By Zoë Huxford

Copyright newstatesman

When Coldplay announced that they would not tour their 2019 album Everyday Life until they could make live shows “actively beneficial” to the environment, fans were sceptical. However admirable the band’s eco-consciousness, banning plastic and asking attendees to bring refillable water bottles seemed unlikely to negate the carbon emissions of a world tour.

It was not long afterwards that Taylor Swift faced severe criticism for her environmental impact. In 2022, a report named her the year’s biggest celebrity CO2 polluter from private-jet use. Her aircraft had logged over 170 flights in seven months. A representative said the plane was “loaned out regularly”, but that proved a thin defence against claims that Swift was responsible for more than 8,000 tonnes of carbon emissions in that year.

By 2024, Coldplay had reduced their tour’s carbon footprint by 59 per cent compared with previous tours. They had used a unique battery system powered by renewable sources, including solar panels and kinetic floors that convert the energy from fans’ dancing into electricity, and had offset unavoidable emissions through tree-planting. The optics were clear: while some artists were willing to trade their sense of environmental stewardship for expediency, Coldplay were not.

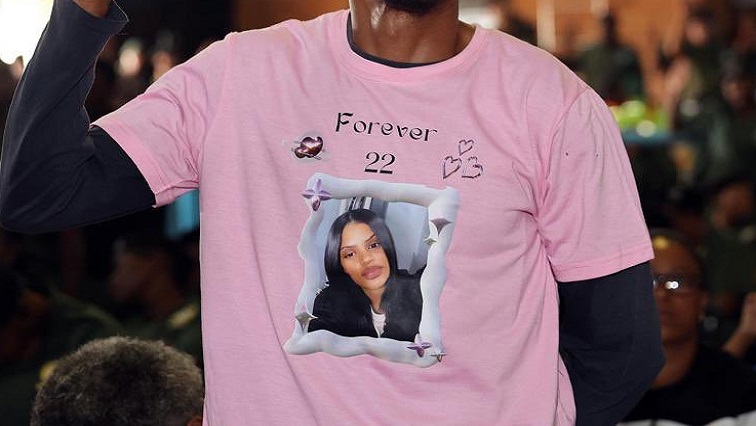

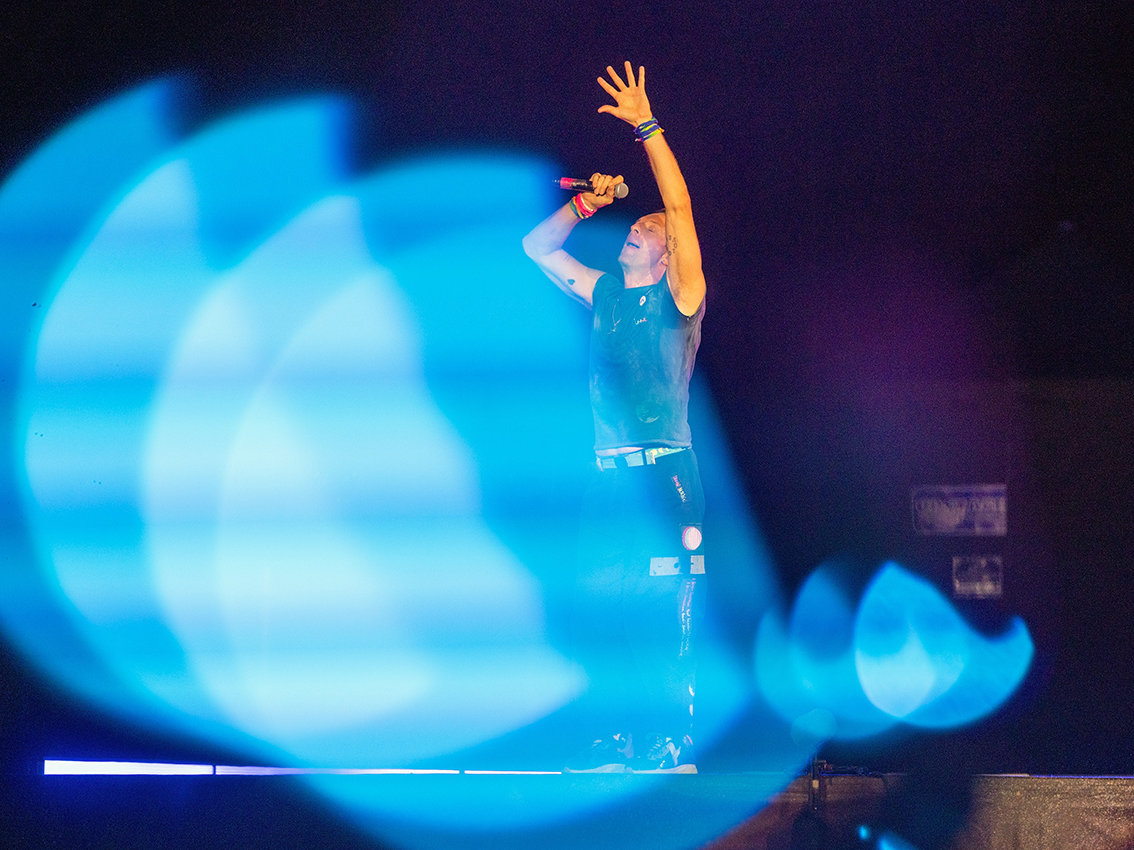

Whether a reduction in emissions constitutes being “actively beneficial” to the environment is debatable, but regardless, Coldplay’s climate guilt had been assuaged. So much so that their frontman, Chris Martin, announced earlier this month that they will extend their current tour, Music of the Spheres, by a further 138 concerts in 2027. Not bad for an environmentally concerned group.

This tour is already the most attended ever. It began in 2022 and has so far grossed £1.4bn from 13 million attendees. The new dates extend it to a 349-show global marathon. With so many stadium shows left, it could easily become the highest-earning tour of all time too, leisurely leapfrogging the current benchmark of $2.1bn, set by Swift’s Eras tour last year. Coldplay have also now played more Wembley gigs during a single tour than any other, eclipsing Swift once more. In doing so, the band has challenged some of the metrics by which musical success is measured.

