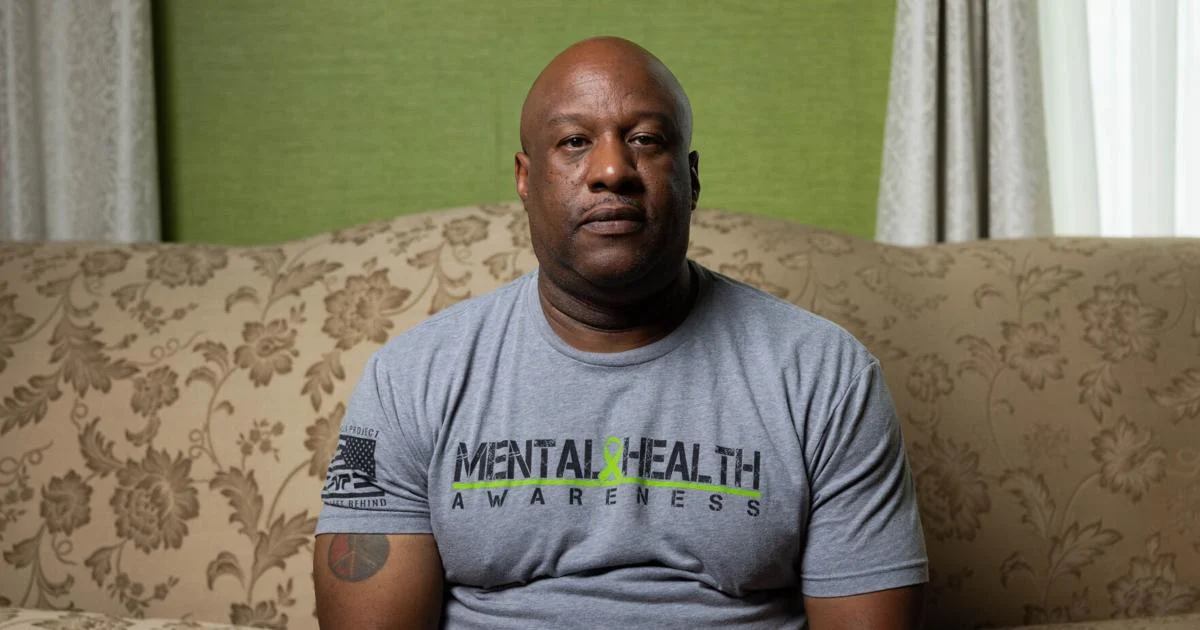

A Richmond firefighter is suing some of America’s biggest chemical companies, alleging their negligence contributed to his leukemia diagnosis.

Jonathan Clarke, a veteran master firefighter, is suing numerous companies involved in the making of firefighter “turnout” gear, which he’s worn for more than 20 years on the job.

The suit alleges that his leukemia diagnosis in 2022 was the result of chemicals woven into firefighting gear in order to make the garments waterproof. The science around the chemicals, known as PFAS, has recently clarified the picture around their potential link with cancer.

Clarke’s suit names 21 companies, including 3M, Chemours, Honeywell and another 18 associated with the production of PFAS or firefighter turnout gear. He’s one of several firefighters alleging harm from the gear in Virginia.

The suit alleges that the chemical makers and purveyors of turnout gear knew about the harms of PFAS but failed to relay the chemicals’ “toxic nature” to firefighters.

The Times-Dispatch reached out to 3M, Chemours, Honeywell and three other named makers of firefighting turnout gear. None returned requests for comment. Some companies, including Honeywell, have recently rolled out PFAS-free firefighter gear.

PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are a group of chemicals first created by chemists at DuPont in the 1930s. They are prized for their strong chemical bonds, which don’t break down naturally, and their water-resistant and flame-retardant properties. By dipping fabric into vats of PFAS chemicals, manufacturers were able to imbue both those qualities into firefighting turnout gear.

But a growing body of science has also tied PFAS to a series of worrying health risks, including developmental delays, immune dysfunction and links to several forms of cancer after prolonged exposure. As a result, federal regulators have imposed increasingly tighter limits on PFAS, particularly in American drinking water.

