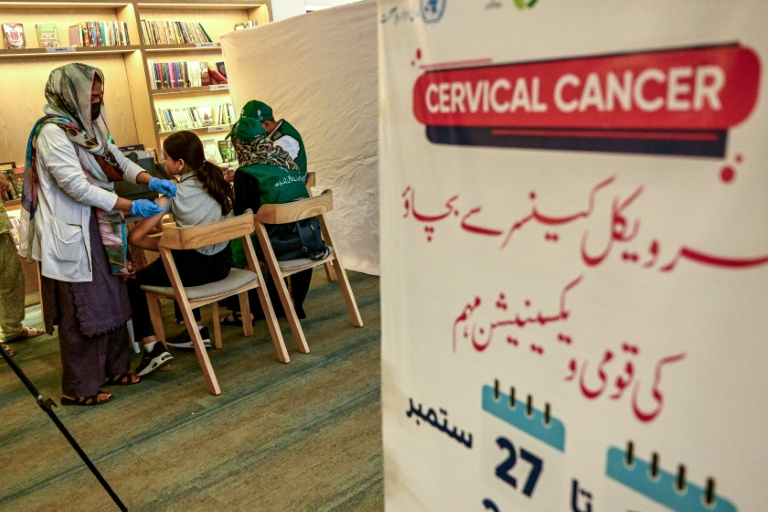

Misinformation plagued the first rollout of a vaccine to protect Pakistani girls against cervical cancer, with parents slamming their doors on healthcare workers and some schools shutting for days over false claims it causes infertility.

The country’s first HPV vaccine campaign aimed to administer jabs to 11 million girls — but by the time it ended Saturday only around half the intended doses were administered.

A long-standing conspiracy theory that Western-produced vaccines are used to curb the Muslim population has been circulating online in Pakistan.

Misinformation has also spread that the vaccine disrupts the hormones of young girls and encourages sexual activity, in a country where sex before marriage is forbidden.

“Some people have refused, closed their gates on us, and even hid information about their daughter’s age,” vaccinator Ambreen Zehra told AFP while going door to door in a lower-middle-income neighbourhood in Karachi.

Only around half the intended vaccines had been administered, according to a federal health department official who spoke to AFP on condition of anonymity.

“Many girls we aimed to reach are still unvaccinated, but we are committed to ensuring the vaccine remains available even after the campaign concludes so that more women and girls get vaccinated,” they said on Friday.

One teacher told AFP on condition of anonymity that not a single vaccine had been administered in her school on the outskirts of Rawalpindi because parents would not give consent, something she said other rural schools had also experienced.

A health official who asked not to be named said some private schools had resorted to closing for several days to snub vaccine workers.

“On the first day we reached 29 percent of our target, it was not good, but it was fine,” said Syeda Rashida Batool, Islamabad’s top health official who started the campaign by inoculating her daughter.

“The evening of that first day, videos started circulating online and after that it dipped. It all changed.”

A video of schoolgirls doubled over in pain after teargas wafted into their classroom during a protest several years ago was re-shared online purporting to show the after-effects of the vaccine.

The popular leader of a right-wing religious party, Rashid Mehmood Soomro, said last week the vaccine, which is voluntary, was being forced on girls by the government.

“In reality, our daughters are being made infertile,” he told a rally in Karachi.

In 95 percent of cases, cervical cancer is caused by persistent infection with Human Papillomavirus (HPV) — a virus that spreads through sexual activity, including non-penetrative sex, that affects almost everyone in their lifetime.

The HPV vaccine, approved by the World Health Organization, is a safe and science-based protection against cervical cancer and has a long history of saving lives more than 150 countries.

Cervical cancer is particularly deadly in low and middle income countries such as Pakistan, where UNICEF says around two-thirds of the 5,000 women diagnosed annually will die, although the figure is likely under-reported.

This is because of a significant lack of awareness around the disease, cultural taboos around sexual health and poor screening and treatment services.

It is underlined by the damaging belief that only women with many sexual partners can contract sexually transmitted infections.

In Europe, where the HPV vaccine has been highly effective, there were around 30,000 diagnoses across all 27 EU nations in 2020, of which around one-third of women died, according to the European Commission.

“My husband won’t allow it,” said Maryam Bibi, a 30-year-old mother in Karachi who told AFP her three daughters would not be vaccinated.

“It is being said that this vaccine will make children infertile. This will control the population.”

Humna Saleem, a 42-year-old housewife in Lahore, said she thought the vaccine was “unnecessary”.

“All cancers are terrible. Why don’t we tell our boys to be loyal to their wives instead of telling our girls to get more vaccines?” she told AFP.

Pakistan — one of only two countries along with Afghanistan where polio is endemic — remains stubbornly resistant to vaccines as a result of misinformation and conspiracy theories.

After marking one year without polio cases for the first time in 2023, the crippling disease has resurged with 27 cases reported in 2025 so far.

In response to overwhelming misinformation about the HPV vaccine, Pakistan’s minister of health, Syed Mustafa Kamal, took the bold move to have his teenage daughter vaccinated in front of television cameras.

“In my 30-year political career I have never made my family public,” he told reporters.

“But the way my daughter is dear to me, the nation’s daughters are also dear to me, so I brought her in front of the media.”