It’s no good trying to sugarcoat the troubled history of the United Nations. This paradoxical organization emerged from the ruined cities and gas chambers of World War II with the explicit goal of making sure that no destructive conflict on that scale would ever happen again. It succeeded, at the very least, in damping down the Cold War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union enough that it never escalated into civilization-ending apocalypse. How much the U.N. has really accomplished in subsequent decades to manage a world of constant disorder, worsening inequality and impending ecological collapse is very much open to doubt. It began as an unstable blend of wildly ambitious idealism, great-power cynicism and mind-numbing bureaucracy, and that combination has defined it ever since.

Any honest effort to reckon with Donald Trump’s astonishing speech to the U.N. General Assembly last week — probably the longest speech ever delivered by a U.S. president in that forum, and without question the most unhinged — requires facing a difficult truth. Beneath Trump’s wild fantasies and fabrications, and beneath all his overtly hateful and approximately fascist rhetoric, he had a point, or perhaps half a point. It was so deeply buried under the torrent of Trumpian insults and invective, and so badly obscured by an epoch-shifting moment of American self-humiliation on the global stage, as barely to be discernible. But it was still a point.

Trump accused the U.N. of “not even coming close to living up” to its global mission, and mocked it for writing “really strongly worded” letters full of “empty words” that do nothing to resolve international conflict. You could almost hear international observers gritting their teeth and nodding along: No lies detected! But if most of them agreed with that diagnosis, virtually none of them want any part of the Trumpian remedy, which seems to involve closing all international borders, repelling or expelling migrants from all European or “Christian” countries (i.e., the ones with largely white populations), ending all efforts to manage climate change and returning to an economy based on all fossil fuels, all the time.

None of that is realistic on a global scale, or especially likely to happen, and as so-called policy it’s also internally incoherent. Immigration is, without a doubt, a dangerous wedge issue that threatens the future of almost every Western-style democracy, and that Trump and other illiberal or anti-democratic leaders are eager to exploit. Climate denialism, on the other hand, is not. That obsession is largely confined to right-wing troglodytes in the U.S. (and their off-brand offshoots in other Anglophone countries). Far-right parties in Europe, in fact, exploit the climate crisis and other environmental issues as reasons to crack down on immigration; the ongoing energy transition to electric vehicles, wind farms, solar arrays and so on is not especially controversial.

But the Fourth Reich-scale ambition of this apparent Trumpian agenda is genuinely breathtaking, partly because it’s so completely untethered to political pragmatism. As for the long-term consequences of such a dramatic reversal — or implosion or willful destruction — in America’s relationship to the rest of the world, they are scarcely imaginable.

The Fourth Reich-scale ambition of this apparent Trumpian agenda is genuinely breathtaking, and the long-term consequences of this dramatic reversal of America’s relationship to the rest of the world are scarcely imaginable.

There’s a curious, and definitely not coincidental, parallel at work here: We also need to be honest about the conditions that produced the Trump phenomenon in the first place. Broadly speaking, MAGA voters in the U.S. perceived that democracy had become paralyzed by partisan division and widespread corruption; that elected representatives listened to corporate donors and entrenched elite interests but not to ordinary people; and that they were being ignored, condescended to, sneered at and left behind. They were right about all of that. Their response, depending on which Trump supporters you talk to and whether you believe what they say, was either delusional, cynical, profoundly nihilistic or downright suicidal. All those terms fit the Trump regime’s newly-hatched anti-global agenda as well.

American presidents have delivered more than 50 speeches before the U.N. General Assembly. (There is archival disagreement over what counts as an official address and what doesn’t; Google’s AI provided a “comprehensive list” that wasn’t even close to accurate.) What was once a rare and special event has become an annual ritual: From Harry Truman through Jimmy Carter, no president addressed the UNGA more than twice. But starting with Ronald Reagan, the White House incumbent has shown up at the curved edifice on First Avenue to bloviate, shutting down Manhattan traffic for a full day, almost every September.

Those 50-plus presidential addresses have been all over the map in terms of expressed ideology and historical value. If we can’t afford to whitewash the complicated history of the U.N., we also shouldn’t pretend that the previous 13 non-Trump presidents represent a legacy of unified purpose or noble intentions. Quite a few of these speeches have aged remarkably poorly, including George W. Bush’s early 2000s anti-Iraq warmongering and his blithe 2008 assertion that “Afghanistan and Iraq have been transformed from regimes that actively sponsored terror to democracies that fight terror.” A decade earlier, in 1991, his father, George H.W. Bush, had proclaimed the birth of a “new world order,” and the less said about that ignominious phrase, the better.

