By Oluwole Crowther

Copyright businessday

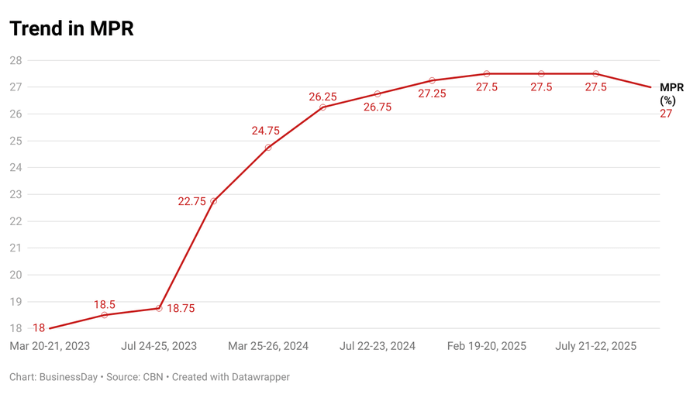

Nigeria’s central bank trimmed its key rate by 50 basis points to 27 percent in September, the first cut under Governor Cardoso. But fresh liquidity rules tempered optimism, showing the MPC’s cautious balance between growth and discipline.

With headline inflation easing to 20.12 percent in August, its fifth straight decline, the policy shift gained some room.

Mixed signals in policy stance

Alongside the rate cut, the standing facilities corridor was narrowed to ±250 basis points. This means banks can now borrow from the CBN at 29.5 percent instead of 32.5 percent, while returns on excess deposits were cut to 24.5 percent. “In a way, this is actually more influential than the 50 basis points cut,” Hakeem Muhammed, Executive Director, Global Markets & Institutional Banking at FSDH, noted on Channels TV, arguing that it will push banks to lend rather than park idle cash with the apex bank.

The bigger surprise was the new 75 percent Cash Reserve Requirement (CRR) on non-TSA public sector deposits, which analysts say fundamentally changes the calculus for banks holding government-related funds. “If you take N1 billion, you now have to surrender N750 million to the central bank at zero interest. Meanwhile, the depositor still sees the full balance in their account. That’s a game changer,” said another market watcher, Tajudeen Ibrahim, Director of Research & Strategy at Chapelhill Denham.

By contrast, the CRR for commercial banks was cut from 50 to 45 percent, easing conditions for private sector lending. Analysts described the move as both dovish and hawkish, supporting credit creation while tightening liquidity on public deposits to promote transparency.

Taken together, the measures send conflicting signals: easier credit for the private sector but tighter controls on public funds, leaving investors and analysts to weigh how these crosscurrents will shape the markets.

Read also: CBN’s rate cut opens window for business growth, expansion

Market implications

For the fixed income market, the rate cut is expected to lower the CBN’s cost of OMO issuances. But with more than N4 trillion in securities and coupon payments maturing in November and December, liquidity management will be crucial. “There’s about N2.1 trillion liquidity in the market today that the central bank has not mopped up for a while,” Hakeem noted. “What they do post-MPC will be critical.”

In equities, lower rates are expected to lift valuations by reducing the weighted average cost of capital. “It means we should be buying more equities going forward,” Tajudeen remarked. The picture is less favourable for banks, however. “Banks thrive more in a high-interest-rate environment. Now they have to think out of the box to see how much more money they can make elsewhere apart from interest income.” Tajudeen added.

Foreign investors may also reassess Nigeria’s relative appeal. With the US Federal Reserve trimming its benchmark by 25 basis points, Nigeria’s yield differential has narrowed. “On an overall basis, if you are a US investor, your interest advantage is lower by 25 basis points by what has just been done,” Hakeem warned.

The MPC’s decision marks its first rate cut after a string of hikes under Governor Olayemi Cardoso. By combining a modest easing of credit conditions with a punitive rule on public deposits, the CBN is signalling that growth support will not come at the expense of stability. Businesses may cheer the prospect of cheaper loans, but as analysts agree, the real test will be how the central bank manages the liquidity surge due before year-end.