By Aaron Gell,Josh Ritchie For

Copyright newrepublic

Despite the dearth of raised hands in that March committee hearing, launching an insurance startup in Florida has become a highly attractive proposition. For one thing, you don’t need to pass the rigid economic stress tests and other financial evaluations administered by trusted ratings agencies like S&P or AM Best. Demotech, a ratings company with considerably looser standards, has become the new industry leader, with nearly 60 percent of the Florida market. According to a 2024 academic study, insurers rated by Demotech were nearly 25 times more likely to go insolvent than those rated by a more established competitor.

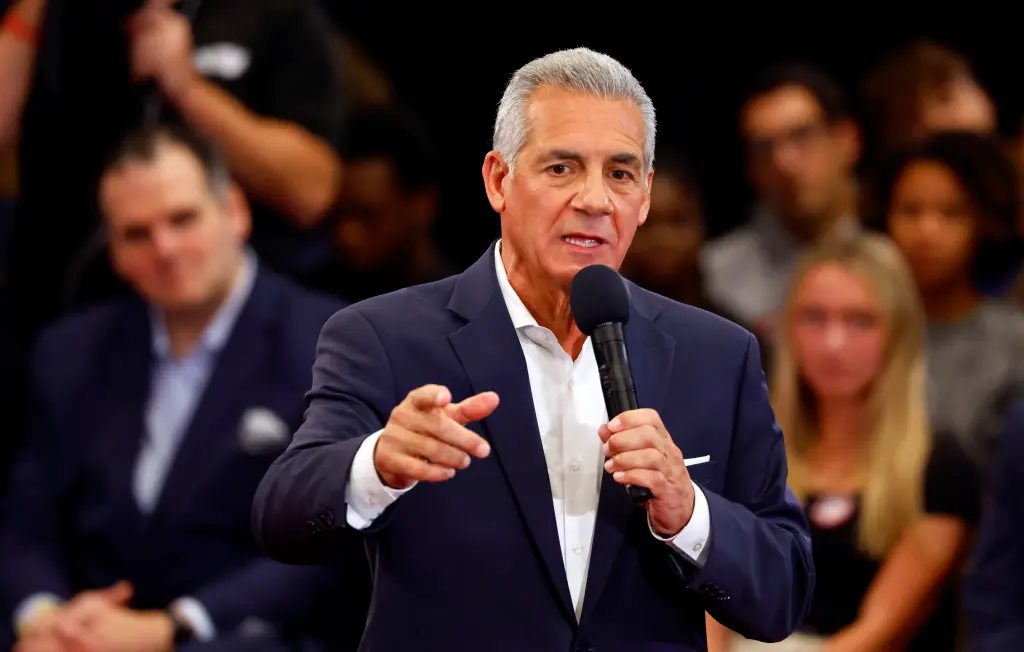

Meanwhile, you won’t need to hire a sales team, since under the takeout program, the state of Florida will simply hand you a stack of paying customers from its massive Citizens stockpile and let you choose the least risky among them. Policyholders have no choice in the matter. As Bruce Lucas, the CEO of one of Florida’s biggest insurance startups, Slide, put it in a 2022 podcast interview, “You send out these notices, and it gets mixed in with everybody’s junk mail in the trash can. And next thing you know, you’ve got 200,000 customers.” And should you want to pocket a bit more money, you might consider fraudulently altering field reports by third-party adjusters—an accusation leveled by several whistleblowers in 2024. (Heritage Insurance, which Lucas ran until 2020, is among the carriers alleged to have edited adjuster reports as a way of lowering claims; it recently filed a libel suit against one of the adjusters who appeared in a 60 Minutes segment about the allegations.)

When these smaller insurers go out of business, as they regularly do—often after handsomely compensating their officers and shareholders and letting affiliates bank the profits—consumers are shuffled back to Citizens, and the cycle continues. It will come as little surprise that, according to The Washington Post, Lucas and his companies have given millions to Florida Republicans, including $350,000 to the state’s former CFO and freshly minted U.S. representative, Jimmy Patronis. (Also, fun fact: Lucas previously did legal work for Enron.)

Politics aside, property insurers have long understood that the climate is changing. It’s their business to know. And if they don’t, the reinsurers—well-capitalized multinationals, usually based in tax havens like Bermuda, that indemnify insurance companies against major catastrophes—are happy to explain. (While insurers’ rates are often capped by state officials, reinsurers charge what they like.) Indeed, it’s hard to think of another sector of the economy that is better attuned to the cascade of disasters the oil and gas industry has virtually guaranteed by mindlessly pumping ever more CO2 into the atmosphere.