It’s acutely painful to read Bill Clinton’s long-winded paeans to the triumph of neoliberalism and the dawn of an era that will “reap the benefits of free markets without abandoning the social contract and its concern for the common good,” but that also required seizing “the opportunity to turn back the clock on greenhouse gas emissions so that we can leave a healthy planet to our children.” (That speech, dear reader, was delivered 28 years ago.)

If we’re eager to indict these former presidents in retrospect for their disastrous missteps and miscalculations, their areas of obvious moral blindness or their self-serving fictions about the U.S. as a global defender of “human rights” and “democracy,” we should also appreciate that, without exception, all of them understood the context and tried to seize the moment. Several presidents gave their most important speeches from the U.N. podium, knowing that the whole world was quite literally watching. What Trump said and did last Tuesday must be viewed in that light as well.

Dwight Eisenhower’s “Atoms for Peace” speech in 1953, at one of the darkest periods of the Cold War, laid out a plan for global cooperation on nuclear power that led to the creation of the International Atomic Energy Agency. John F. Kennedy’s 1963 address, delivered shortly after the resolution of the Cuban missile crisis and two months before his own assassination, celebrated the signing of the first nuclear test-ban treaty and “a pause in the Cold War,” called for an end to apartheid in South Africa and discrimination in the American South, and proposed a joint U.S.-Soviet mission to the moon.

Reagan’s early-’80s U.N. speeches were heavy on anti-Communist rhetoric about the importance of free markets and individual rights, and often cited the perceived crimes of Marxist-Leninist regimes. But it’s fair to say that Reagan never indulged in outright name-calling or hateful invective, stressed his desire for negotiation over confrontation and left the nuclear saber-rattling to subordinates. That allowed him to make headlines in 1986 with one of the most remarkable speeches in U.N. history, when he discussed his first private meeting with Mikhail Gorbachev and the first steps toward nuclear disarmament:

For over 15 hours Soviet and American delegations met; for about five hours General Secretary Gorbachev and I talked, alone. Our talks were frank. The talks were also productive — in a larger sense than even the documents that were agreed. Mr. Gorbachev was blunt, and so was I. We came to realize again the truth of the statement: Nations do not mistrust each other because they are armed; they are armed because they mistrust each other.

Indeed, the overarching theme of presidential addresses to the U.N., expressed many times in many different ways — most clearly in memorable speeches by Eisenhower, Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, the senior Bush and Barack Obama — has been an appeal to a global sense of shared responsibility and collective destiny. The world is supposed to work together through this flawed institution, they all told us, to fight hunger and disease, to spread “democracy” and “freedom” (even if those terms remained ambiguous or undefined), to eliminate the most dangerous kinds of weapons and reduce the risk of nuclear Armageddon.

Several presidents have given their most important speeches from the U.N. podium, knowing that the whole world was quite literally watching. What Trump said and did last Tuesday must be viewed in that light as well.

Amid whatever contentious points they wanted to score, presidents have nearly always reverted to some broad-minded but nonspecific celebration of diversity and pluralism. As one president told the General Assembly a few years back, the U.N. was a “beautiful constellation of nations, each very special, each very unique, and each shining brightly in its part of the world,” and each person gathered in the auditorium was “the emissary of a distinct culture, a rich history, and a people bound together by ties of memory, tradition and the values that make our homelands like nowhere else on Earth.”

Have I telegraphed the punchline? That was Donald Trump in 2018, in a speech that also announced an incoherent trade policy based on unilateral tariffs and proclaimed that the U.S. had withdrawn from the U.N. human rights council and would not recognize the International Criminal Court: “America is governed by Americans. We reject the ideology of globalism, and we embrace the doctrine of patriotism.”

Halfway through his first term, Trump and his handlers still felt constrained by the conventions of international discourse. The full-on MAGA agenda was just visible in embryonic form, like the larval xenomorph of “Alien” when it’s still inside your chest.

