By Eric Szeto,Ivan Angelovski,Jordan Pearson

Copyright cbc

Members of Russia’s business elite are flying in Canadian-made luxury planes that were imported after sanctions targeting the country’s aviation sector came into place, CBC’s visual investigations unit has found.

Russian import records obtained by CBC News show 34 business jets and commercial aircraft built in Canada and sold on the secondary market have ended up in Russia since it invaded Ukraine in February 2022.

Those records, as well as flight data, aviation industry documents and leaked border-crossing information, reveal that sanctioned oligarch Igor Kesaev imported a Bombardier business jet in July 2023. Another jet arrived in March 2024 via a company majority-owned by another oligarch, Sergey Shishkarev, an ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Other jets were imported by Russian airlines that cater to charter flights.

Many Western observers say these aircraft end up there through loopholes that allow importers to evade sanctions by shipping the planes through countries friendly to Russia, such as Oman and Kyrgyzstan.

“It’s quite clear that Russia has been able to work around some of these sanctions in the classic black market model, but with 21st-century sophistication,” said Fen Hampson, a professor of international affairs at Carleton University in Ottawa. “They are buying parts, even entire aircraft jets, through middlemen in countries that don’t honour Western sanctions.”

Hampson described it as “big business,” adding that “not a whole lot” has been done to slow down or stop these transactions.

Kesaev’s lawyer, Roeland Moeyersons from the Belgium-based EU-Sanctions law firm, wrote in an email: “Mr. Kesaev declines to comment on press articles. I trust you understand.”

CBC reached out to Shishkarev’s Delo Group but did not receive a response.

Bombardier declined to comment on specific aircraft because they were sold on the secondary market without the company’s involvement and said it complied with sanctions.

Immediately after Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, international sanctions were placed on the export of aircraft and parts into the country by the EU, U.S. and Canada.

Russia’s air industry, a majority of which is made up of Western aircraft, has been severely affected by sanctions, but more than $1 billion worth of aircraft and parts have still reportedly been imported into the country.

In February, the U.S. Department of Justice arrested three people for allegedly operating a scheme to illegally export aircraft parts and components from the U.S. to Russia. Two months earlier, a dual U.S.-Russian citizen was indicted for allegedly attempting to export aircraft through Armenia to Russia.

