By Japan Today Editor,Soichiro Tanaka

Copyright japantoday

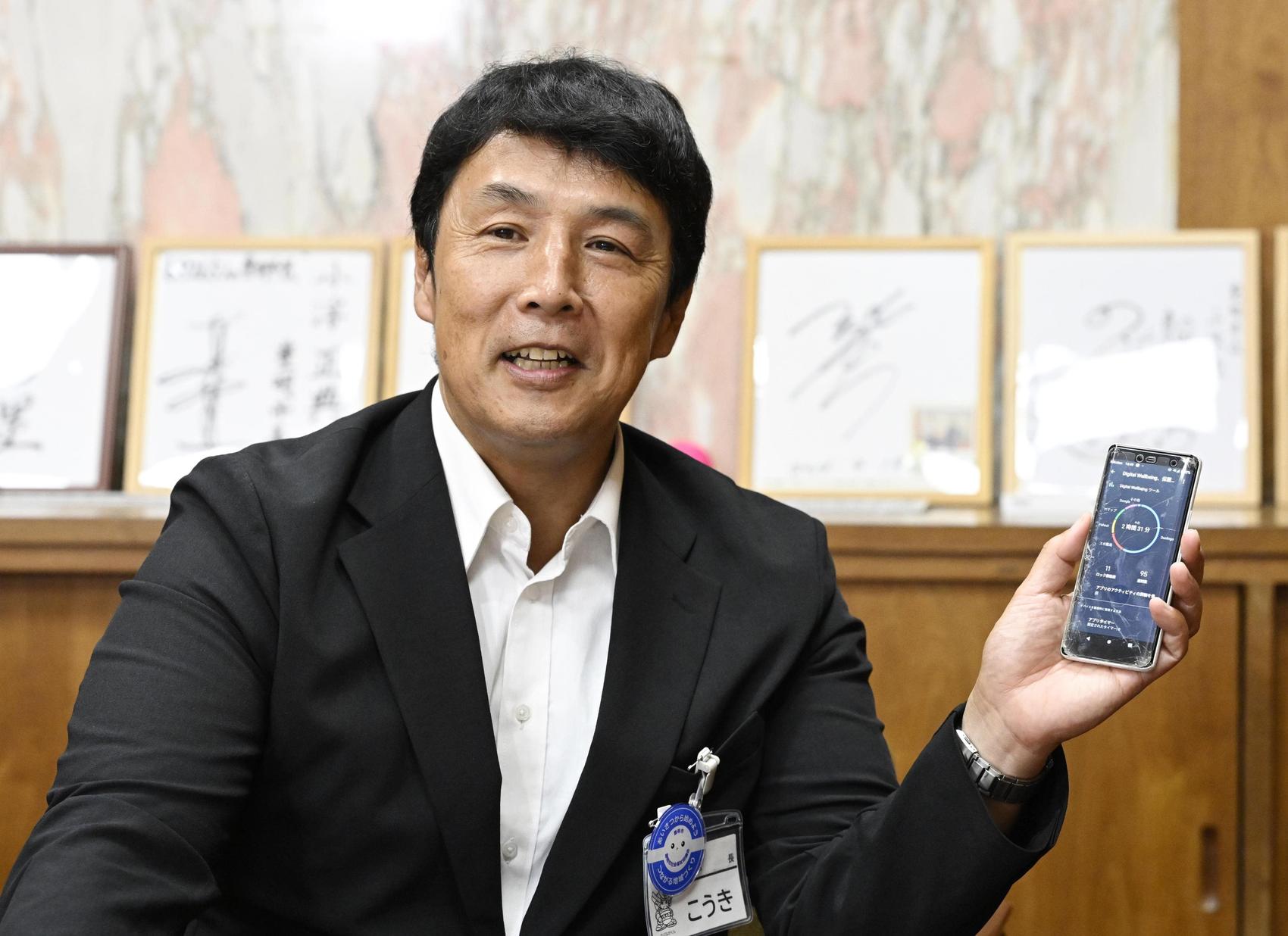

Toyoake Mayor Masafumi Koki does not see smartphones as the enemy. He uses one himself to track baseball games and check maps for work.