Firefighters first drew their attention to the chemicals in 2016, when the wife of a Massachusetts firefighter sought answers for her husband’s cancer diagnosis. She sent samples of turnout gear to a nuclear physicist at the University of Notre Dame.

That physicist, Graham F. Peaslee, used a technique called proton-induced gamma emission to measure the percentage of PFAS in a given sample of turnout clothing.

In 2020, Peaslee said his tests found approximately a pound of the chemicals in each full set of gear. His tests also found that PFAS shed from the clothing over time. The next year, further research found that even the dust in fire stations is heavy with the chemicals, suggesting a health risk even when firefighters are off-duty. In 2024, researchers in England found that the chemicals move through human skin.

The findings came after manufacturers said their products contained just “trace amounts” of PFAS, if any were used at all, according to a letter sent by manufacturer Lion to The Columbus Dispatch in 2017. In 2023, Lion issued a news release stating that neither Lion nor its textile suppliers intentionally adds PFAS to their turnout gear. Peaslee’s study showed levels of PFAS in Lion’s equipment that appear to counter that position.

“They all lied through their teeth,” Peaslee said in an interview with The Times-Dispatch. “They all said, ‘Nope, we don’t use them. And if we do, it’s just trace amounts.’”

Today, Lion says its turnout gear made since the end of 2021 does not contain PFAS, but acknowledges that gear produced earlier does contain a PFAS film.

Clarke’s suit alleges that he used the gear as intended for 20 years and was never told by manufacturers that it might be harmful to his health. He’s still a working firefighter, except now he takes chemotherapy drugs to treat his cancer. In 2022, the city of Richmond announced a blood drive in his honor.

Listen now and subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | RSS Feed | SoundStack | All Of Our Podcasts

Clarke is one of at least six firefighters in Virginia taking injury claims related to PFAS to court. He’s joined by two firefighters in Henrico County, Casey Barden and John Hudnall, who were also diagnosed with cancer, according to their lawyer, Kevin Biniazan.

Biniazan said he hopes to uncover what these companies knew, and when they knew it.

“Ultimately, with transparency, comes a path towards accountability for false promises, and for exposing him and his brothers and sisters to carcinogens without warning,” Biniazan said.

Bill Boger, a firefighter in Henrico and a representative of the Virginia Professional Fire Fighters union, said it’s the perceived lack of transparency that bothered firefighters the most.

“That is the one thing that we just can’t fathom. It’s that they knew it,” Boger said. “They knew it was in there, and they never let us know.”

Boger said that at one time, firefighters would perform demonstrations at local schools and offer to put kids in their firefighting gear.

“We don’t do that anymore,” said Boger. “We don’t want to take that risk.”

In 2023, the International Association of Fire Fighters sued the nonprofit group that sets the standards for turnout gear. The suit alleges that the standards effectively require the use of PFAS.

“The very gear designed to protect firefighters, to keep us safe, is killing us,” said Edward Kelly, the group’s president, who said the suit was “about finding justice for their brother and sister members.”

Since then, several states have banned PFAS in firefighter gear altogether. State legislatures in Connecticut and Massachusetts banned the sale of PFAS-containing turnout gear beyond 2028. According to The Guardian, those two bills were opposed by manufacturers.

Clarke’s own legal challenge may face a significant hurdle: proving that his leukemia diagnosis was strictly linked to PFAS in his gear rather than any other carcinogen. The profession of firefighting has long been linked to higher rates of cancer, with researchers classifying the profession itself in 2022 as carcinogenic.

That classification factors in the toxicity of their gear but also considers the toxicity of all the smoke inhaled at the scene of a burning building. Modern homes contain more plastics and chemicals, which are more harmful to inhale.

In his living room, Clarke said he’s not sure what he might have done differently. He loves his job, he said. And he still suits up in the same gear that he believes may be slowly killing him.

If they didn’t already know it, Clarke said most people would never guess he has cancer.