Back then, though, most publications didn’t list photographers’ names with wire service photos. Instead, his memorable work usually only carried an AP or Associated Press credit. “We used to say AP stood for Anonymous Photographer,” he recalled.

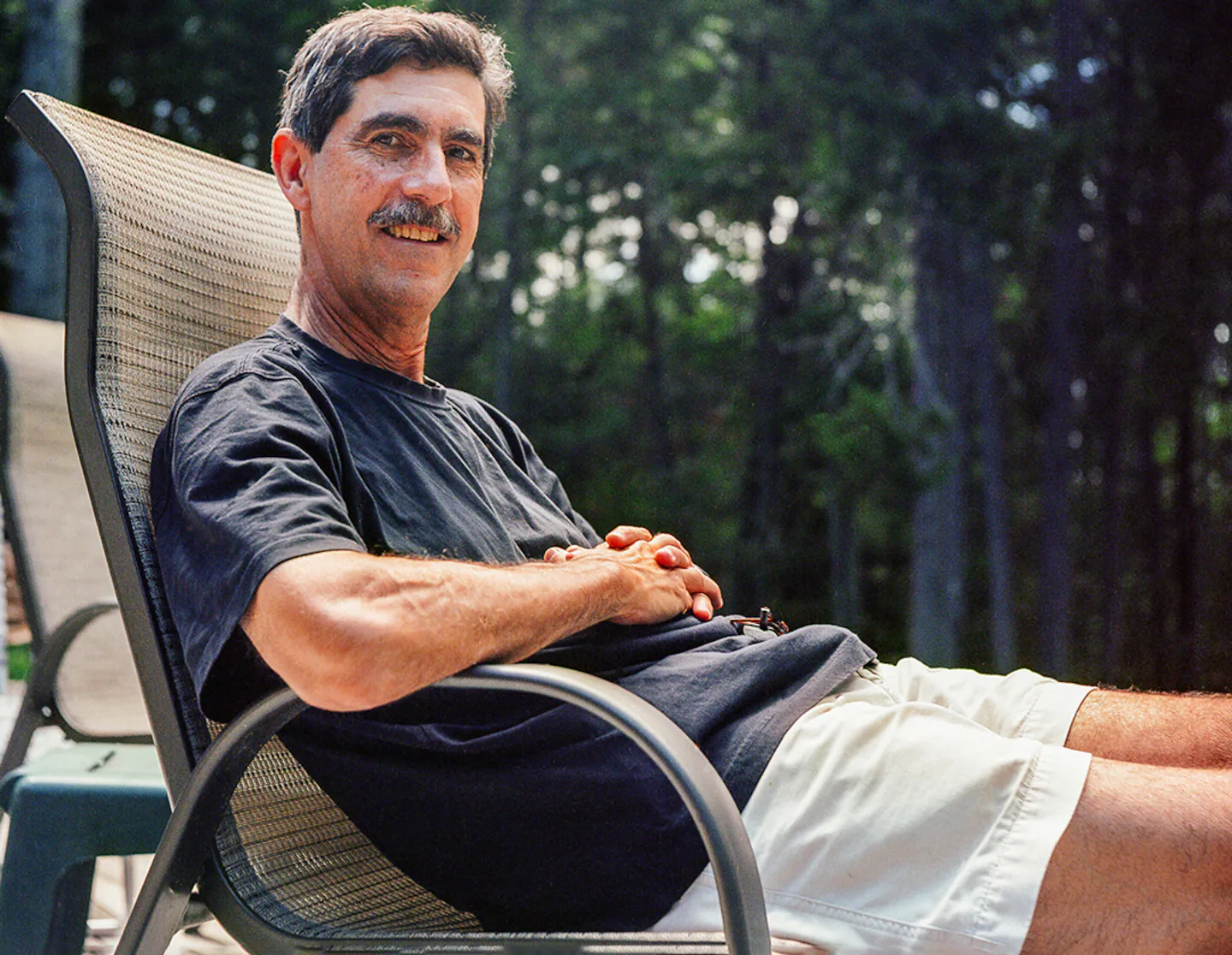

Mr. Southwick, who ran the gamut of Boston photography, from his college newspaper to the AP, The Boston Globe, and teaching at Boston University, died Sept. 15 in Care Dimensions Hospice House in Lincoln, three years after being diagnosed with cancer. He was 74 and had divided his time between his longtime home in Arlington and Boothbay, Maine.

He began his career shooting photos for The Crimson, Harvard University’s student newspaper, while he was an undergraduate.

“The cliché at Harvard was, well, you either go to Harvard or you go to the Harvard Crimson,” he said in the 2016 interview, conducted by Kristyn Ulanday Blackman, who was one of his BU students. “And for the last two years, I went to the Harvard Crimson.”