But after seeing children’s sleep vanish and families lose time to glowing screens, he decided that the commuter city near Nagoya needed a gentle reminder: maybe two hours a day is enough.

On Wednesday, Toyoake will put into effect a new ordinance urging residents to limit their personal smartphone use to two hours a day. The guideline does not apply to work or study, but ever since it was announced in late August, the “two-hour rule” has spread across social media like wildfire, drawing both praise and fierce criticism.

Koki knew the number would raise eyebrows. “The figure of two hours took on a life of its own,” he told Kyodo News in a recent interview. “People thought we were trying to impose a strict time limit. That’s not the case at all.”

Still, critics lined up. Entrepreneur Takafumi Horie, known for his sharp tongue online, mocked the idea publicly. Others complained that the government had no business telling people how to use their free time.

But Koki shrugs off the backlash. For him, the ordinance is not about punishment, it’s about sparking reflection. “If someone hears two hours, they’ll stop and think about how long they really use their smartphone. That’s the point.”

The roots of the ordinance lie not in abstract theory but in the lived reality of children and families in Toyoake.

In recent years, more students in the city have stopped attending school, often spending long hours on their smartphones at home. Koki does not blame smartphones outright, but he has seen how easily they become a crutch for lonely, isolated children.

“Junior high school students are often given their own rooms and their own phones,” he says. “With nothing else to do, they spend hours staring at screens. Day turns to night, their sleep suffers, and the cycle repeats.”

Reports from the city hall deepened his concern. During infant health checkups, officials noticed mothers handing smartphones to babies and toddlers. The problem, Koki realized, was not limited to teens. Adults, too, were losing sleep, sacrificing face-to-face conversation, and letting devices reshape their daily rhythms.

“Smartphones are incredibly convenient,” he concedes, “but we wanted to ask people to reconsider — are they cutting into your rest? Are they hurting family communication?”

That is why the city decided to take a bold step: to write their concern into an ordinance, not to police people’s behavior but to send a message.

“If we had only put out a pamphlet or a slogan, people would have ignored it,” Koki says. “But by making it an ordinance, people took it seriously.”

The number itself — two hours — was not plucked from thin air. City officials debated how much time people realistically had for leisure after work, school and sleep.

Studies on recommended sleep for children and adults helped guide the discussion. Eventually, they settled on a symbolic number: less than two hours on weekdays.

“Of course, if you use your phone for three or even five hours, that’s fine,” Koki explains. “But giving people a target makes the conversation possible.”

And conversation, it turns out, is exactly what they got. As of Sept. 2, the city had received 155 calls and 114 emails or letters — about 30 percent supportive, 70 percent opposed.

Some argued it was ineffective without penalties. Others bristled at the idea of government meddling in personal life. Many simply said they wished the city would instead crack down on dangerous behaviors like texting while walking.

Koki does not mind the criticism. “The backlash is useful,” he says. “It means people are thinking.” He also points out that the ordinance is legally safe: unlike Kagawa Prefecture’s stricter 2020 law targeting gaming addiction, Toyoake’s carries no obligations and no penalties.

“It’s purely idealistic,” he says. “We’re not trying to control anyone.”

Even at home, the ordinance has become part of daily life. Koki admits his own screen time sometimes runs over two hours, though much of it is for work. His wife, however, has laid down her own household rule: no phones at the dinner table.

Their fourth-grade daughter used to resist putting hers down during meals, sparking family squabbles. Now, they’re trying to change that habit together. “The downside,” Koki says, “is that I can’t keep up with baseball scores during dinner!”

Despite the noise online, Koki’s goal remains simple. He doesn’t see smartphones as villains. On the contrary, he praises their usefulness in education, research and daily convenience.

But he wants Toyoake’s citizens, especially its children, to live healthier, more balanced lives.

“This is about sleep, family, and well-being,” he says. “If the ordinance makes even a few people stop and talk about their habits, then it’s working.”

And perhaps, in the quiet hours after dinner, when phones are set aside and the city slows down, that conversation is already beginning.