And yet, it turns out that some of these same insurers are actively making the problem worse. Many invest their “float” in major oil producers, and underwrite fossil fuel development projects that couldn’t happen at all without insurance. “By underwriting and investing in new and expanded fossil fuel projects,” Whitehouse said in a press release announcing a 2023 investigation, “U.S. insurers are helping Big Oil bring us closer to the worst runaway climate scenarios, which threaten lives, livelihoods, and the federal budget.” In 2023, Allianz announced it would cease underwriting or funding such projects in line with commitments made with the Net-Zero Insurance Alliance, a group of insurers convened by the U.N. to address climate change issues. A month later, after 23 right-wing U.S. attorneys general challenged the alliance on antitrust grounds, it was disbanded. (A new group, the Forum for Insurance Transition to Net Zero, launched in the interim.)

Remarkably, most major carriers still support fossil fuel production, knowing full well that their actions will hasten the demise of their own industry and so much else. Kousky thinks there’s “a collective action problem” at work. “Like, if one insurer gives up that profitable business, then that fossil fuel company will go to the insurer who doesn’t care,” she explained. “Unless you can somehow get all of the companies to agree to withhold insurance and all the banks to withhold financing, which is just a really difficult problem when you can make a ton of money off it,” she added, “it’s not going to happen.”

One wonders what Ben Franklin, who spent his life working to mitigate fire risk (and not only for policyholders of the Philadelphia Contributionship), would make of this brazen stampede toward oblivion in pursuit of profit. A hint might be found in the story of his “Pennsylvanian Fire-Place,” now better known as the Franklin Stove. According to Bainbridge, when the governor of Pennsylvania offered him a patent on the invention, Franklin declined, noting, “As we enjoy great advantages from the inventions of others, we should be glad of the opportunity to serve others by any invention of ours, and this we should do freely and generously.”

One day in August 1914, as the Great War threatened to envelop Europe, the American philosopher Josiah Royce delivered a lecture at Berkeley’s Philosophical Union outlining a bold scheme by which the nations of the world might usher in a new era of peace and mutual respect. Insurance, he thought, could save the world.

In his address, Royce framed the “insurance principle” as a powerful tool of social relations. “It discourages recklessness and gambling,” he claimed. “It contributes to the sense of stability.”

His proposal called for the establishment of a global mutual insurance pool, funded by participating nations and overseen by an international board of trustees, that would indemnify member states against catastrophe, pestilence, and, ultimately, war.

Royce’s idealism can sound almost farcical a century later, when the spirit of mutual aid at the core of insurance has been so thoroughly vanquished by the imperatives of capital. But as the world stumbles toward a global crisis sure to make the shell shock and mustard gas of World War I look mild in comparison, Royce’s framework may begin to sound more practical.

The calamities and costs of an overheating planet will touch every corner of the globe, albeit unequally. It’s not hard to imagine an updated Roycean scheme designed not only to provide compensation for those most harmed but also to subject wealthy, Western nations to the heftiest premiums. A sizable tax on carbon emissions could provide further funding.

There is an appealing measure of justice in forcing climate criminals to compensate their victims, but the real genius of the insurance framework, as Royce saw, is the way it tends to focus attention on the mitigation of risk. “In its efforts not only to alleviate but to prevent pestilence and famine,” he predicted, “the board of trustees … would inspire all the nations actually to work together … in a charitable and in a businesslike way, as they have never worked before.” It would engender “a fecundity, an ingenuity, and a wisdom of which we shall know nothing until we … teach the nations, by the potent devices of mutual insurance, the art of loyalty to the community of mankind.”

The notion that capitalism might yet save us from the nightmare that the system itself has wrought is probably a stretch. Royce died in 1916, well before McKinsey taught Allstate to put on its “boxing gloves.” But it is, at least, an idea, a starting point, and we will soon need all the ingenuity and wisdom we can muster.

When Suzi Bahan told me, as we sat in her government-supplied trailer surrounded by cases of beer and hard seltzer, that she hadn’t done enough research to have an opinion on climate change, we’d already finished the formal interview. My notebook and phone were stowed in my pockets, and, if I’m being honest, I was a few tequilas in.

“Fair enough,” I said, “but I have done a shitload of research.” I told her to think of me not as a reporter but as a friendly blowhard who likes to read and has talked to a lot of experts. “There’s a very good chance that, 10 years from now, this entire island will be underwater,” I predicted. “The place might not even exist.” She took this better than I expected, so I pressed on, suggesting she forget about rebuilding, forget the permitting delays and the ever-increasing material costs, forget the tiki bar, and move on with a new life, in a new, relatively safer location. Maybe not on a barrier island.

“Take whatever you can squeeze out of your insurance company, sell to whatever big chain wants it,” I said, “and seriously, Suzi, just get the fuck out.”

She took this in for a second. “You think so?” she asked. I nodded. “I really hope I’m wrong,” I told her. “And if I am, great. You can come back and visit anytime.”