Australia to Moscow, via Oman

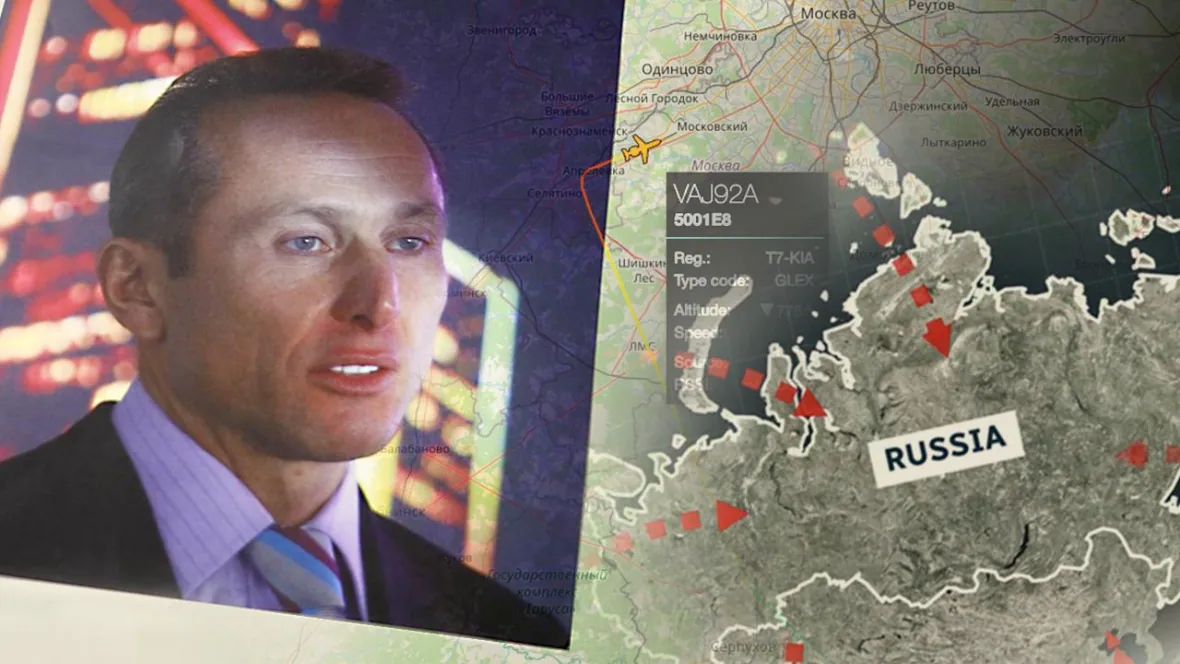

According to records shared with CBC News by U.S. trade data company Import Genius, a Bombardier Global Express business jet was imported into Russia by Delo Group, a major Russian trade and logistics company that is majority-owned by Shishkarev, a former politician and billionaire who has been praised by Putin.

On Feb. 8, 2024, according to flight records, the plane flew from Perth, Australia, to Oman before switching to Russian registration and flying to Moscow. The plane was imported on March 30, 2024, from Oman by Delo Group.

Oman has in recent years become a hot spot for ship-to-ship transfers of Russian oil heading for India, and part of a network of transhipping countries including Turkey, Belarus and Armenia that re-export goods to Russia after importation.

“We have to be honest and acknowledge that the Russian government has found a number of willing partners in Western countries as well as in other countries in the same region as Russia that have helped them to evade sanctions,” said Matthew Light, an associate professor of criminology at the University of Toronto.

According to Swiss-based CH-Aviation, an aviation industry intelligence platform, the Delo plane was owned by the Bank of Utah in a trustee arrangement. The bank deregistered the plane from the U.S. on Feb. 9, 2024, and said it was being exported to Oman.

The Bank of Utah did not respond to a request for comment, but says in its FAQ for aircraft owner trusts that it “does not do business with sanctioned entities.”

Oligarch who supplied Putin’s army flies Canadian

The records reviewed by CBC’s visual investigations unit showed that some aircraft imported into Russia were by companies that focus on luxury private charters for the country’s elite.

Of the dozens of trade records reviewed by CBC, only one import to Russia had an individual’s name directly attached: Igor Albertovich Kesaev — for a black Bombardier business jet.

Kesaev is a Russian oligarch who is worth $4.5 billion US, according to Forbes. He is the owner and chairman of Mercury Group, which owns Megapolis Group, the leading tobacco distributor in Russia.

He was also the main shareholder of a company invested in the Degtyarev weapons factory, which supplies the Russian armed forces. He also has links to Russia’s security forces via his Monolith Foundation, which provides financial assistance to retired personnel and is staffed by former security officers.

Kesaev was sanctioned by the European Union in 2022 because his business activities provided “a substantial source of revenue for the government of the Russian Federation, which is responsible for the annexation of Crimea and the destabilization of Ukraine,” according to the EU. He’s also been sanctioned by the U.S. and Canada.

The jet was imported on July 10, 2023, according to records.

“Russian elites are still travelling on their private jets,” said Hampson. “Sanctions at the best of times in a world of nation states are a bit like a sieve…. And the Russian oligarchs obviously, as long as they’re in favour with Vladimir Putin and his regime, they can act with impunity.”

Shadowy network

Aviation records provided by CH-Aviation, along with plane registration records obtained by CBC News, show that the plane imported by Kesaev was manufactured by Bombardier in Toronto in 2009 before being sold to Global Air Services Limited in 2010 for export to Bermuda.

According to documents provided to CBC by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), one of Bermuda-based Global Air Services Limited’s directors at the time was Christodoulos G. Vassiliades, a Cypriot lawyer under sanctions for being a “prolific enabler” of Russian oligarchs.