What Coldplay have achieved is no small feat. Tour records have become a sort of prestige arms race, with artists collecting stats like most people do fridge magnets: highest revenue, most nights at Madison Square Gardens, greatest seismic activity. Of course, the media has played its part too, churning out headlines and feeding data into a scoreboard that fans and industry insiders follow fervently. But the carbon-neutral ambitions can now be a part of that narrative. While contradictions are blatant – flying private jets across continents does dull the halo effect – it is perhaps the most ambitious attempt yet to reframe the megatour as not only essential, but ethically possible. —

In this arena, Coldplay’s achievement is more than just commercial. It’s existential. If Swift’s Eras tour was a carefully choreographed, career-spanning retrospective laced with cultural capital – a three-hour pop-theatre event in sequins and self-mythology – Music of the Spheres is something different: a slow-burning affirmation of Coldplay’s place in the pop firmament. Less maximalist than Swift’s production but just as immersive, it is a sort of emotional infrastructure project, each night lit by promises of reforestation and reduced emissions.

Herein lies the band’s most unlikely triumph: not just commercial redemption, but cultural vindication. Coldplay have been mocked for their eager wholesomeness. Lately though, all that had felt so familiar about the band has started to feel strangely radical. A friend who saw them play their headline gig on the Pyramid Stage at Glastonbury in 2024, the band’s fifth time doing so, remarked, “I know it’s lame to sing “Fix You” in a field full of strangers, but it just feels so good.” In a music landscape increasingly defined by cynicism, irony and algorithmic precision, Coldplay’s earnest commitment – to joy, environmentalism, trying – now reads as its own kind of cringe-yet-endearing defiance.

And yet, even as Music of the Spheres becomes a logistical behemoth, it retains a surprising intimacy. There’s a kind of soft power in Coldplay’s live shows: thousands of people bathed in pastel light, singing “Yellow” with something close to reverence. It is deeply uncool. It is also profoundly affecting.

This is Coldplay’s real victory. Not the tour tally or the decarbonisation pledges. It’s the slow, patient cultivation of collective feeling, the kind of mass emotionality that pop used to aim for before it got lost in viral hooks and TikTok metrics. In 2025, Coldplay are still chasing connection; implausibly, they may be winning. In 1998, Martin said that by 2002, they would “be known all over the world”. Twenty-five years on and that is certainly true. Now, it might just be for the right reasons.

[See also: We must fight the deepfake future]