magazine.

Niobium is a silvery, corrosion-resistant metal with superconducting properties, making it key for strengthening steel and for use in devices such as MRI scanners and particle accelerators.

You may like

Lake Superior rocks reveal build up to giant collision that formed supercontinent Rodinia

World’s oldest rocks could shed light on how life emerged on Earth — and potentially beyond

400-mile-long chain of fossilized volcanoes discovered beneath China

Currently, 90% of the global supply of niobium is extracted from a single mine in Brazil, with the other 10% coming from a Canadian mine. Understanding how, where and when these massive Australian sources formed can help to find new deposits, study co-author Maximilian Dröllner, a sedimentology researcher at the University of Göttingen in Germany, told Live Science.

Although small amounts of niobium can be found encased in various types of rock, the quantities required for economic and industrial extraction are primarily sourced from carbonatites — crystalline rocks that consist mainly of magmatic carbonate.

Carbonatites are “a bit like a treasure box,” Dröllner said, because they harbor important metal resources and rare earth elements encased within minerals, Their exact compositions vary depending on where the magma originated inside Earth.

Related: What is the rarest mineral on Earth?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Contact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.

Carbonatites are generally only found beneath Earth’s surface. But because the surface doesn’t reveal what’s buried deep below, exploratory drilling and core extraction are the only ways to know for sure.

The two new niobium-rich deposits in Australia’s Aileron Province — called Luni and Crean — were unearthed during such campaigns by the mining companies WA1 Resources Ltd. in 2022 and Encounter Resources in 2023. The Luni deposit has an estimated 200 million metric tons of niobium, and the smaller Crean deposit has around 3.5 million metric tons.

The companies used diamond core drills to extract long, cylindrical sections of material from each site. Dröllner and his team then took eight samples from three Luni drill cores and two samples from a single Crean drill core.

You may like

Lake Superior rocks reveal build up to giant collision that formed supercontinent Rodinia

World’s oldest rocks could shed light on how life emerged on Earth — and potentially beyond

400-mile-long chain of fossilized volcanoes discovered beneath China

They took a thin slice of each sample from the areas that appeared to have the most diverse mixes of minerals and textures, which allowed the researchers to tap into the geological story of the rock.

Then, they used a Selfrag machine to fire a series of lightning bolts at the remaining chunks. This caused the rocks to shatter along the boundaries of each mineral grain. Next, they placed these grains under a microscope and a mass spectrometer to get an age for rocks.

A close-up view of pyrochlore crystals (black) — the main mineral host of niobium — surrounded by apatite (pale gray) from the Luni carbonatite mineral map. The intricate zoning patterns inside the apatite act as a geological “time capsule”. (Image credit: Figure reproduced from: Droellner et al., (2025) Geological Magazine, Volume 162 , e33. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756825100204. © The Author(s), 2025. Published by Cambridge University Press. Licensed under CC BY)

By looking at the ratio of different isotopes with their decay products, the research, which was partially funded by the mining companies involved, found that the carbonatites, including the niobium mineralization, formed around 830 million to 820 million years ago.

The analysis also revealed a “clear mantle fingerprint,” Dröllner said, which indicates that the carbonatite magma came from Earth’s mantle rather than from the crust. Both deposits seem to have come from the same source, with a fork in the pipe of the internal plumbing system channeling the magma to each spot.

RELATED STORIES

—Enormous deposit of rare earth elements discovered in heart of ancient Norwegian volcano

—China discovers never-before-seen ore containing a highly valuable rare earth element

—Volcano in Tanzania with weirdest, runniest magma on Earth is sinking into the ground

The team linked the rupture of the supercontinent Rodinia to these deposits. When the supercontinent was pulled apart by the movement of the tectonic plates, Earth’s crust thinned at the newly formed junctures, granting the planet’s innards easier access to the surface. An analysis of helium isotopes showed that the Luni deposit was within touching distance of the surface around 250 million years ago.

Anthony E. Williams-Jones, a professor of geology and geochemistry at McGill University in Montreal who was not involved in the study, said this is very high-quality research. However, he noted that because the researchers only examined drill cores, there is no information on the extent of the deposits and what they look like over the whole area.

Dröllner said more research is needed to construct a three-dimensional map of the deposits, which will eventually allow this niobium to be extracted. Nonetheless, this new understanding of how the Luni and Crean niobium deposit formed will help to create a checklist for identifying likely other spots rich in the metal, he added.

Sophie Berdugo

Social Links Navigation

Live Science Contributor

Sophie is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She covers a wide range of topics, having previously reported on research spanning from bonobo communication to the first water in the universe. Her work has also appeared in outlets including New Scientist, The Observer and BBC Wildlife, and she was shortlisted for the Association of British Science Writers’ 2025 “Newcomer of the Year” award for her freelance work at New Scientist. Before becoming a science journalist, she completed a doctorate in evolutionary anthropology from the University of Oxford, where she spent four years looking at why some chimps are better at using tools than others.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Lake Superior rocks reveal build up to giant collision that formed supercontinent Rodinia

World’s oldest rocks could shed light on how life emerged on Earth — and potentially beyond

400-mile-long chain of fossilized volcanoes discovered beneath China

Hot blob beneath Appalachians formed when Greenland split from North America — and it’s heading to New York

Study raises major questions about Earth’s ‘oldest’ impact crater

‘Pulsing, like a heartbeat’: Rhythmic mantle plume rising beneath Ethiopia is creating a new ocean

Latest in Geology

Narusawa Ice Cave: The lava tube brimming with 10-foot-high ice pillars at the base of Mount Fuji

Giant sandy ‘slug’ crawls through floodplains in Kazakhstan, but it could soon be frozen in place

The geology that holds up the Himalayas is not what we thought, scientists discover

Loughareema: The ‘vanishing lake’ in Northern Ireland that mysteriously drains and refills itself within hours

Lake Superior rocks reveal build up to giant collision that formed supercontinent Rodinia

Three Whale Rock: Thailand’s 75-million-year-old stone leviathans that look like they’re floating in a sea of trees

Latest in News

Vast source of rare Earth metal niobium was dragged to the surface when a supercontinent tore apart

Skywatching alert! See 2 bright comets on the same night as a meteor shower this October

Saturn will be at its biggest and brightest on Sept. 21 — here’s how to see it

First-ever black hole to be directly imaged has changed ‘dramatically’ in just 4 years, new study finds

CDC committee votes to change measles vaccine guidance for young children

Farewell to the computer mouse? Bizarre new designs could reduce wrist injuries, scientists say.

LATEST ARTICLES

Farewell to the computer mouse? Bizarre new designs could reduce wrist injuries, scientists say.

Saturn will be at its biggest and brightest on Sept. 21 — here’s how to see it

Skywatching alert! See 2 bright comets on the same night as a meteor shower this October

CDC committee votes to change measles vaccine guidance for young children

First-ever black hole to be directly imaged has changed ‘dramatically’ in just 4 years, new study finds

Live Science is part of Future US Inc, an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate site.

Contact Future’s experts

Terms and conditions

Privacy policy

Cookies policy

Accessibility Statement

Advertise with us

Web notifications

Editorial standards

How to pitch a story to us

Future US, Inc. Full 7th Floor, 130 West 42nd Street,

Please login or signup to comment

Please wait…