Vassiliades is also listed as the president of Kesaev’s Bermuda company G IV-SP Air Service Ltd. in the ICIJ documents.

When reached for comment, Vassiliades responded that he had resigned from directorship of “all companies as of [April 4, 2023], including Global Air Services Limited,” and did not address questions around Kesaev’s jet.

The plane was operated by U.K.-based Gamma Aviation with a Bermuda registration — VQ-BKI — until 2020, at which point it switched registration again and was operated by Austria-based Avcon Jet, at its local office Avcon Jet San Marino, as T7-KIA.

San Marino, a microstate surrounded by Italy, isn’t part of the EU and has historically been friendly to Russia — even buying Russia’s Sputnik COVID-19 vaccine — although it joined Western countries in sanctioning Russia in March 2022.

According to flight records, the last time the plane was in Europe was on Feb. 19, 2022. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was imminent, and the West had been threatening sanctions for weeks. On that day, the jet flew from Milan, Italy, to Moscow under Avcon’s operation.

It’s unclear who was operating the plane after that.

Documents from CH-Aviation state that until Feb. 27, 2022, two days after European aviation sanctions were announced, Avcon was listed as the operator of the plane as it travelled between Moscow and the Maldives on Feb. 25 and 27.

Data from flight tracking company ADS-B Exchange also lists the plane’s operator code during those flights as starting with “VAJ,” which according to Eurocontrol belongs to Avcon Jet San Marino. These codes may be stored on the plane’s onboard computers even after an operator change.

Avcon Jet San Marino disputed that it was operating the plane after European sanctions came into force and said that it had been “the service provider for the aircraft T7-KIA in the past, however all services were terminated immediately following the publications of sanctions.”

“No flights have been performed under our service agreement since Feb. 22 [2022].”

The plane appears to go dark until June 2023, when it re-emerges with Russian registration just before being imported on July 10, 2023, by Kesaev, more than a year after sanctions came into force.

The shipper, according to import records, was Global Air Services Limited.

Oligarch connected to jet for years

CBC found evidence linking Kesaev to the jet years before he imported it into Russia in 2023.

A leaked database of the Russian border service provided to CBC by iStories, an independent Russian investigative journalism website, showed that on Aug. 13, 2021, Kesaev travelled from Russia to Genoa, Italy, on board a flight with the tail T7-KIA.

According to data from ADS-B Exchange flight logs, a plane with the same tail T7-KIA flew from Moscow to Genoa Cristoforo Colombo Airport in Italy on the same day.

Russian internet users have long connected Kesaev to the plane. A 2017 Instagram post from a Russian plane spotter featuring a photo of a black Bombardier jet with the tail VQ-BKI — the plane’s tail before switching to T7-KIA — reads “bombardier Igor Kesaev.” A commenter wrote: “Kesaeva is global.” In another Instagram post of the plane from 2018, the caption reads “Kesaevsky Black Beauty.”

Last year, Kesaev applied to be removed from the EU sanctions list, claiming he had divested from his investment in the Degtyarev plant, which an EU court rejected.

Christina McCraw, a spokesperson for Bombardier, said: “Bombardier conducts its business in strict compliance with applicable laws and government-published sanctions.”

“The company has processes in place to ensure that aircraft, parts and services are not sold to sanctioned parties.”

De Havilland Canada, which also had planes on the Russian import list, said that its aircraft were sold on the secondary market and were in Russia before the start of the war, after which they were effectively seized and re-registered in the country.

Neil Sweeney, vice-president of corporate affairs for De Havilland Canada, said: “De Havilland Canada is aware of and abides by the international sanctions placed by Canada. Since sanctions were introduced, we have sold neither parts nor aircraft to Russia.”

Both Bombardier and De Havilland said they comply with government-issued sanctions.

Do you have any tips on this story? Please contact Eric Szeto: eric.szeto@cbc.ca