Mr. Southwick wrote occasionally, too, including a first-person account of photographing a 1973 Boston concert by 1950s revival band Sha Na Na that ended violently when audience members threw beer cans at the performers. The opening act was memorable, too. “The warm-up group, Aerosmith, was ugly and fearsome,” Mr. Southwick wrote.

After graduating, he freelanced for publications such as Time, Newsweek, and Boston magazines, and was a photographer and photo editor at The Real Paper, an alternative weekly in Boston.

Mr. Southwick went on to a staff photographer gig at the Boston Herald American before landing in 1980 at the Associated Press, where he had to up his game. Editors reminded photographers that if “you miss the picture, the world misses the picture,” he said in the interview.

“You want some pressure? You have to produce, you have to be better than everybody else — that’s it,” he added. “Our motto was: more, better, faster. Do things as fast as humanly possible — and then do them a little faster than that.”

Along with those demands was his ambition to shoot memorable photos. The New York Times published an image he captured of Caroline Kennedy outside the church on her wedding day.

He also caught St. Louis Cardinals shortstop Ozzie Smith seemingly floating in midair, upside down in one of his famous backflips.

Mr. Southwick received more than a dozen awards for his photography from the Boston and National press photographers’ associations.

“It’s tremendously high pressure, but so much fun and excitement for me, being in the middle of top stories every day,” he said. “And also the idea of, my pictures are on the front page — not just in this country, but potentially around the world.”

Peter Alfred Southwick was born March 19, 1951, in Washington, D.C.

His father had been a photographer in the Navy and had a darkroom in the basement of the family home. Mr. Southwick was 9 when he started taking photos and was serious about it by the time he was a teenager.

“It was important to him that what he was doing was going to make a difference,” said his wife, Jean Rosenberg, a retired educator. “He needed to tell that story in the image.”

Tom Frail, a longtime friend and former roommate from the late 1970s who became a newspaper and magazine editor, said that listening to Mr. Southwick “talk about what he was looking for when he was taking a photograph, and how to get the photograph into print, was a huge education for me. He would always ask, ‘What would a decent person do in this situation?’ ”

Mr. Southwick “was one of those people who had a very strong moral compass that never cracked throughout his life,” said Ty Cobb, a friend since Harvard who is now a prominent Washington, D.C., attorney and a former White House special counsel during the first Trump administration.

For nine years, beginning at the end of 1990, Mr. Southwick worked at the Globe, first as a picture editor, and then as director of photography.

He and Rosenberg had married in 1982 and had two children — Natalie, who now lives in Brooklyn, N.Y., and Lindsay of Somerville.

A self-described “unabashed homebody,” Mr. Southwick left the Associated Press, where shooting photos meant lots of travel, and took a Globe desk job largely to spend more time with his children.

“I did not like being away from them at all,” he said, adding that “my family absolutely is the most important thing in the universe to me.”

As a father, “he was interested in what I was doing, he was interested in what I thought about things, he was interested in me as a person,” Natalie said. “There was never a point in my life where I doubted if my dad loved me.”

In addition to his wife and two children, Mr. Southwick leaves a brother, Tom of Bordeaux, France, and a sister, Linda Hedio of Danvers.

A memorial service will be held at 2 p.m. Oct. 25 in First Parish Unitarian Universalist Church in Arlington.

In 2002, Mr. Southwick began teaching at BU, where he became an associate professor and directed the photojournalism program before retiring in 2017.

“His influence is ever present,” said Ulanday Blackman, his former student.

“He had strongly held convictions and believed in the power of storytelling and journalism, and how it could open up other people’s lives,” she said. “What I took away was the importance of truth and being ethical. That was an invaluable education.”

In Maine, Mr. Southwick became involved with The Opera House at Boothbay Harbor, serving on its board and taking photos of performers.

Some of his favorite works are on display there in the exhibit “Where I’ve Been, What I’ve Seen.”

Years ago, he also launched the Route 27 South project in which he melded still photos with audio recordings of his interviews with nearly 20 residents along that Maine road, from fishermen and musicians to a woman who cooked school lunches for decades in Southport.

The project was shown a few days after Mr. Southwick died, said Cathy Sherrill, executive director of the nonprofit Opera House.

“People didn’t know he died. They were coming to see it and pay tribute to him, and it was announced there,” she said of the full, standing room audience. “It was an absolute love letter to the community and preserved, for all time, a slice of life.”

Writing in The Crimson years ago, Mr. Southwick had described his photos as “just images, moments that are frozen to be recalled, to bring back the sensual thrill of the there and then. They are fragments of a timespan to which goodbye is, finally, being said.”