By Lillian Perlmutter • Times of San Diego

Copyright timesofsandiego

For the three immigrants in the waiting room at the Immigration and Customs Enforcement office, a moment of truth was approaching. The trio — a woman in her fifties from Tijuana, a Guatemalan man in his forties, and a 20-year-old woman seeking asylum from Peru — sat in silence, waiting to see which surveillance device they would be forced to wear.

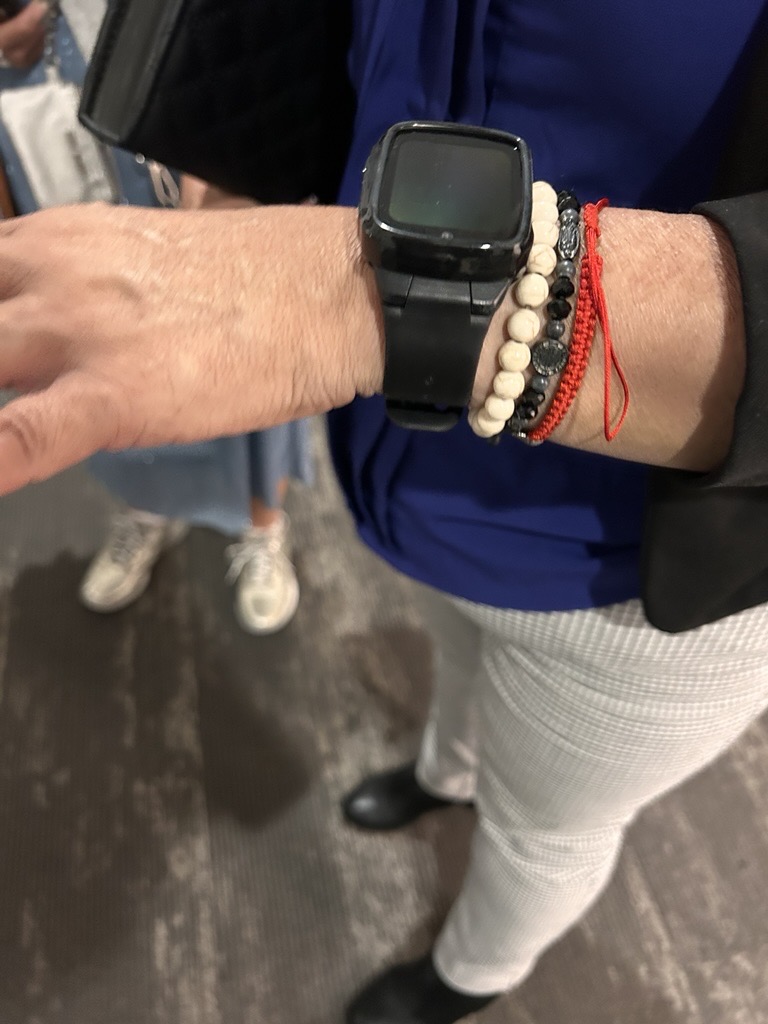

Their fate could go one of two ways: ankle monitor or smart watch. Whichever accessory they received, they would not be able to take it off, even to shower, for months on end. Everyone preferred the more discreet wristwatch, as the ankle monitor gives an implication of criminality, but the agents behind the glass would make that decision.

For the past few weeks, lawyers and observers at the San Diego immigration court say ICE agents have stopped detaining immigrants in the hallways, rerouting them instead into a program called Intensive Supervision Appearance. The immigrants, who are awaiting deportation hearings, applying for asylum, or attempting to change their status with the government, are given ankle monitors or smartwatches that track their every move until they return to the court months later for their next scheduled appearance.

The monitors are just one part of the expansion of a longstanding deal between the Department of Homeland Security and a company called BI Inc., which makes the devices and is paid to track the people wearing them.

DHS and BI Inc. did not respond to repeated requests to answer questions about the surveillance program, including why and how much the use of the devices has increased in San Diego.

Immigrants say the devices interfere with their lives, costing them time, money, and dignity.

As she left her deportation hearing at the San Diego immigration court on September 17, Aidia, an immigrant from Mexico who has lived undocumented in the US for 23 years, was cornered in the hallway. Two ICE agents wearing black, one with his face covered, handed her a letter ordering her to go to their office and pick up a surveillance device.

Aidia, and all of the undocumented immigrants interviewed by the Times of San Diego, asked to be identified by only their first names, to prevent further targeting by the Department of Homeland Security.

After the encounter with the ICE officers, Aidia’s lawyer said she was “lucky” because if she had been in that hallway the previous month, she would have been arrested and held at the Otay Mesa detention facility for anywhere from days to months. Now, as part of the surveillance program, she would be able to go free — though accompanied, of course, by the Department of Homeland Security. It would be watching her every step until her next hearing in January.

Multi-billion-dollar contract for monitors

BI Inc., a subsidiary of the private prison giant Geo Group, provides the surveillance devices to ICE through a $2.2 billion contract signed in 2020 and extended this year. The ankle monitors and smart watches use GPS, wifi, and satellite technology to track their wearers, while a partnership with Google provides the case managers from BI Inc. with real-time Google Maps data showing where the immigrants are. According to internal ICE data, more than 180,000 people were currently enrolled in an Alternatives to Detention program nationwide as of Sept. 6, and more than 29,000 of them were wearing ankle monitors.