You’ve probably read more than enough about Trump’s General Assembly speech last week, which lasted nearly an hour was received by nearly everyone listening with a mixture of dread and disbelief. But perhaps it was illuminating, as this entire endless year has been illuminating. We now see the true agenda of the Trump presidency, whoever actually crafted it and wherever it may lead, freed from its chrysalis. It’s a massive overreach for global power and influence, at a moment when he is widely despised virtually everywhere, and a complete rejection of the entire legacy of post-World War II internationalism. That wasn’t just unlike any other American president’s speech; it was categorically different from any other speech ever delivered in that building or to that audience.

Want more sharp takes on politics? Sign up for our free newsletter, Standing Room Only by Amanda Marcotte, also a weekly show on YouTube or wherever you get your podcasts.

Climate change is “the greatest con job ever perpetrated on the world,” democracy and human rights are woke fictions that have allowed “uncontrolled migration” by “a force of illegal aliens,” the only persecuted minority of any consequence are Christians. (He didn’t actually say white Christians; he didn’t have to.) “Your countries are going to hell,” he told the leaders of Europe’s liberal democracies. “You want to be politically correct and you are destroying your heritage.”

If pro-Nazi aviator Charles Lindbergh —a Trump-style celebrity of an earlier day — had actually been elected president in 1940, as he is in Philip Roth’s 2005 novel “The Plot Against America,” he could hardly have outdone that in overtly racist and xenophobic paranoia, or in proclaiming America as an isolationist fortress of embattled white pride. It’s beyond hilarious for the Trump regime to pose as defenders of “culture” or “civilization” by anyone’s definition, but I’m afraid they’re not kidding.

Trump really does want to be dictator for life, and very likely his circle of enablers think that’s the clearest pathway to ditching democracy. That’s the only conclusion I can draw. His real audience last week was not the assembled world leaders. He doesn’t care what they think and is righteously angry that they won’t bend to his whims quite as readily as university presidents and elite law firms do. He was talking to the true believers at home who might yet, he thinks, be willing to fight for that beautiful dream.

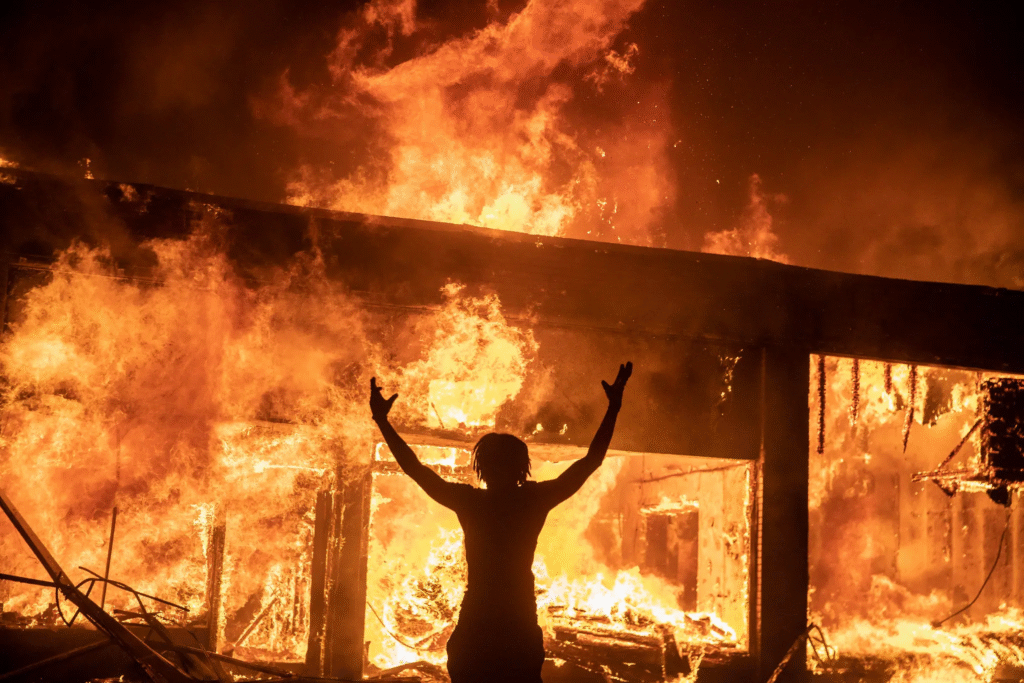

I guess we’ll find out. If other countries conclude after that speech that they’re better off doing business with Xi Jinping while America “does its own research” and sets itself on fire, can you really blame them?