An internal DHS memo in June encouraged ICE personnel to increase the use of ankle monitors, putting them on immigrants “whenever possible.” But observers at the San Diego immigration court didn’t notice this change in policy until September.

“They’re putting them on everyone except unaccompanied minors,” immigration lawyer Pedro de Lara said, as a pregnant woman sidestepped to fit her bump through the ICE office doorway.

Under previous administrations, de Lara explains, most of these people would not have been arrested or monitored by ICE. Since White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller instituted an informal quota of 3,000 arrests per day in May, ICE has begun picking up people outside immigration court hearings who are following the law, attempting to change their immigration status through the available legal pathways.

Since President Donald Trump’s inauguration, the majority of people arrested by ICE in the San Diego area have had no criminal record.

The nearby Otay Mesa detention facility has been operating over capacity for much of 2025, according to detention data and reports from lawyers visiting the prison. Lawyers including De Lara say the immigrants detained there have been denied medical care and some are sleeping on the floor. In recent weeks, COVID began spreading through the prison.

The cost of a surveillance device, $4.20 per day per apparatus, is much lighter on ICE’s pockets, as detaining an inmate in a facility has an average cost of $152 a day, according to the agency.

In recent weeks, DHS has also begun opening up non-urgent cases that were previously put aside.

Aidia had a deportation order because she was apprehended at a traffic stop in 2011 and found to be living in the country on an expired visa— the case was abandoned for over a decade and then reopened without explanation this month. ICE did not respond to a request to comment on why it is reopening old cases.

A time- and money-consuming process

Immigrants who are given the ankle monitors and wristwatches say they often need to take time off work on short notice, because the device needs to be switched out on a weekly basis. Instead of scheduled appointments, though, case officers will call and summon immigrants often just hours in advance. Ramón, an immigrant from Mexico who has been wearing an ankle monitor for the past four months, says one time, an officer “called at 1 a.m.” and told him to come into the office the next day. Ramón says he has lost $2,000 between missing work and Uber rides to the weekly appointments. Internal ICE data suggests Ramón’s experience is on the lighter side— the average amount of time people wear the ankle monitor in many locations is over a year.

Martín, an immigrant from Guatemala who is a construction worker, worried if he received an ankle monitor instead of a wristwatch, he would lose his job entirely, because he would not be able to put on his work boots. The ankle monitor, which is four inches wide, was modeled on a design originally made for cattle.

Martín’s son, Alex, who is a US citizen in his early 20’s, accompanied Martín to the office, and said he was told by one of the agents that his father would have no opportunity to advocate for a wristwatch instead of an ankle monitor. “Basically, they’re saying we can’t do anything,” he said.

Aidia said when the case managers from BI Inc. showed a video preparing her for her new routine with the surveillance device, they said there will be days Aidia will not be allowed to leave the house and go to work, and she will not be given advanced notice. Aidia is a property manager, and her work requires her to oversee the maintenance of buildings in person. ICE agents will also show up at her home for check-ins, and sometimes, with a short, prior warning, the smart watch will take a photo of her face— the watch has biometric capabilities, allowing for facial recognition. This pattern will continue until her next court hearing in January.

“There’s nothing we as lawyers can do [to stop this],” De Lara said. “Because they [ICE] are allowed to do what they’re doing.”

After this time-consuming, money-draining process is completed and the device is removed, the Department of Homeland Security, BI Inc., and Google may still retain data on these immigrants’ movements, habits, and the locations of their homes and workplaces. Both BI and DHS did not respond to repeated requests for information on how the devices work, who controls the camera, as well as the location monitors and the data they collect, and whether the information is used to track other people in proximity. Google did not immediately respond to questions about how they work with the program.

In 2022, a group of 25 Democratic lawmakers sent a letter to the Department of Homeland Security urging reform of the Intensive Supervision Appearance program, and alleging that the data from these wearable devices had been stored and used to conduct further ICE raids. They wrote that the devices cause “extreme physical and mental damage.” In a public statement, BI denied that their devices are unsafe and called the letter “politically motivated.” On their website, BI says that through the implementation of their surveillance technology, they are “strengthening communities.”

At her next court hearing, Aidia could still be detained and deported to Mexico, despite having lived in the US for decades. Aidia is the primary caregiver for her elderly mother, Oliva, who was waiting for her outside the ICE office. “They have to let her stay [in the US], because she has paid too much money to this country [in taxes],” Oliva said. “They have to let her stay, because what’s going to happen to me?”

When Aidia reappeared from her meeting with the BI case managers, she was accompanied by the wristwatch, which has a square, black screen, wider than her forearm. All the other immigrants, even Martín, who was worried about occupational hazards, walked out with bulky black boxes strapped to their ankles. There would be no way to appeal for a change, and no way to take them off.

Lillian Perlmutter covers immigration for Times of San Diego and NEWSWELL.